In Italy, time stretches. What was old becomes new, and what’s new takes shape in the familiarity of everyday life. Here, gestures speak louder than words do, emotions lead with intention, and beauty prevails in a layered display of restraint and radiance.

Italy carries its visual charm steeped in the romance of time, place, art, and culture. Its distinctive mark points to time-honored styles, innovation, performance, and futureproof movements that have (and continue) to impact the world of design.

Amid the algorithmic noise of omnipresent distractions, can Italian design deepen our longing for meaning, craft, cultural value, and human re-connection?

This study explores just that. We’ll dive into the hallmarks of Italian design—past, present, future—and render their lasting influence in today’s next-gen crop of graphics, product, architecture, interiors, and fashion.

An Unruly Grappling With Modernity

Spanning between the 1950s and the 1970s, the golden era of Italian design laid the foundation for its emblematic identity. The timing coincides with the country’s post-war rejuvenation period—il miracolo economico, or the Italian economic boom—and a combined focus on aesthetic appeal and artisanal know-how that excited designers over half a century ago.

Italian Graphic Design

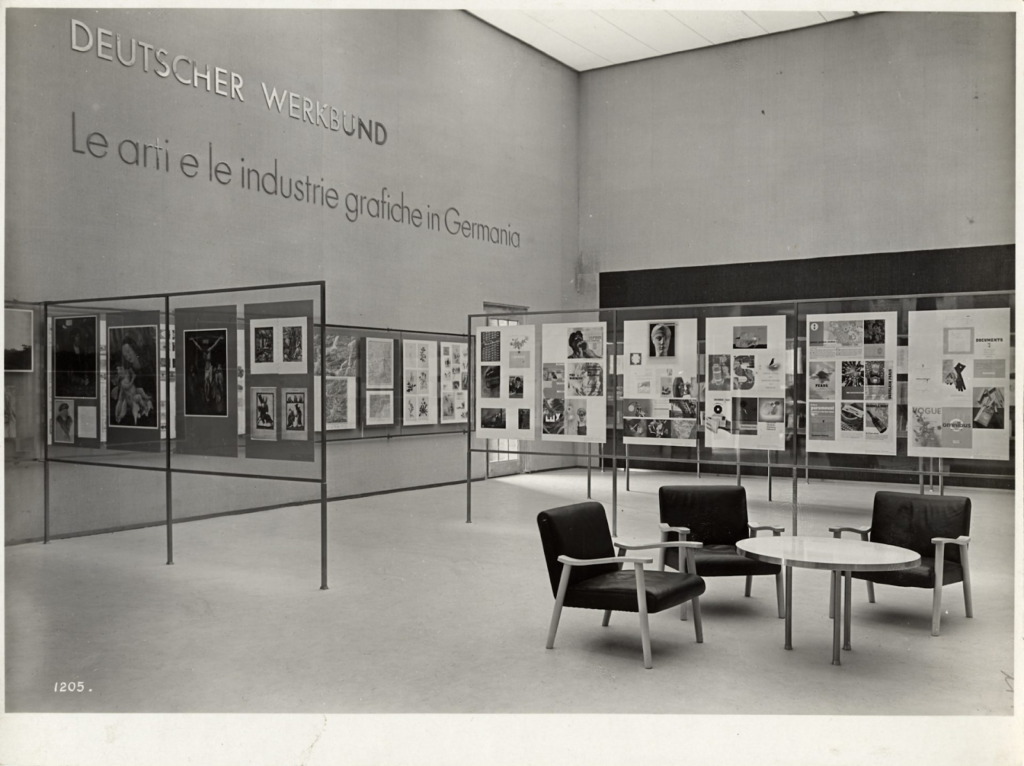

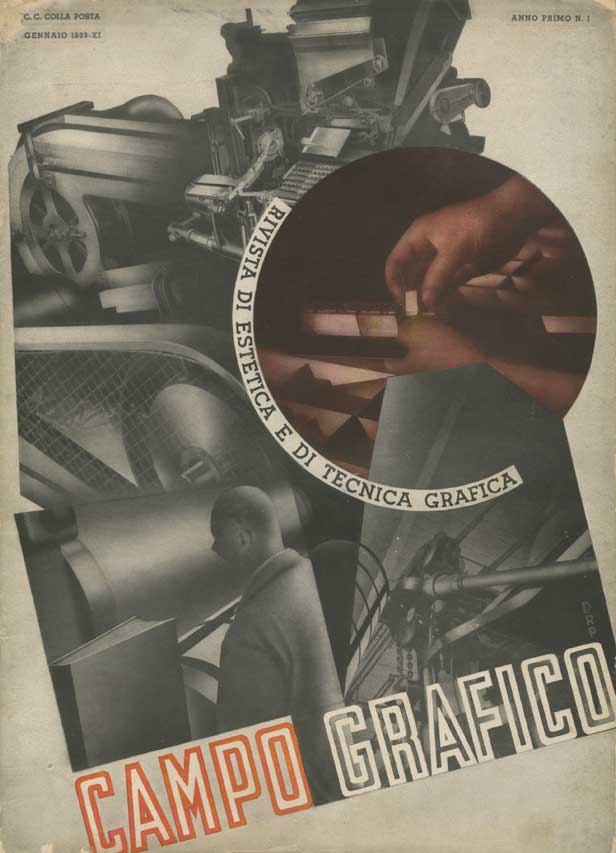

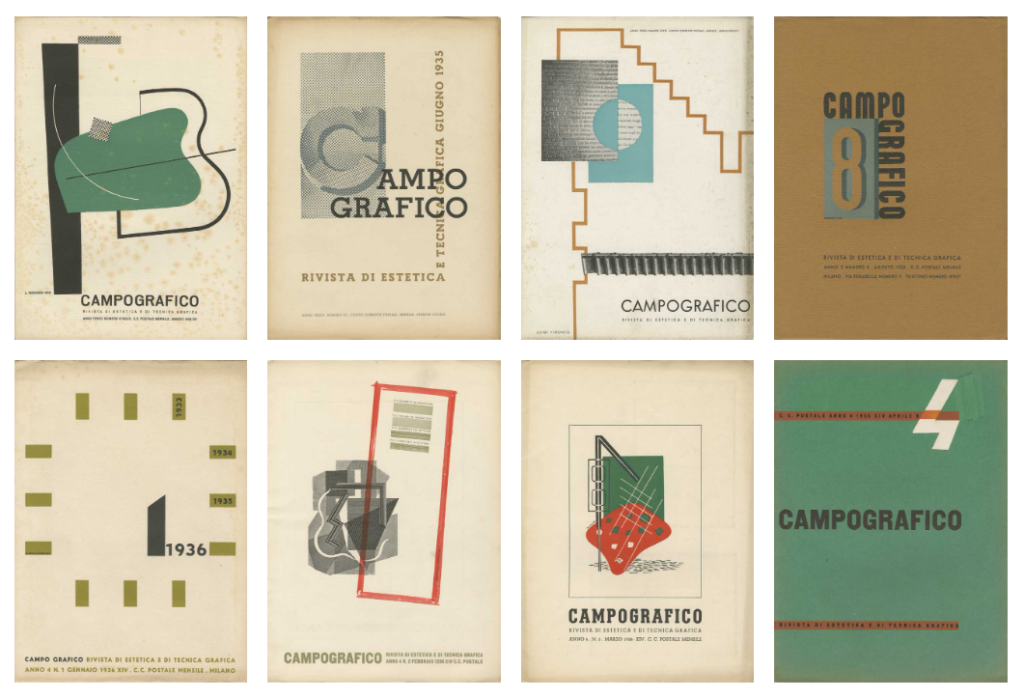

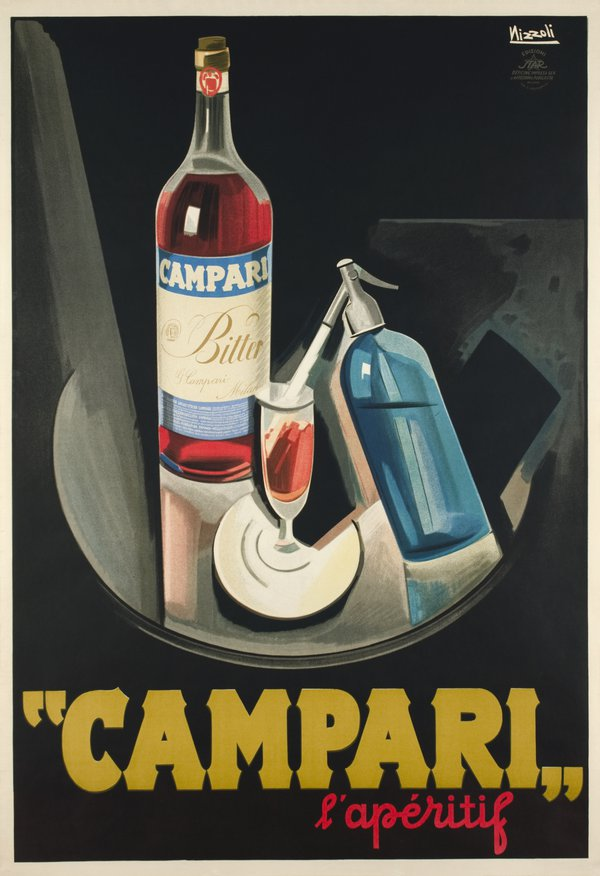

While we can trace its history back to the Renaissance, it is believed that the early-1930s marked the starting point of Italian graphic design—a discipline that pins the Milanese capital as its birthplace. Highlights from this period include the launch of Campo Grafico magazine, the founding of Studio Boggeri, the inauguration of the German Pavilion at the 5th Milan Triennale, and the arrival of Bauhaus-alum, Xanti Schawinsky.

