Boasting a unique visual sensibility, Japanese design reflects the aesthetic prowess of the country’s storied culture. Japan itself sits at the intersection of art, creativity, exploration, and, most importantly, individuality.

Setting trends and precedent, Japanese design exists outside of the traditional constructs of the Western world providing a unique perspective that invites dialogue between disciplines, from branding and graphic design to digital, immersive experiences, and beyond.

Let’s explore how Japan’s diverse design ecosystems have and continue to influence our world’s visual culture through three of the country’s ancient concepts of Yūgen, Kanso, and Datsuzoku.

1. Yūgen (幽玄): The mystery of beauty beyond comprehension

In traditional Japanese aesthetics, Yūgen is a concept associated with depth and emotional resonance beyond the ordinary.

As one of the four concepts of Japanese beauty—the other three being Sabi (beauty of aging), Wabi (temporary and intense beauty), and Shibui (beauty in simplicity)—Yūgen embodies evocative beauty that lies beyond what can be easily seen or expressed. It refers to those rare, sublime moments in which we delve in feelings of awe, wonder and appreciation and into reflection, so powerful to put into words.

Yūgen emerged as part of a broader appreciation for life’s fleeting nature and the idea that there is a hidden or unseen dimension to this world.

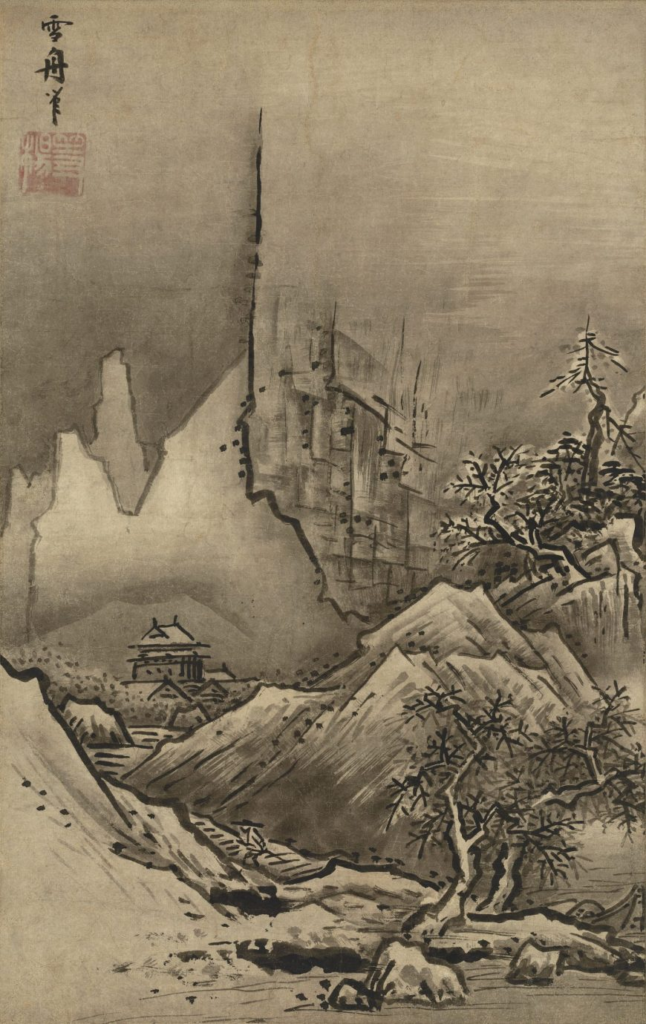

Sumi-e, Japanese ink brush painting

The spirit of Yūgen is materialized in Japanese design through a contrasting interplay of light and shadow along with an understated color palette to evoke a touch of deepness and mystery.

As such, Yūgen plays a significant role in what is left unsaid and its influence can be seen across both ancient art forms, such as sumi-e, or ink wash painting. Sumi-e is the traditional Japanese art form identifiable by its subtle monochrome gradation of black sumi ink and water on thin rice-paper.

Considered minimal strokes in a multitude of shades invite onlookers to “fill in” the empty spaces themselves in order to engage in a deeper level with the artwork. Behind these nuances is the idea of stimulating the mind towards imagined possibilities of what may lie ahead, resulting in something oftentimes far richer and more interesting than what is clearly defined.

Nature, such as birds, flowers, and animals, scenes of life in palaces and homes, as well as a wide variety of human figures, often stylized and elongated, are common sumi-e subjects.

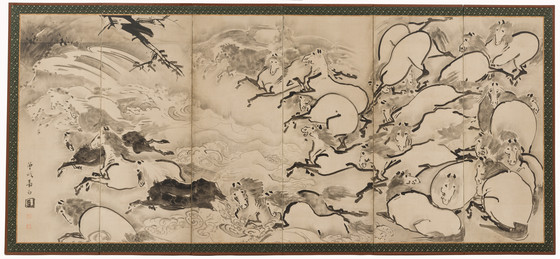

Hasegawa Tōhaku

A distinctive characteristic of Japanese culture is people’s acute awareness of the world around them. The use of natural motifs and color palettes across various disciplines, such as graphic design, landscaping, product design, and home interiors, reflects a strong connection between Japan’s love for nature and the aesthetic choices.

Hasegawa Tōhaku’s Pine Trees screen consists of two six-paneled folding screens depicting misty, Japanese pine trees in an interplay of abstraction and addition. Through minimal linework and a sparse population of pine trees as the subject matter, Tōhaku evokes a sense of cold and loneliness enhanced by empty white spaces between each tree pair.

In addition, Tōhaku illustrates the Zen Buddhist concept of Ma (間, negative space) and evoking the Japanese Wabi aesthetic (侘, appreciation of all that is imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete in nature), both still prevalent in many forms of Japanese design.

Yūgen Manga

Drawing and incorporating elements from sumi-e, Yūgen manga features a minimalist approach in its aesthetic.

What sets Yūgen manga apart is its emphasis on subtlety and emotional depth over action or drama.

Unlike other genres, Yūgen manga is defined by subtlety and restraint, emotional depth, nature and transience, and symbolism, representing a captivating intersection of art, philosophy, and storytelling.

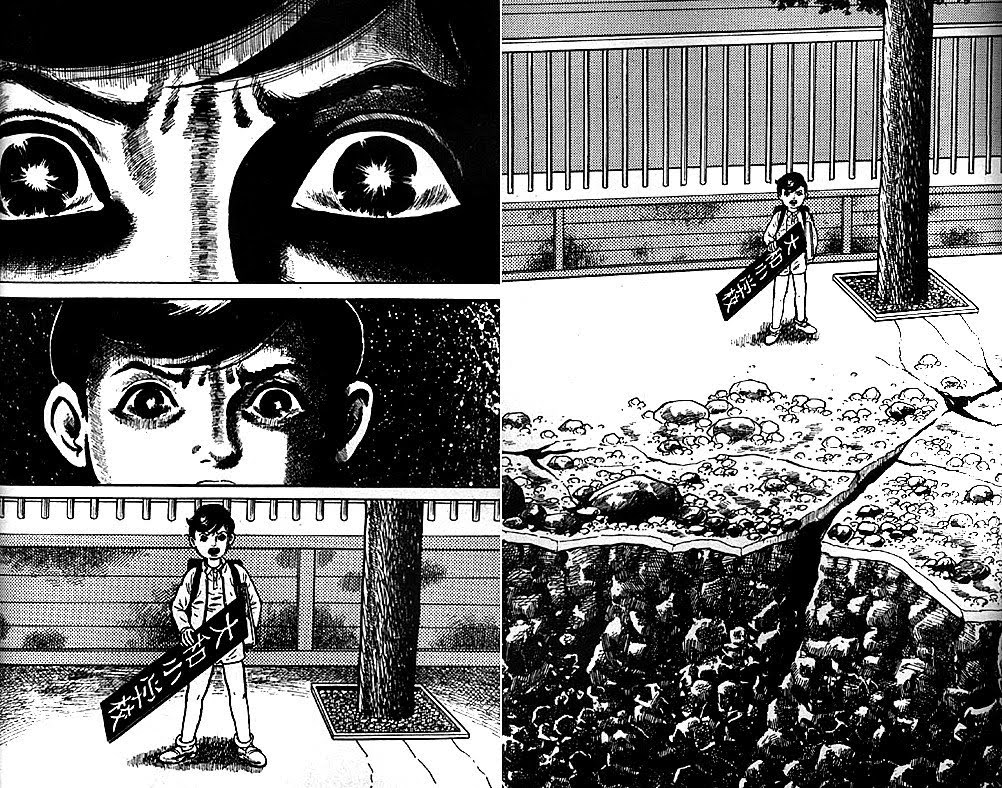

Hyōryū Kyōshitsu (The Drifting Classroom) by Kazuo Umezu

For Japanese manga artist Kazuo Umezu—also known as the “God of Horror Manga”—diving deep into the world of gore and macabre terror comes easy.

In Hyōryū Kyōshitsu, or The Drifting Classroom, Umezu presents a surreal exploration of childhood and fear in true Yūgen fashion. Inflicting fear and unease in the viewer, he uses subtle visual cues, like jagged edges, close-in-action moments, and uncomfortable aesthetics of insect-like fantasy creatures.

Umezu’s images are conceptualized in contrasting jet-black spaces, almost in conflict with considered white spaces, achieving emotional resonance with the reader.

His characteristic style uses splash pages—“panoramic” images arresting the panel-to-panel progression of the narrative that capture some major object or event—to enhance sudden violence and emotional upheaval.

Applying Yūgen to Design

As the boundless expression of implicit beauty, Yūgen takes a human-centric attitude in design. Paying far greater attention to emotional interactions, Japanese designers yearn to provoke behavioral patterns across enhanced spaces and improved experiences, both physical and digital.

