Tina Touli is a London‑based designer working across disciplines, moving fluidly between digital and print, typography, branding, motion, and 3D. Known for blending the analogue with the digital, she mixes materials and technologies in inventive ways. Her curiosity has led her to create phygital experiences, experimenting with materials, techniques, sound, and surroundings.

Tina’s way of experimenting with phygital experiences, and letting curiosity guide the process, feels very familiar to us. At Bloomerangas, one part of what we do is create phygital, gamified experiences — or Bloomerangas Playgrounds, as we call them. These experiences can live purely in the digital realm, exist as simple physical installations, or expand into fully immersive environments with multiple interactive stations, each inviting participants to explore creativity, teamwork, and self‑discovery through play.

In this talk, we explore creative expression through phygital experiences — spaces where physicality and technology meet, and where play opens the door to a more intuitive creative flow. Tina reflects on experimentation as a core design practice, how personal projects feed into client work, and how tools like AI can support — but not replace — a designer’s creative voice.

Let’s dive in.

Designing across mediums

For Tina, working across disciplines isn’t a strategic decision — it’s a necessity. “If you ask me to do the same thing again and again, I get bored,” she admits, explaining why she constantly moves between print, branding, web, motion, 3D, and installation work. Repetition, for her, doesn’t create mastery — it drains energy.

Moving between mediums keeps her engaged and curious. Each discipline feeds the next: branding informs motion, motion feeds back into typography, and digital work often sparks physical experimentation — and vice versa. Rather than seeing these fields as separate, Tina treats them as part of one continuous practice.

This way of working also reflects how she understands creativity itself. It’s not about doing everything at once, or trying to master every tool, but about allowing curiosity to lead. Switching mediums becomes a way to reset, to see ideas from a new angle, and to keep the work — and herself — creatively alive.

Creating immersive, phygital experiences

One of Tina’s most immersive projects, Voices in My Head (2025), grew out of a desire to create an experience people could physically and emotionally enter. “I wanted to create something that allows you to get lost within it,” she explains — a space where you can pause, disconnect from external noise, and turn inward. Rather than beginning with screens or software, the project started with analog experiments: liquid compositions filmed up close, producing slow, hypnotic visuals that invited viewers to linger and let their attention soften.

For Tina, this blend of physical process and digital outcome is at the heart of phygital work. The tactile experiments weren’t sketches to be replaced later — they became the foundation of the final experience, carrying a sense of materiality and imperfection into the digital realm.

Sound played an equally important role. For an immersive installation, it isn’t an add‑on but a core ingredient. For Voices in My Head, Tina collaborated with singer Lydia Scarlet, whose voice translated emotion into sound — moving between calm and intensity, softness and tension. Together, the visuals and sound formed a 20‑minute audiovisual piece designed not to guide or instruct, but to hold space for individual interpretation.

The project took physical form at Paradiso Festival as a fully immersive installation. LED flooring, surrounding screens, mirrored walls, and spatial sound transformed the work into a room visitors could step inside. Without directions or prompts, people chose how long to stay and how to engage.

Many later described the installation as a place to rest — a pause from the sensory overload of the festival, a moment to breathe. For Tina, this response affirmed what phygital experiences can offer when physical presence, digital tools, sound, and space are carefully composed: not spectacle, but embodied attention.

Exploring textures, materials, and making by hand

Tina’s process often begins far from the screen. She collects textures, materials, packaging, and found objects — storing them in what she calls her “treasure boxes.” As she puts it, “anything that stimulates our senses can be an interesting object to investigate.” What others might see as clutter becomes a personal archive of sensory triggers.

When a project begins, she returns to these materials. Sometimes a texture sparks an idea. Sometimes a photographed object becomes the seed of a typographic form. Other times, the material itself becomes the final outcome.

Analog exploration isn’t nostalgia — it’s efficiency. A ripped piece of paper can be more convincing than a digitally simulated effect. A quickly assembled paper structure can solve a concept in minutes that might take days in 3D software.

For Tina, working by hand isn’t slower. Often, it’s faster — and more alive.

Finding creative voice

This instinct to make by hand has deep roots. Growing up, Tina was surrounded by making. Her father built furniture, repaired cars, and constructed objects from scratch. She spent time beside him, handing tools, measuring materials, learning through doing.

Only later did she realize how much that environment shaped her creative instincts. Designing, measuring, cutting, assembling — these weren’t new skills, but extensions of something she had always done.