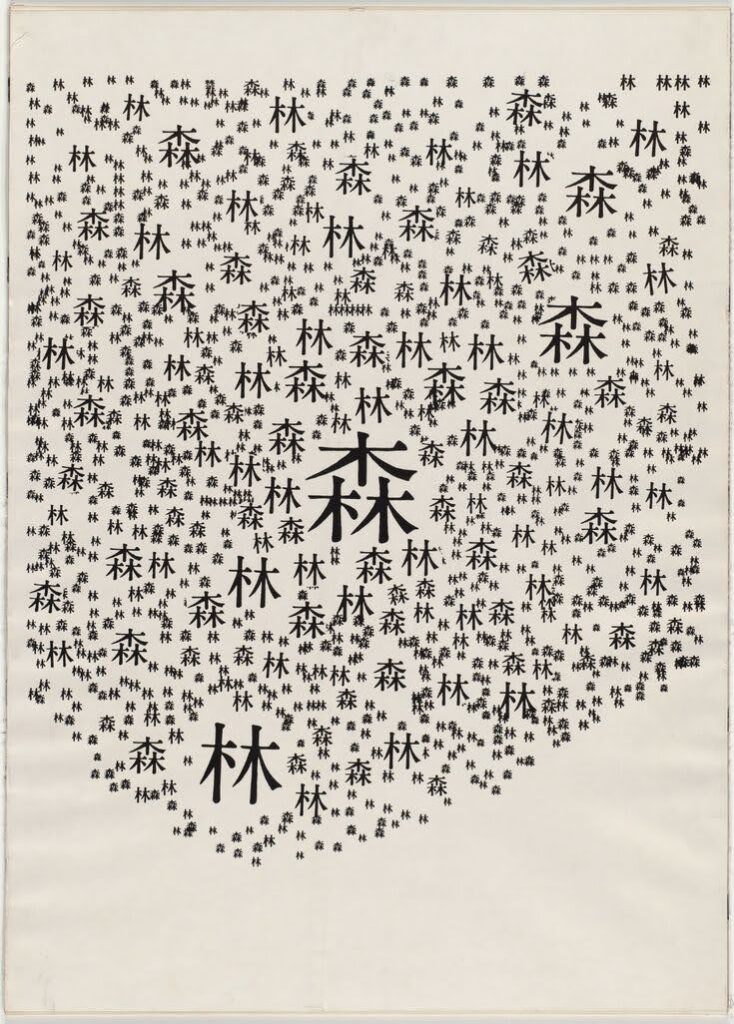

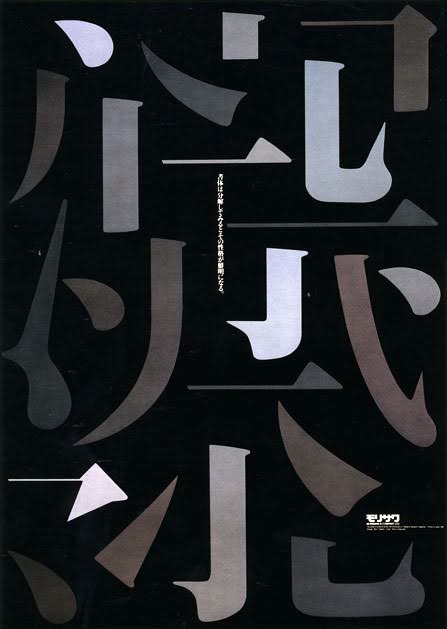

Ryuichi Yamashiro’s 1954 typographic poster for the Forest Protection Movement, titled Forest, uses the kanji alphabet in elegant rhythmic repetition to promote tree planting and condemn deforestation. The white space along the edge of the print moves towards the forest in threat.

In marketing, Yūgen inspires mystery, prompting consumers to explore a brand’s narrative several steps further.

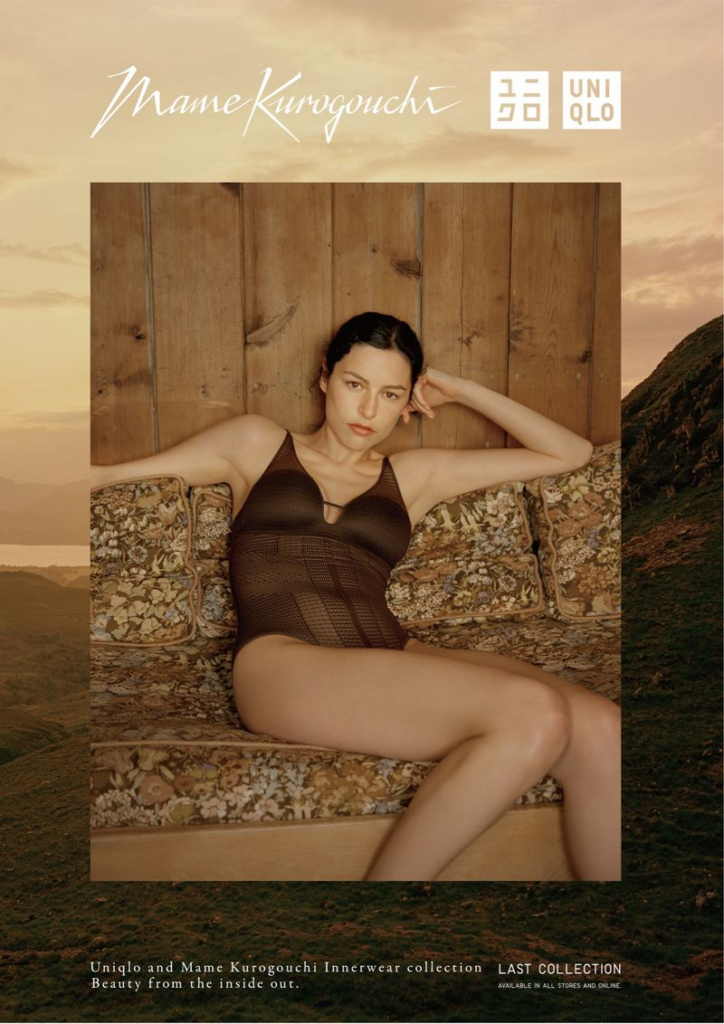

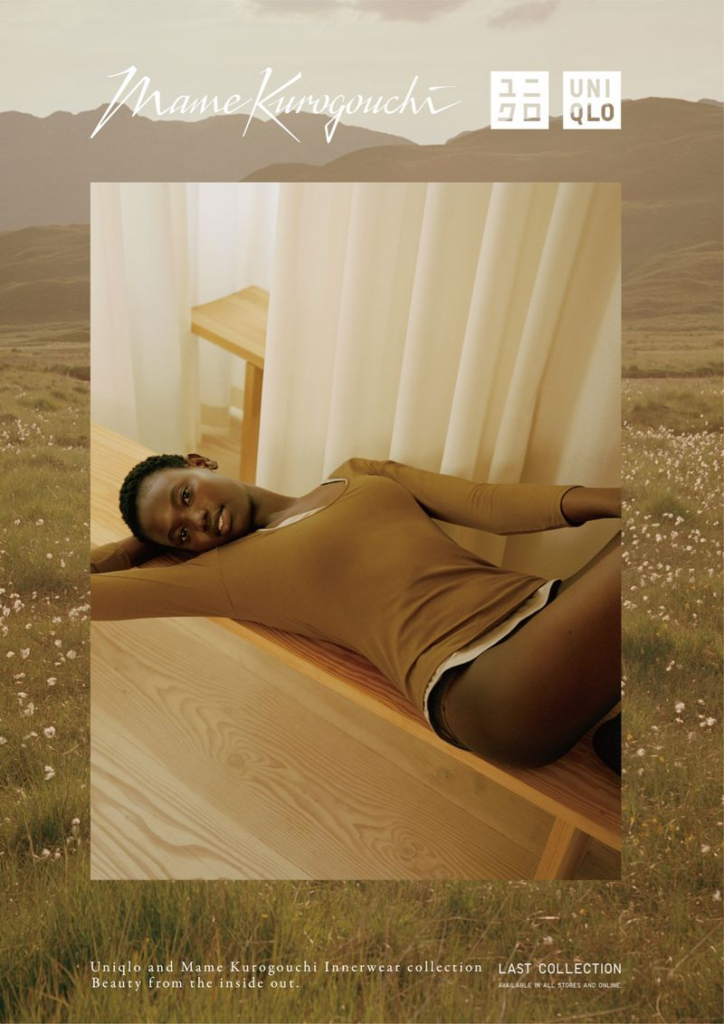

While the concept remains an elusive and obscure topic in the West, UNIQLO x Mame Kurogouchi’s FW23 campaign commands a sense of confidence and comfort with soothing backdrops, color gradients, and nature emphasizing the pleasant feeling when clothes and skin come in contact.

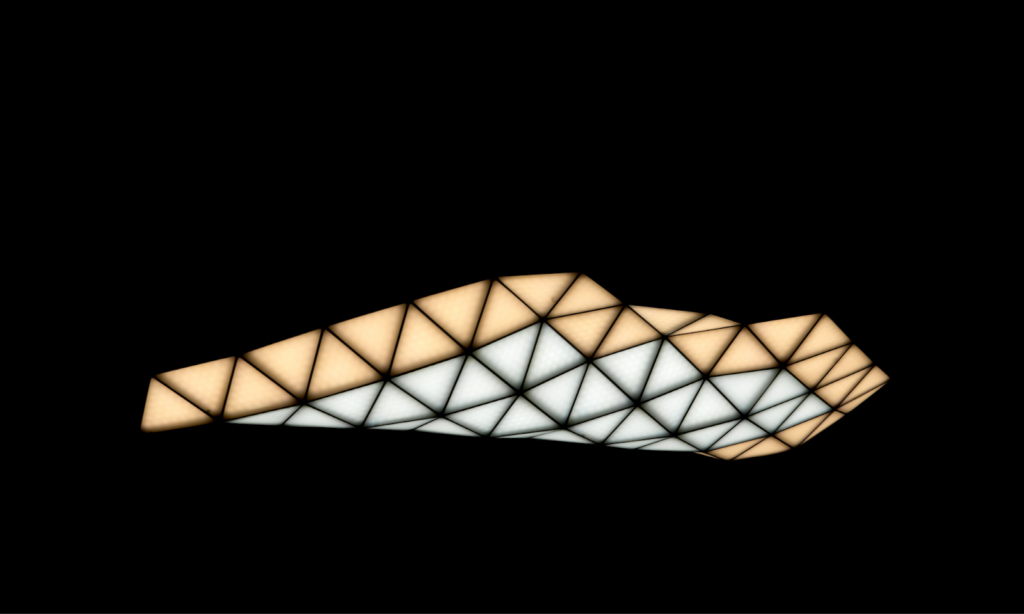

One way designers can provoke a sense of mystery from a human-centric lens is by intentionally keeping areas or parts in the dark, applying different combinations of brightness and shadow. Tokio’s TRI LIGHT exhibits the sculptural force of nature’s infinite expansion with its fully-configurable triangle design.

The fixture has the ability to illuminate a space and add an ethereal element to a room in infinite custom and unique sizes.

Yūgen’s art of suggestion demands clear designs alluding to beauty in subtle and suggestive elements.

2. Kanso (簡素): The art of clutter-free simplicity

Kanso is the ancient Japanese aesthetic belief that seeks inner peace through simplicity and minimalism.

Aligning perfectly with modern minimalist tendencies of Japanese architecture and interior design, Kanso is one of the seven pillars of Wabi-Sabi—or the acceptance of transience and imperfection.

Kanso speaks of the elimination of clutter, excluding anything that is not essential in favor of the understated elegance of quiet strength.

Under this aesthetic, simplifying leads to a fundamental appreciation for the meaning of life, not about having less, but about making room for more: more time, more peace, and more freedom.

Japanese Minimalism

The main idea behind Kanso is that the ease of empty spaces leads to a greater attention to the essence of whatever is being highlighted in turn. At the heart of this concept lies the art of minimalism.

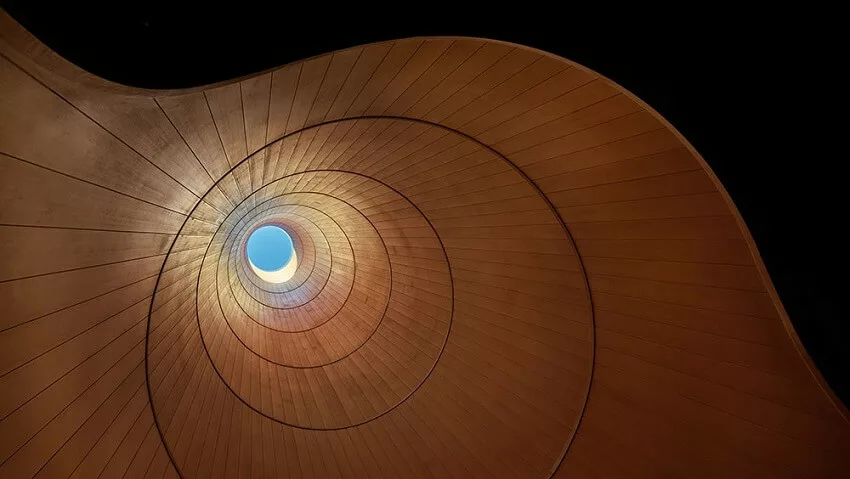

Japanese minimalism was born from the country’s Zen Buddhist tradition and its “less is more” principle. Regarded as being more intuitive, asymmetric, warm and fluid, its aesthetics are characteristically clean.

Led by simplicity and functionality, an emphasis on elegance and refinement (Miyabi, 雅), and the elimination of unnecessary elements, the use of emptiness, negative or white space (Ma, 間) is widely regarded to highlight a feeling of comfort and rationality in the viewer.

Nature also plays a key role, from the use of organic textures, patterns and materials, to its use of neutral colors, light, and seamless fusion with the outside world.

Ikko Tanaka

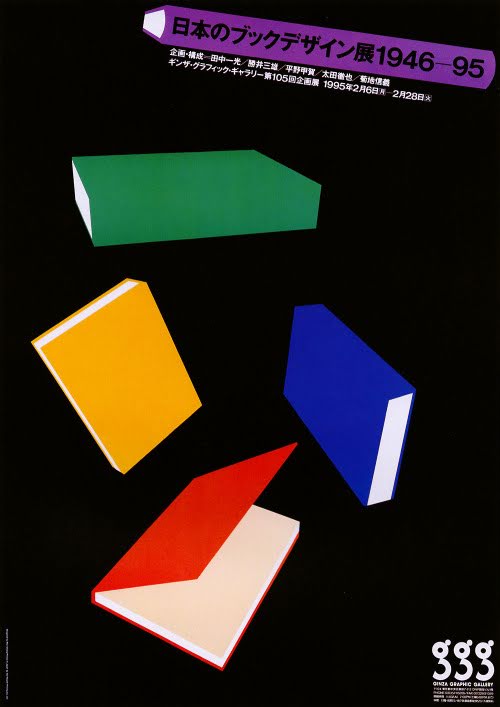

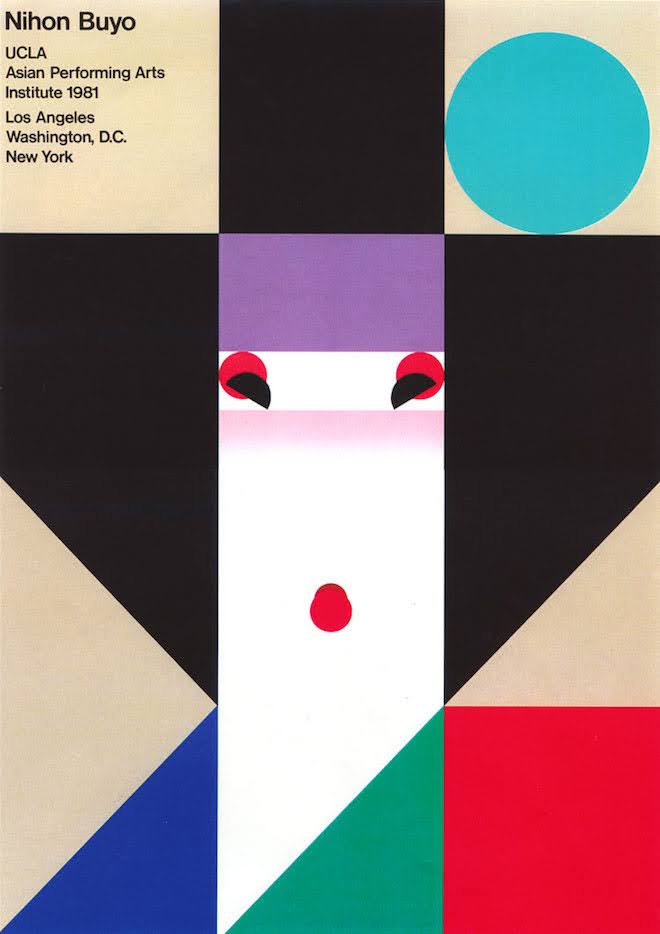

Ikko Tanaka is one of the giants of Japanese graphic design in the second half of the twentieth century. His designs are characterized by a harmonious blend of traditional Japanese aesthetics and modern graphic techniques, resulting in visually striking and culturally resonant creations.

Geometric forms and a limited color palette evidence of his high regard for the Bauhaus. Tanaka’s playful approach is seen in his iconic Nihon Buyo poster, created for a traditional Japanese dance performance at the Asian Performing Arts Institute of UCLA in Los Angeles.

The poster’s grid foundation illustrates a simplified geisha in limited colors and shapes successfully capturing the traditional characteristics of her look.

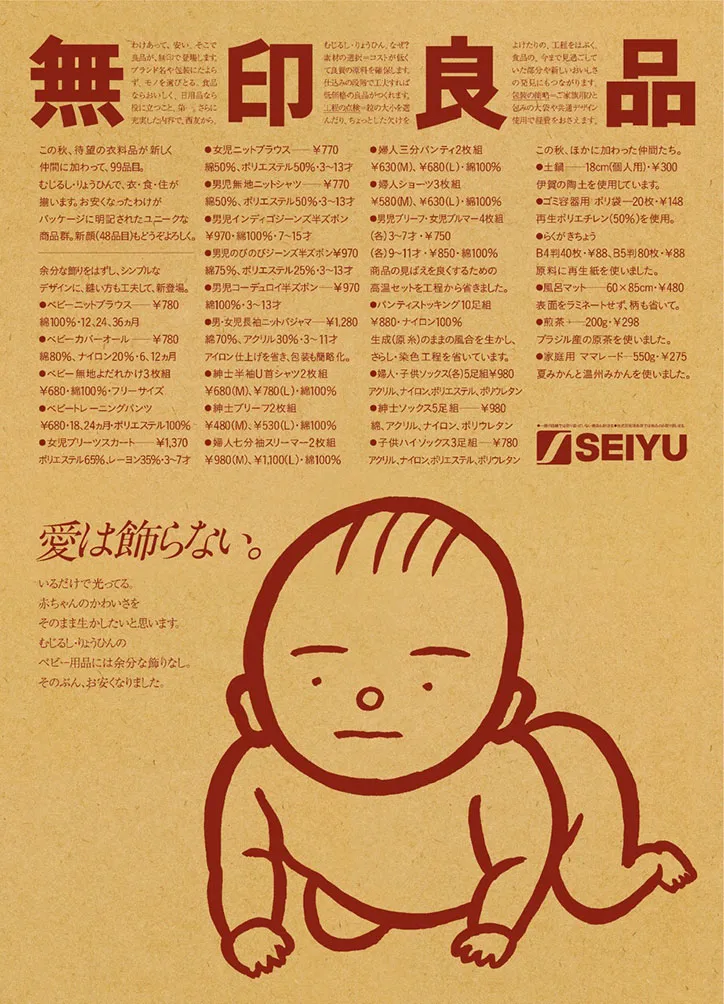

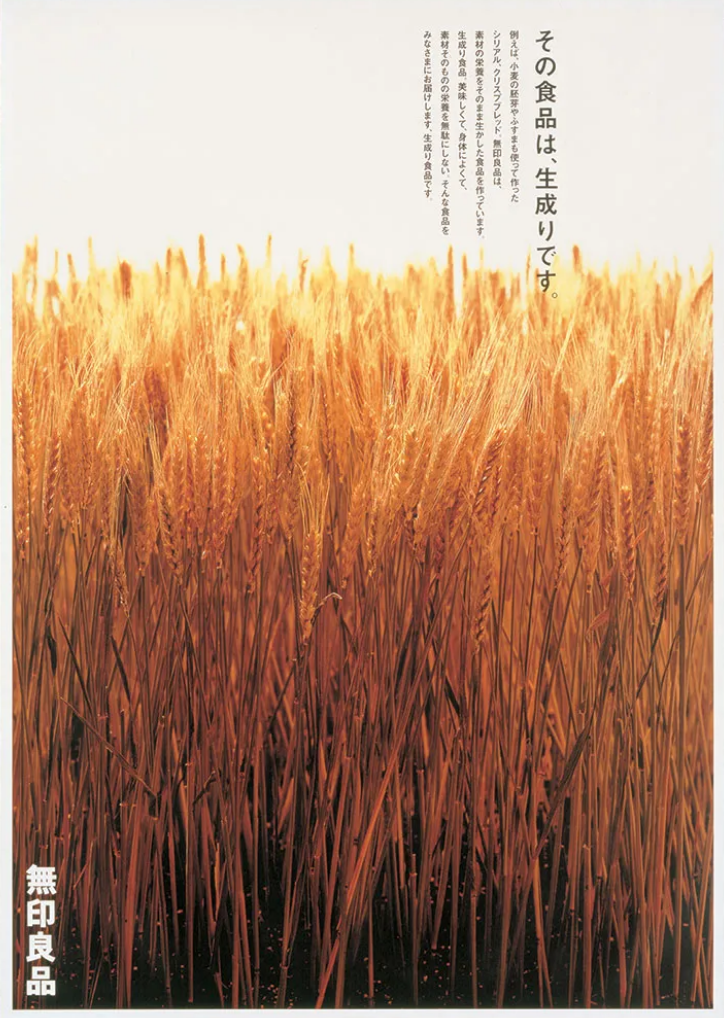

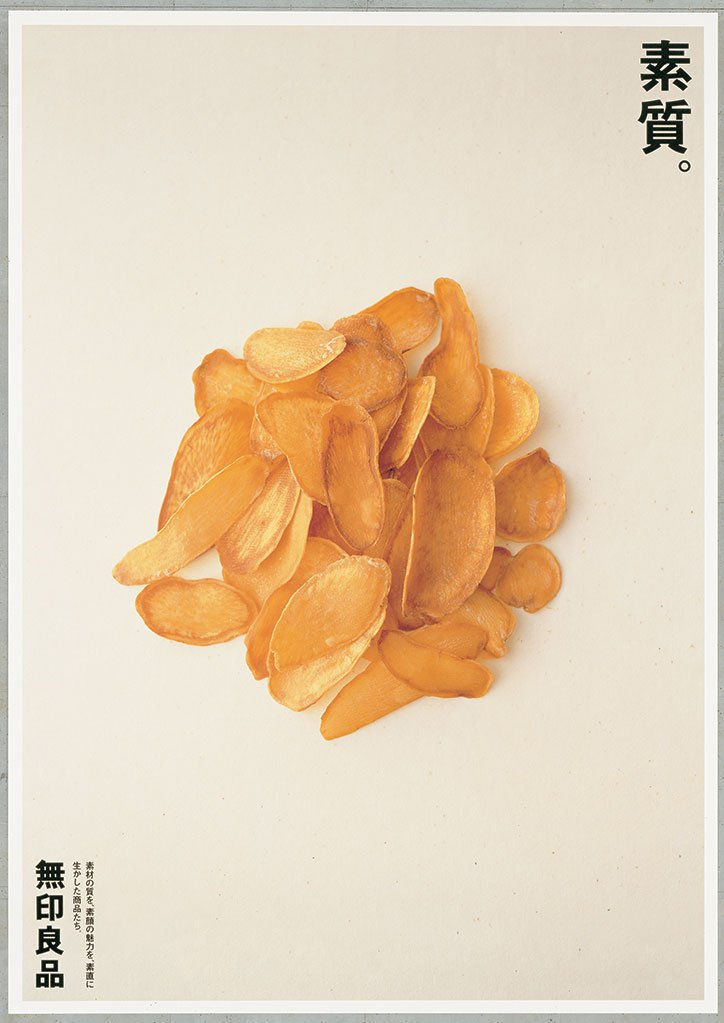

For MUJI, the global Japanese retail company, Tanaka illustrates the power of simplicity.