Finding a creative voice, Tina believes, often means reconnecting with what felt natural early on. “If you don’t enjoy it, you’ll never reach that level,” she says, encouraging designers to follow what genuinely excites them rather than what’s trending online. What you enjoyed as a child frequently points toward what you’ll excel at as an adult.

Rather than chasing trends or copying references, she encourages creatives to lean into what genuinely excites them.

Pushing creative boundaries with clients

Clients often arrive with references — usually pulled from Pinterest or elsewhere online. Tina sees this not as a limitation, but as a starting point.

Her approach is to propose multiple creative routes: one that aligns closely with the brief, one that gently pushes it forward, and one that challenges expectations. “It’s our responsibility as creatives to propose ideas,” Tina says — not simply recreate what already exists. This gives clients safety, direction, and room to experiment.

At the same time, she’s clear-eyed about design’s role. Design isn’t self-expression for its own sake. It exists to serve a purpose. A piece that works perfectly for a client may not belong in a portfolio — and that’s okay.

What you choose to show publicly shapes what you’ll be hired for next. Personal projects become signals. They quietly steer your career in the direction you want to grow.

Navigating AI in creative work

Tina approaches AI with curiosity and caution. “For me, it’s a shortcut in the process — not the final outcome,” she explains. Rather than using AI to generate finished visuals, she treats it as a way to extend her own thinking — feeding in her work to explore variations, accelerate repetitive tasks, and test possibilities within a language that is already hers.

In practice, this often means using AI-generated outputs as raw material. Tina redraws, traces, collages, and recombines results, reshaping them through her own hand and eye. The technology helps her move faster, but authorship remains human.

She’s also attentive to what AI tends to strip away. While results can look polished and convincing, they often lack character. When everything begins to look similar, Tina believes the designer’s role becomes even more critical — not simply to operate tools, but to bring intention, judgment, and emotional clarity into the work. Used this way, AI becomes part of the process, not the voice behind it.

Experimentation, play, and creative flow

Experimentation doesn’t happen when time magically appears. “You never really have time — you make time,” Tina says, emphasizing that personal work requires intention, commitment, and a conscious decision to prioritize exploration.

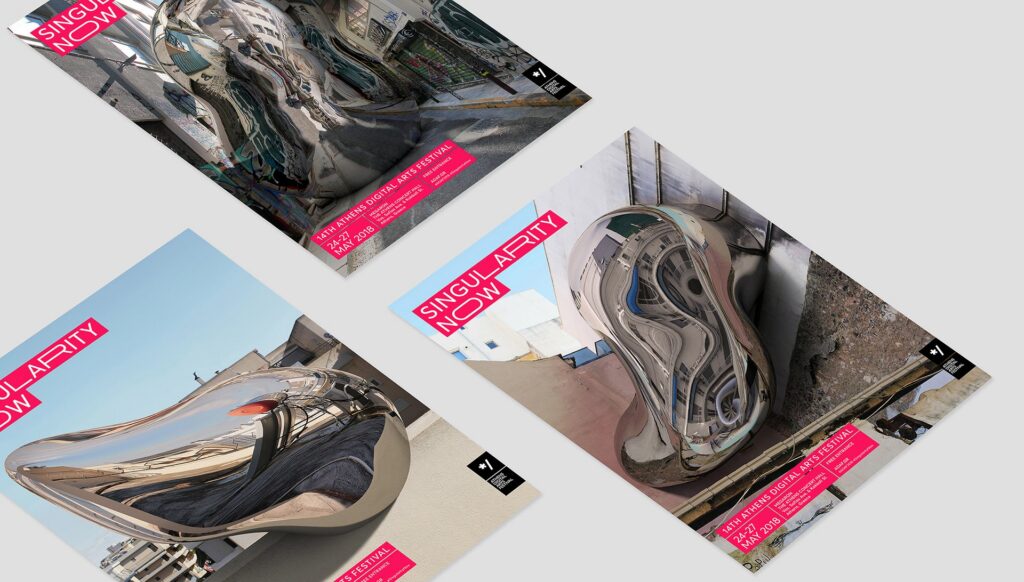

Projects designed for festivals, initiatives, or specific spaces create just enough structure to experiment freely, without the pressure of client expectations. Many experiments never see the light of day — and that’s part of the process. Each attempt trains the eye, sharpens instincts, and makes future work faster and stronger.

Across mediums, tools, and projects, play remains central to this process. “Start with what you have,” Tina encourages. “You’ll figure it out along the way.” Play allows curiosity to lead, makes room for mistakes, and keeps the work human.

Check out Tina Touli’s work: https://tinatouli.com & https://www.instagram.com/tinatouli/