His serene and minimalistic approach shaped the brand’s design policy and visual direction, which are still present to this day: limited text, neutral backdrops, single subjects, simplified forms and clean aesthetics all emphasize MUJI’s unwavering commitment to material quality in its purest form.

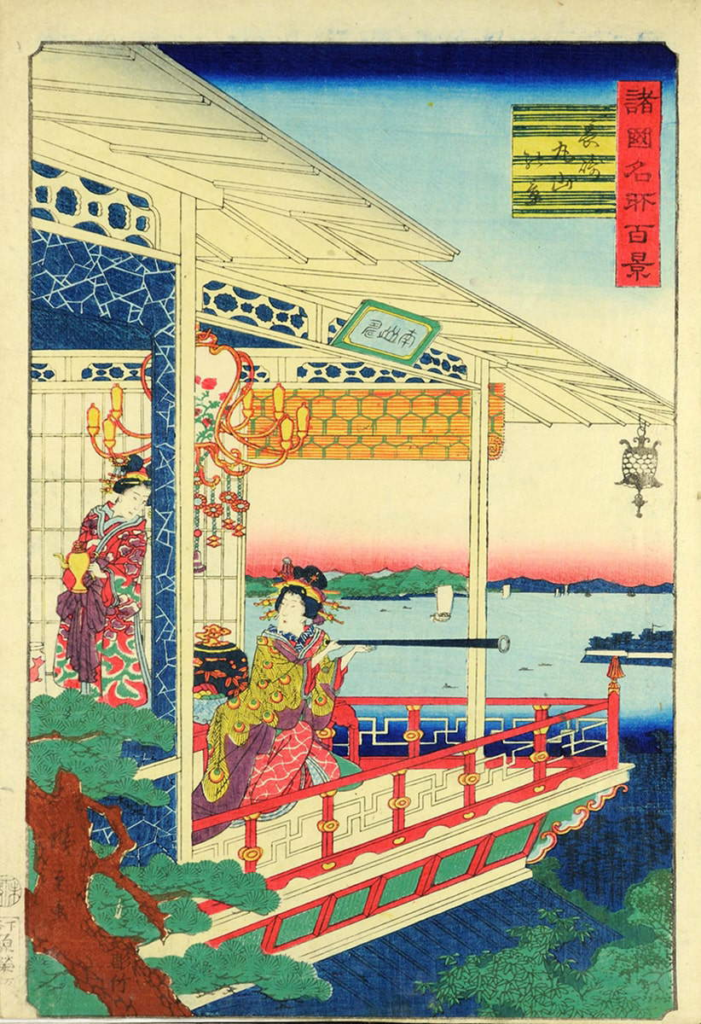

Ukiyo-e

The idea of working with fewer elements echoes the deep-rooted feeling of Kanso, and the art of Ukiyo-e shaped both Japanese and Western design we see today.

Ukiyo-e woodblock prints depict scenes of daily life, landscapes, Geisha ‘beauties’ and Kabuki actors, heroic and folk tales, and erotica. Its aesthetic gives value to simplicity, relying on flat spaces, solid bold colors and arabesques on a single plane of depth to evoke a poetic representation of reality.

During the Edo period (1603-1868), Ukiyo-e were considered forms of mass entertainment, serving like present-day fashion magazines highlighting the latest styles, from Kimonos to vibrant fans.

Ukiyo-e exerted a significant influence on Western art, too. First exhibited at the World Exposition held in Paris, France, in 1867, ukiyo-e brought a major Japanese traditional art movement to Europe in the late 19th century known as Japonisme, attracting the attention of the Impressionists in their early years, and captivating renowned figures such as Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh, and Edgar Degas.

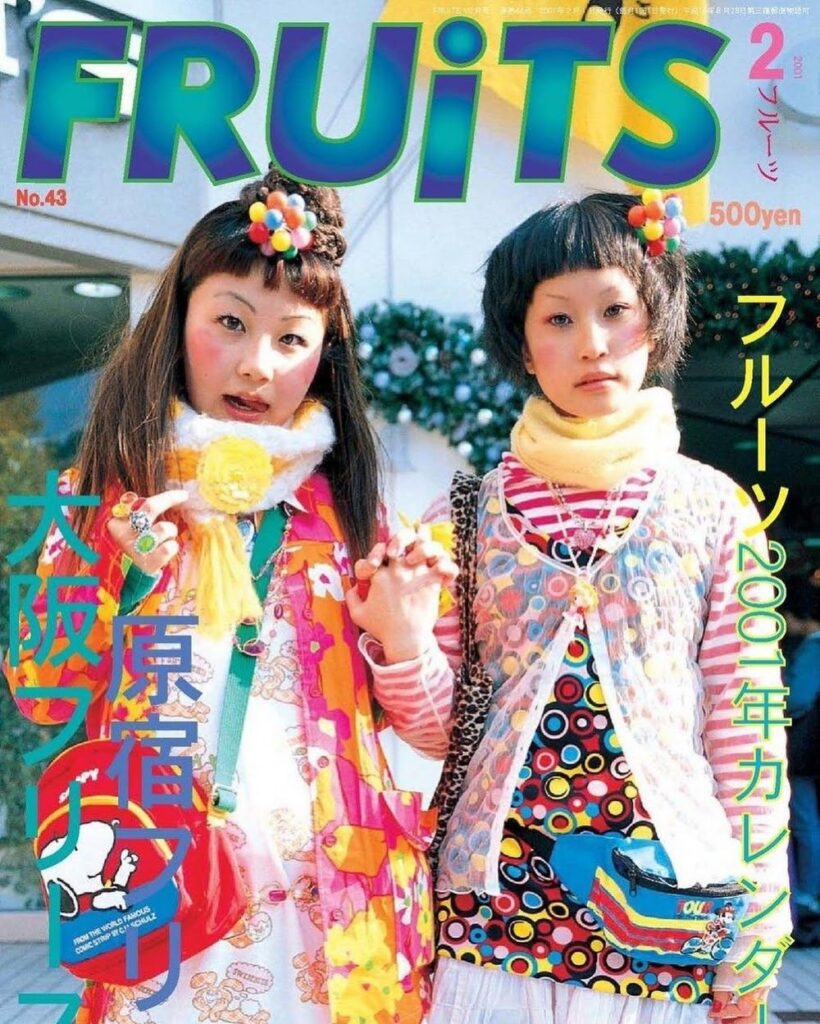

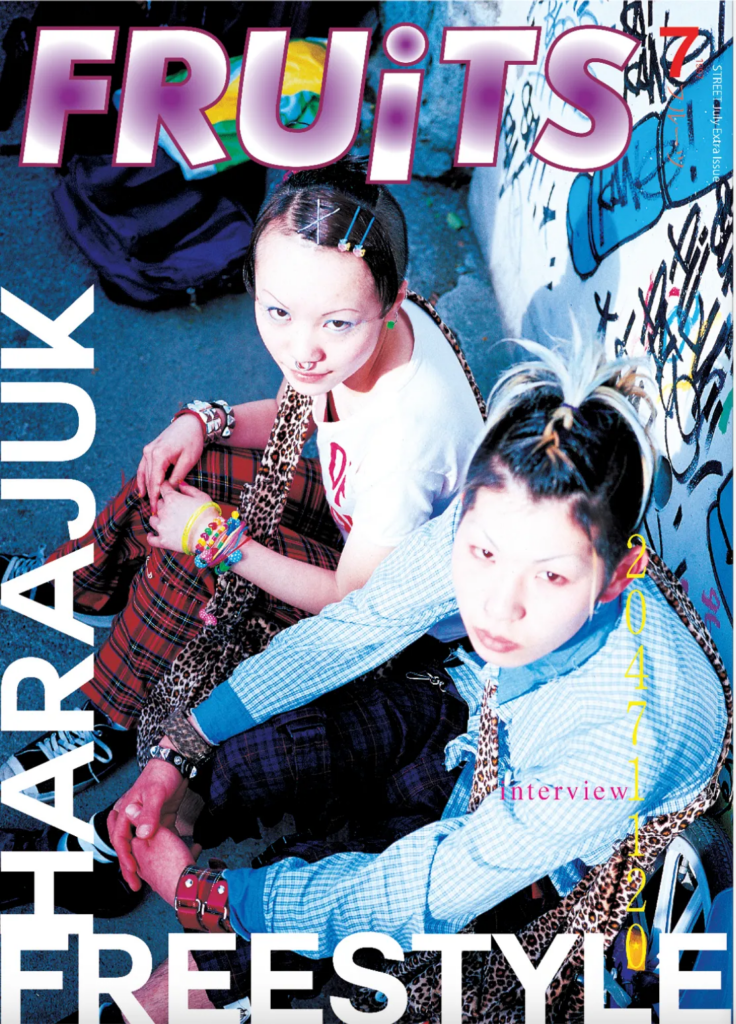

FRUiTS

Long after ukiyo-e showcased the most radical fashion and fabrics of the time, and long before street style photographers captured the most unique outfits of our present, there was FRUiTS—the monthly street fashion magazine published from 1997 until 2017 and founded by Japanese photographer, Shoichi Aoki.

Credited with popularizing street snaps, FRUiTS chronicled the style of the different groups of young people that often hung out in the Harajuku neighborhood of Tokyo. The publication featured a simple layout, with the bulk of the magazine made up of single full-page photographs accompanied by a brief profile of the photographed person.

The magazine primarily focused on individual styles found outside the fashion-industry mainstream, as well as subcultures specific to Japan, such as lolita and ganguro, and local interpretations of larger subcultures like punk and goth who would not only sport popular brands like DC Shoes, Comme des Garçons, Vivienne Westwood, and Hysteric Glamour, but also DIY pieces, like tie-dye and crocheted items, and traditional Japanese clothing, like kimonos and geta (wooden footwear).

FRUiTS helped lead global interest in Japanese fashion as some of its photographs became first popular in the fashion community, then synonymous with Japanese fashion in the West. Today, and over 25 years later, its first issue is available in English as an ePub with the goal to bring back the whole catalog of 233 issues into circulation in English and introduce new generations to its universe.

Applying Kanso to Design

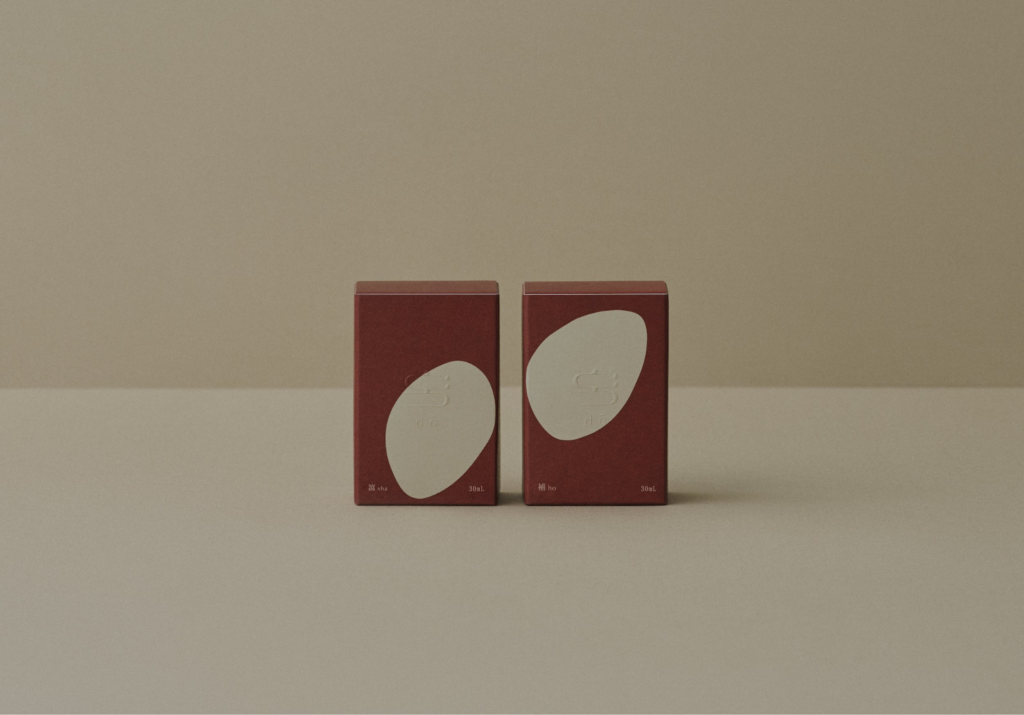

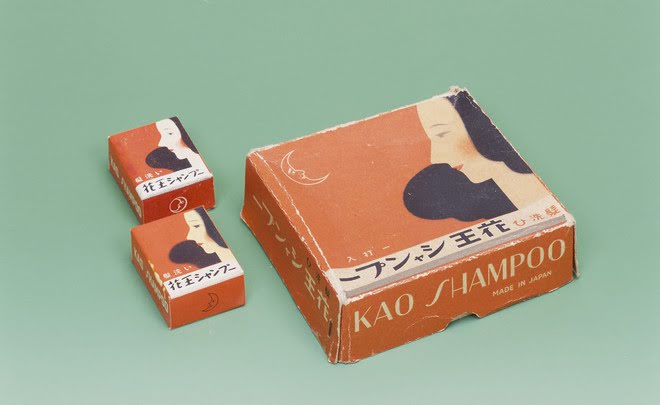

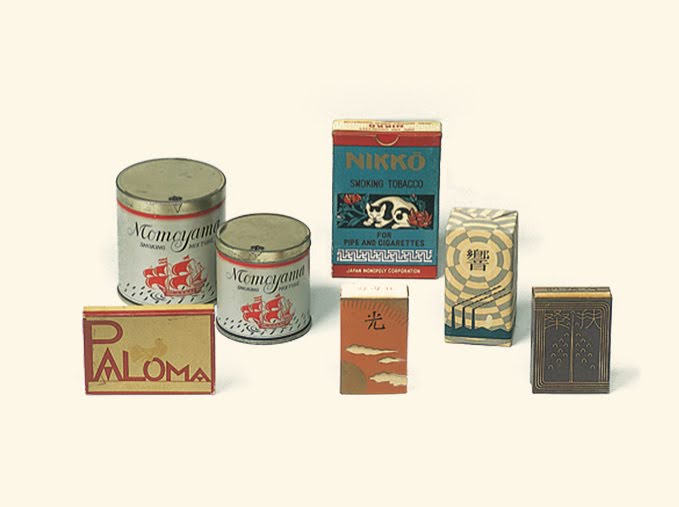

Characterized by its simplicity and liberal use of empty space, Kanso has been embraced globally by way of Japanese minimalism, influencing design trends across disciplines such as technology, fashion, and product packaging, as well as architecture, interior and graphic design.

Japanese beauty, or J-Beauty products are certainly not a new phenomenon, but there’s no denying that the simple and minimalistic aesthetics that characterize its packaging continues to allure. Clutter-free designs make it easy for users to engage with brands.

underline graphic.inc’s packaging for LORETTA AIMER showcase the diversity of individual personalities that the haircare brand caters to in designs that blend seamlessly with their living spaces. While little lightning’s use of kanji plays a significant role in dō’s signature nature-inspired nail products visualized with asymmetrical, organic shapes.

In UI design for digital products, white space leads a user-friendly approach as it helps to bring attention to the most essential content and empowering visitors to navigate web pages or screens easily. Tokyo-based creative digital production team, Garden Eight, combines a characteristic elegant style with a sensible application of animations and effects.

In fashion, Issey Miyake’s quiet but powerful minimalist designs composed of molded and pleated clothing explores the space around the wearer as well as within the pieces, escaping gender stereotypes combining Eastern and Western elements. His collections featured a limited color palette and sophisticated, simple cuts.

Miyake’s approach to business and fashion, as well as technology and sustainability, make him one of the most innovative and important figures in the industry.

3. Datsuzoku (脱俗): Breaking free from daily routine

Datsuzoku is the aesthetic that challenges our creativity away from convention.

A fundamental concept of Japanese culture and way of life, Datsuzoku encourages us to engage in different experiences instead of what is expected from us. It enables us to break from the ordinary with newfound approaches in order to achieve the unusual.

Datsuzoku delves into the myriad of possibilities that come from breaking patterns and favors the exciting uncertainty that makes the unknown so appealing. The belief behind this concept is that freedom from habit results in spontaneous streams of creativity.

As one of Wabi-Sabi’s seven Japanese aesthetic principles, Datsuzoku encourages individuality outside the confines of society’s expectations and traditional norms leading to new ideas and perspectives, and a more authentic, meaningful and fulfilling life.

Japanese Modernism

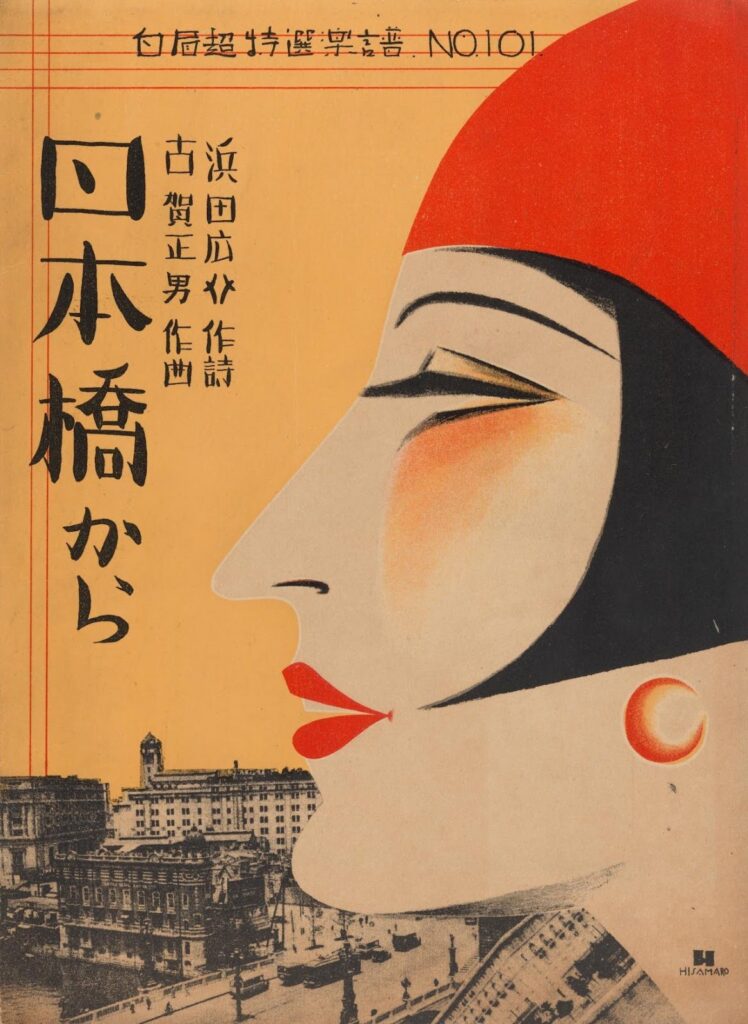

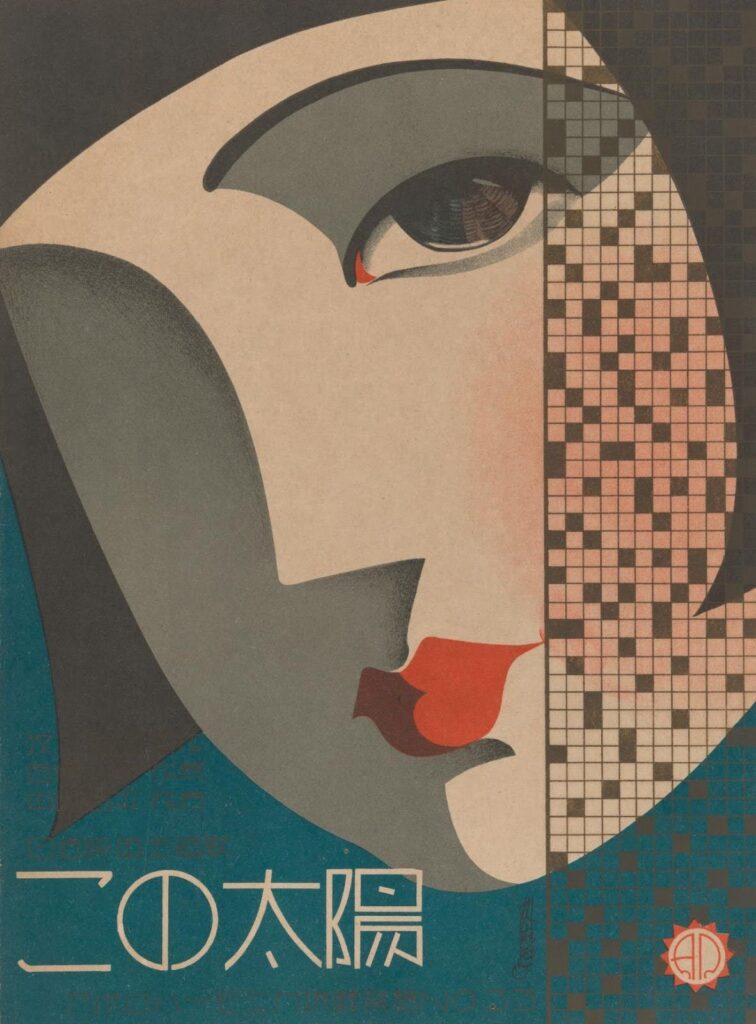

The cultural exchange between the East and the West from the early 1920s until the late 1930s laid the foundation for Japanese Modernism, the creation of Asian Art Deco and the surge of Avant Garde. Such fusion of Japanese and Western artistic elements manifested in different formats with a strong emphasis on lines, curves, irregular shapes and uncomplicated decorative elements.

Japan’s lively consumer culture felt the influence of new technologies from abroad, attracting a new generation of urban pleasure seekers and consumers, known as moga and mobo (modern girls and modern boys) into the glamorous cities. Capturing the spirit of a rapidly evolving country and its exuberant youth were fashion, decorative arts, popular culture and design.

Traditional woodblock printing techniques combined with mechanized color printing demonstrated the evolution of Japan’s aesthetic vision, attracting graphic designers, illustrators and photographers to leading avant-garde visual aesthetics and predominant social trends from Europe at the time—Fauvism, Cubism, Suprematism and Futurism—resulting in a new and playful East–West hybridity.

As such, Japan’s bond with Scandinavia should come at no surprise, thanks to Japanese interiors being transferred into the design of European houses and inspiring a whole wave of designers. It was also then that the Japanese concept of “everyday art” or Yo-no-bi first entered the mainstream.

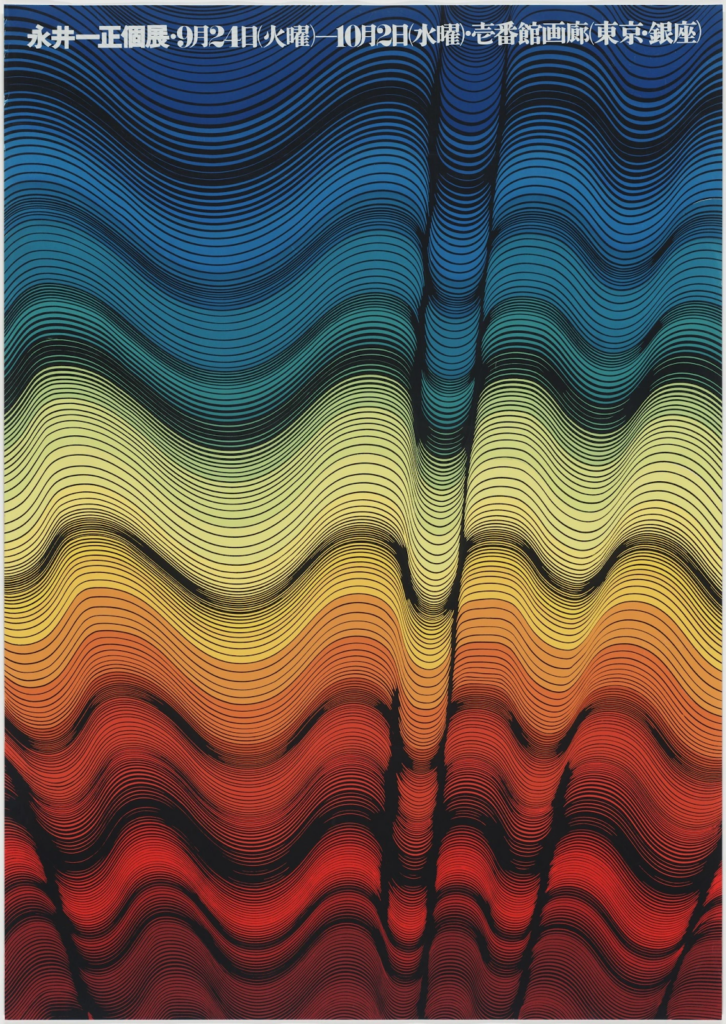

Yusaku Kamekura

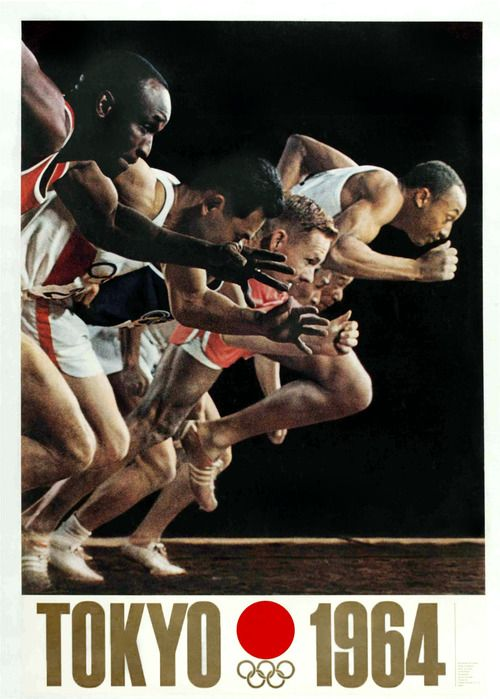

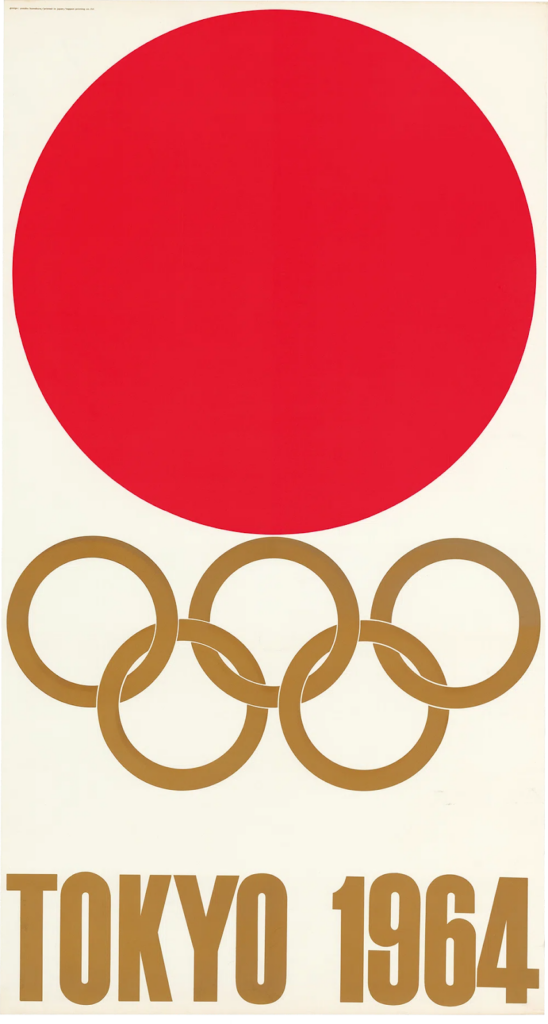

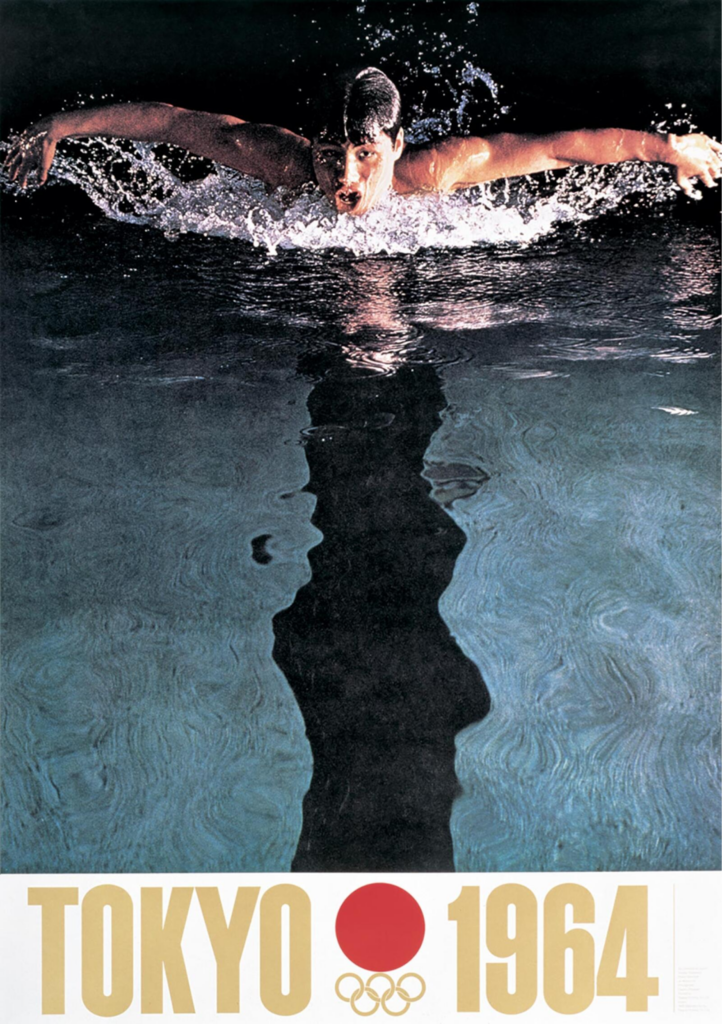

Regarded as the father of Japanese graphic design, Yusaku Kamekura was paramount in cementing Japan’s post-war identity. His vision championed abstract geometric forms accented with bold and solid color palettes, carrying on Japan’s traditional expression and iconography in posters, corporate symbols, trademarks, and book covers.

First presented to the world in 1961, Kamekura’s iconic ‘Tokyo 1964’ logo for the Tokyo 1964 Summer Olympics effortlessly combined Japanese iconography with modernist aesthetics, while the event’s pictogram designs by Katsumi Masaru and Yoshiro Yamashita brought down language barriers leaving a lasting influence on the standard visual identity of major international sporting tournaments from then on.

Influenced by the Bauhaus, Kamekura’s mark designs represent his bold elimination of waste, combining simplification derived from Japanese traditional family crests, Western mechanics and a sharp modern sense of composition.

Kamekura was also pivotal in establishing the Japan Advertising Arts Club (1951), the Japan Graphic Designers Association (1978) and the Nippon Design Centre in 1959.

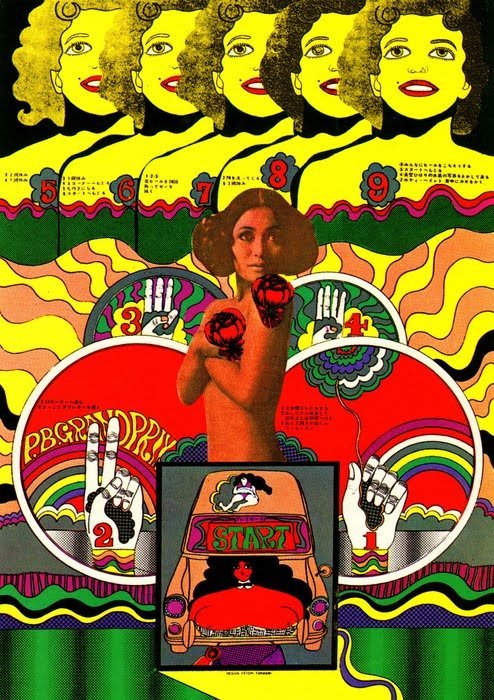

Japanese Avant Garde

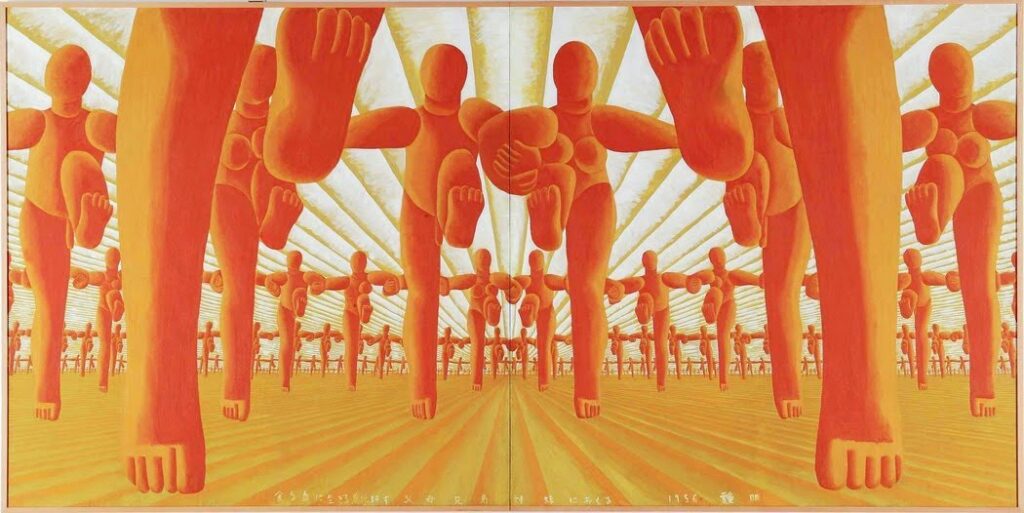

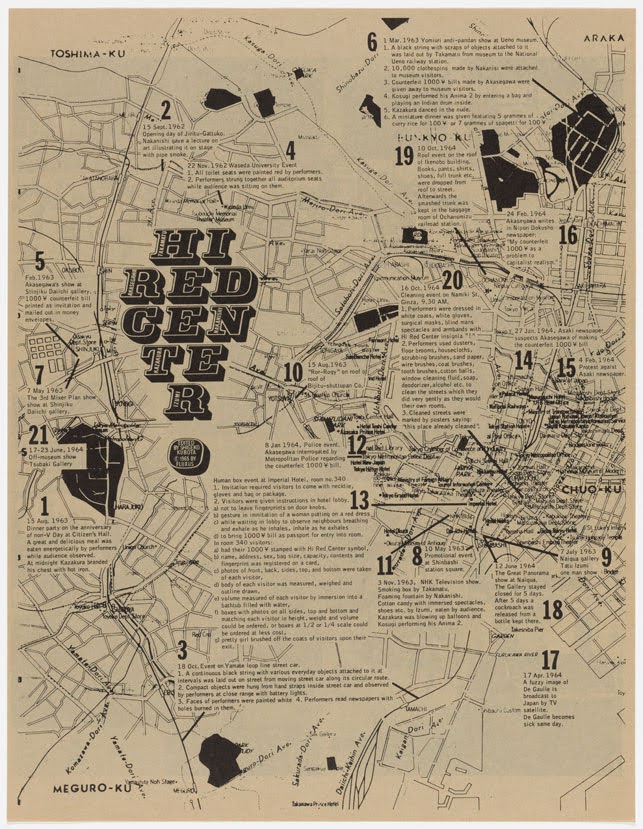

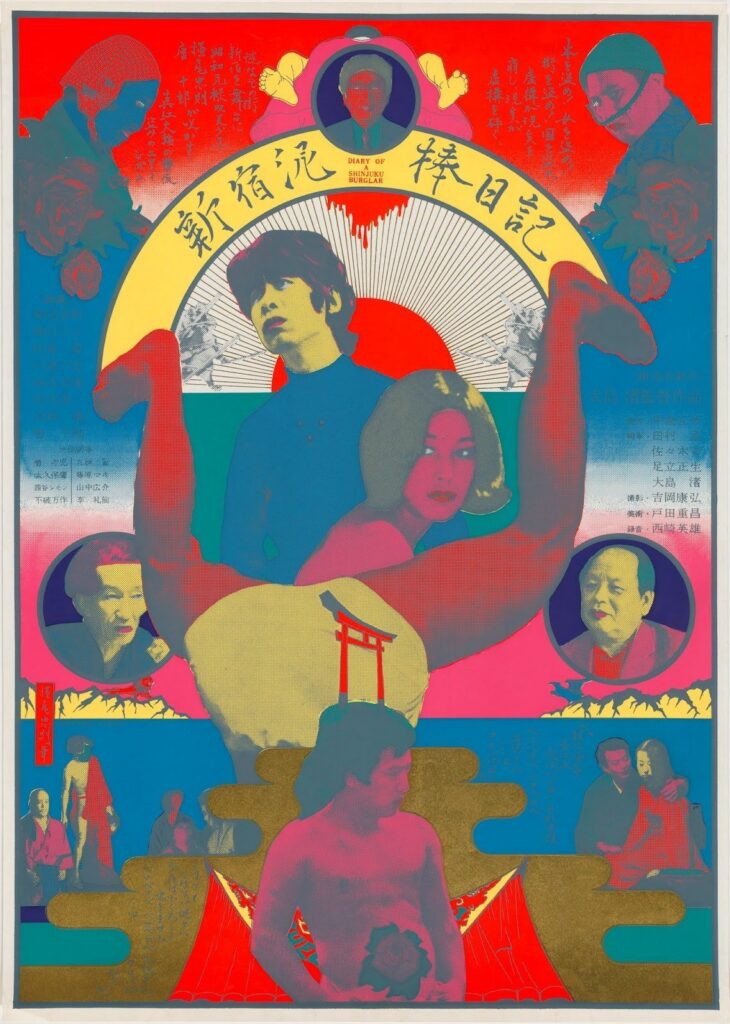

An extraordinary concentration of creatives changed Japan from a war-torn nation to the international center for arts, culture, and commerce between the mid-1950s and 1970s.

Japan’s post-World War II era championed the spirit of Datsuzoku through boundary-pushing innovation, individuality, and experimentation, laying the foundations for Japanese Avant-garde.

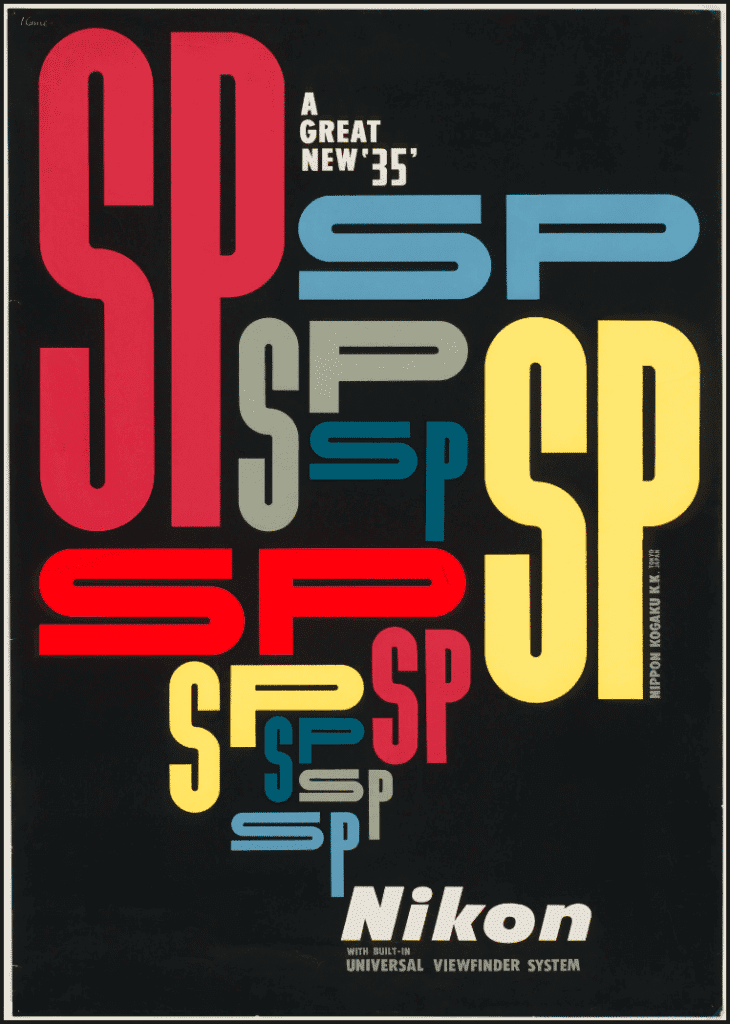

Pioneered by a rapidly growing modern metropolis and Western influences, Japanese Avant-garde is defined by its embrace of pop culture and its fusion with traditional styles and symbols.

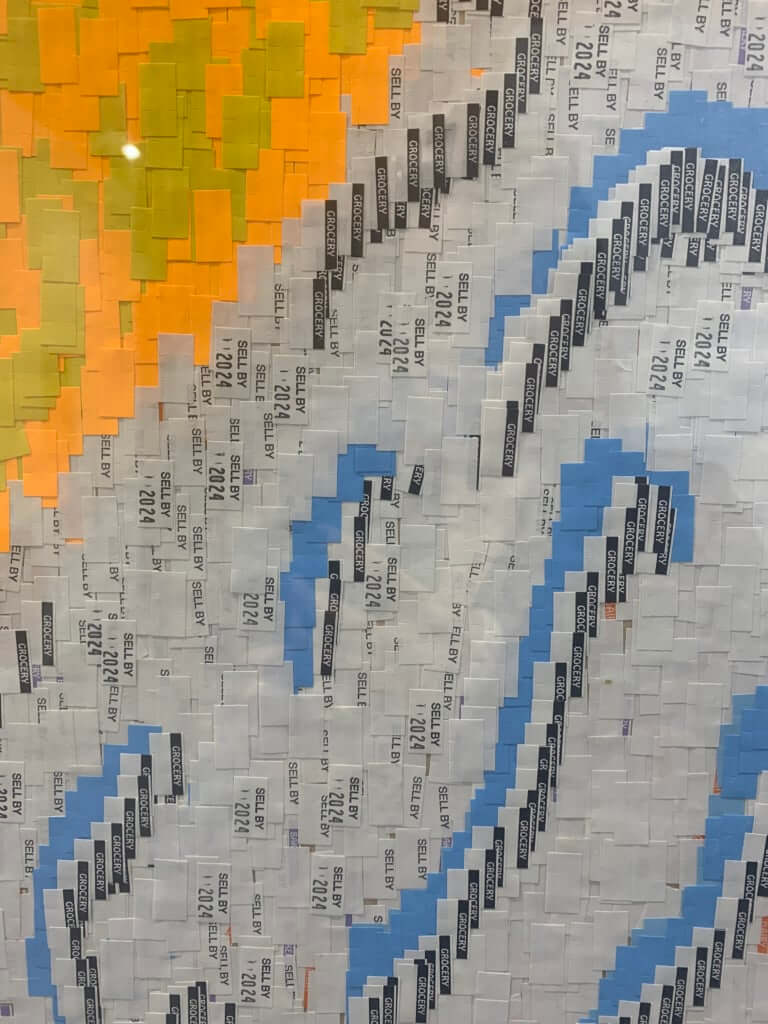

Large-scale multimedia, performance art, fragmentation, obsessive repetition, bold “super-flat” compositions, “anti-art,” experimental art, asymmetry, and deconstruction embody its unique aesthetic.

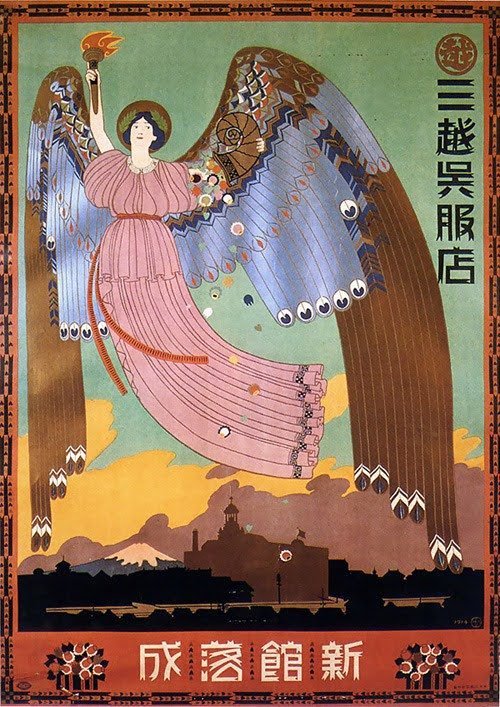

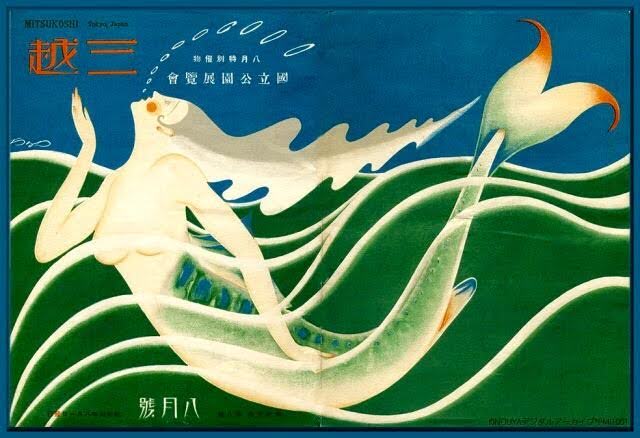

Hisui Sugiura

From adverts to branding, it’s common to see unconventional materials, clashing colors, boldness and abstract concepts in Japanese design. This can be attributed to Hisui Sugiura, one of Japan’s most gifted graphic designers.

Heavily influenced by Art Nouveau and Art Deco, Sugiura is best remembered as the artistic brain behind Mitsukoshi Department Store, largely responsible for signboards, posters, and covers for PR publications. His posters incorporated modern art trends and artistic ideas of the time capturing the energy of ‘The New Woman,’ or atarashii onna—the first generation of the newly socially liberated woman of modern Japan.

His interest in Europe’s art nouveau movement led him to form the artist collective known as Shichinin-sha, aka the Group of Seven, which led the early stages of Japanese commercial design.

Simple, flat, and stylized forms, clear coloring, and playful typography are evident in his poster work.

Applying Datsuzoku to Design

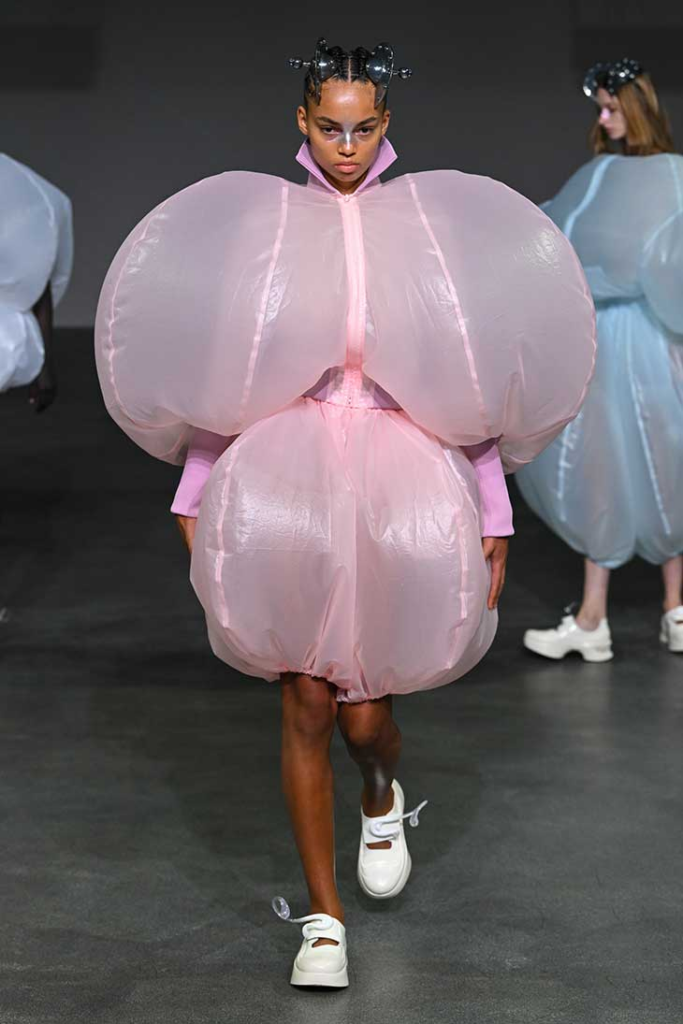

It’s hard to ignore the influential parallels between Japanese modernism, minimalism and avant-garde in global design. Fashion trio, Yohji Yamamoto, Issey Miyake and Rei Kawakubo, have challenged long-standing notions of gender, form and function in dialogue with Japanese tradition, incorporating exaggerated volumes, deconstruction, and mindful detailing into their designs.

In the spirit of their predecessors, Junya Watanabe, Undercover’s Jun Takahashi, Kolor’s Junichi Abe and Sacai’s Chitose Abe, alongside Tomo Koizumi, Nicola Formichetti and ANREALAGE’s Kunihiko Morinaga continue Japan’s prodigious ability of avant-garde dressmaking.

Moreover, Kawakubo’s Dover Street Market ended retail as we once knew it. With locations in New York City, Tokyo, Singapore, Paris, Beijing and Los Angeles, DSM gathers top independent designers, life-size installations and architecture, leading Asia’s new wave of future-proof experiential shopping.

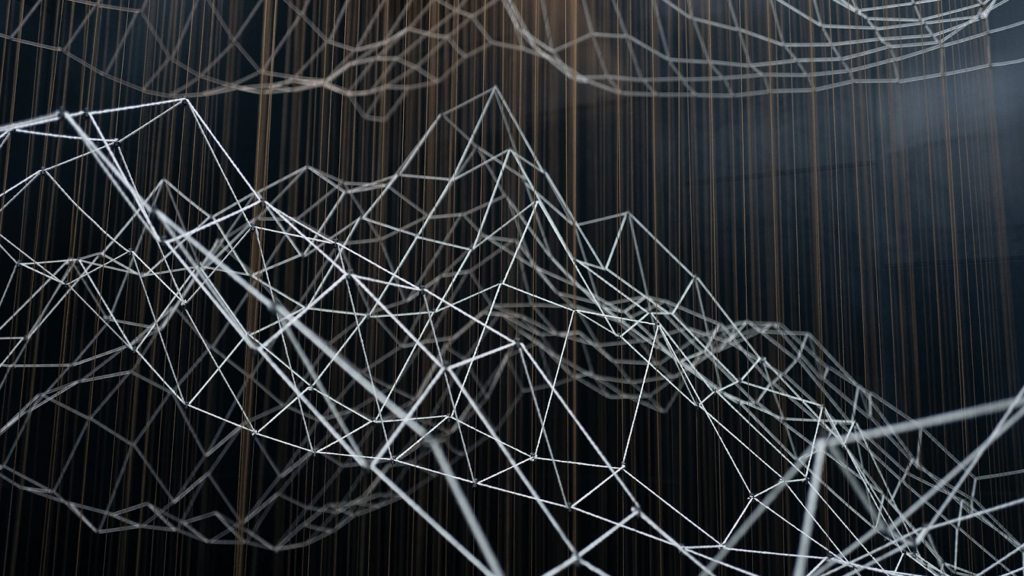

Similarly, Tokyo-based creative studio PARTY combines narrative and technology in creative installations, spatial design and interactive brand experiences.

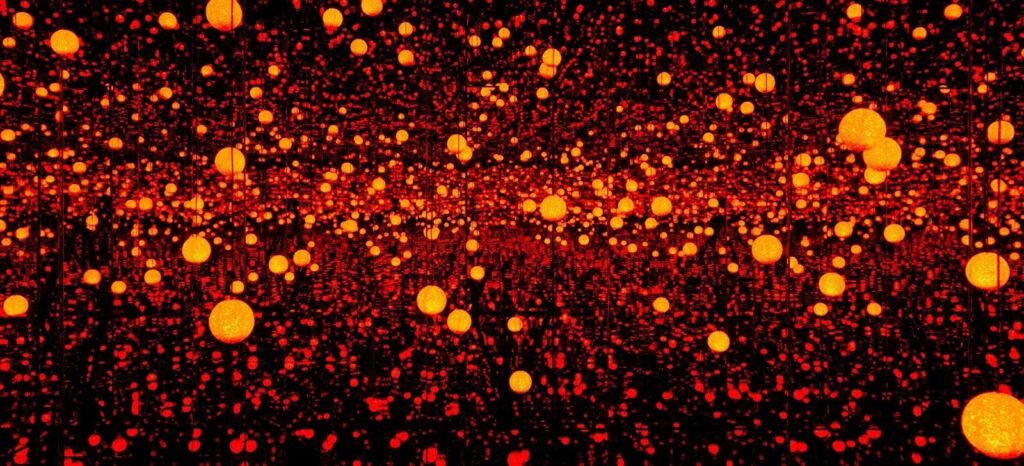

Takashi Murakami’s ‘superflat’ visual language and Yayoi Kusama’s fragmented void unlocked exonemo’s experimental installations and Whatever’s multi-media, human-focused enjoyment.

Deviating from day-to-day routine, the concept of Datsuzoku ditches predictable expectations for the element of surprise. It’s only then, when we tap into Datsuzoku, that we allow design to push boundaries, break free from monotonous formulas and pave the way for exciting creativity and new ways of thinking.