Hindsight tells us that after World War II, the quick spread of industrialization and advanced consumer tech across Europe pushed Italy towards modernity. This shift challenged both tradition and ideology, just like the Futurist movement did in the first half of the 1900s for architecture, graphic design, and product design against the Rationalist school of thought of the fascist establishment.

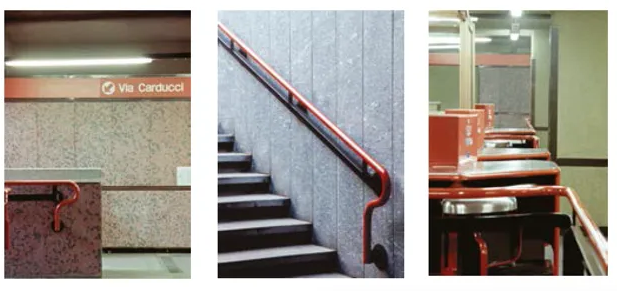

The newfound visual order that stemmed from Italy’s golden age blurred the lines between art, function, and technological innovation. Elegant corporate identities, modern advertising, branding, and other commercial uses of design soon replaced old projects for radical political groups.

Characteristics of Italian Graphics

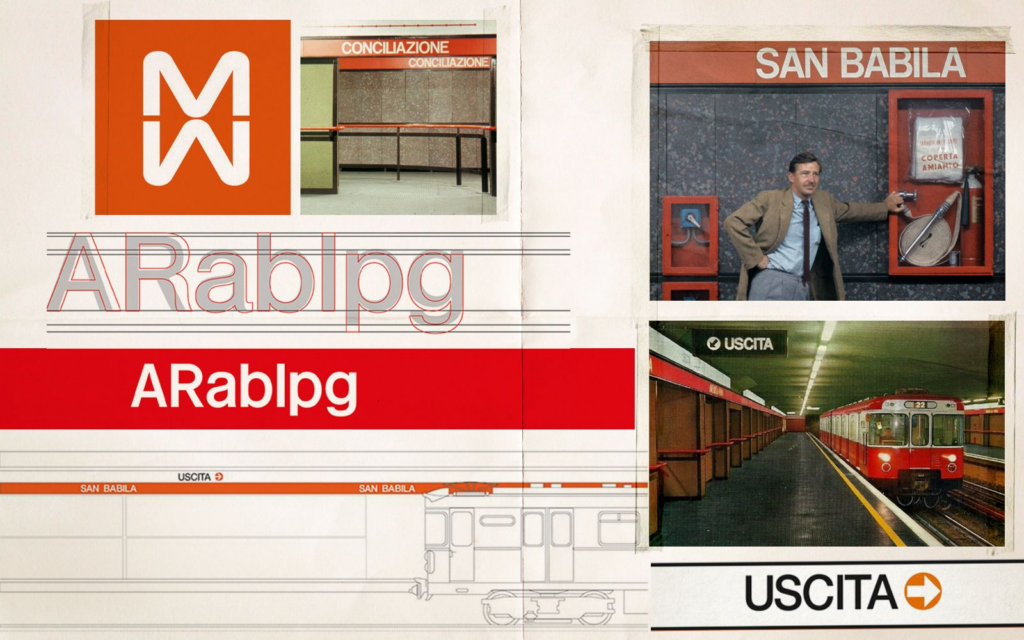

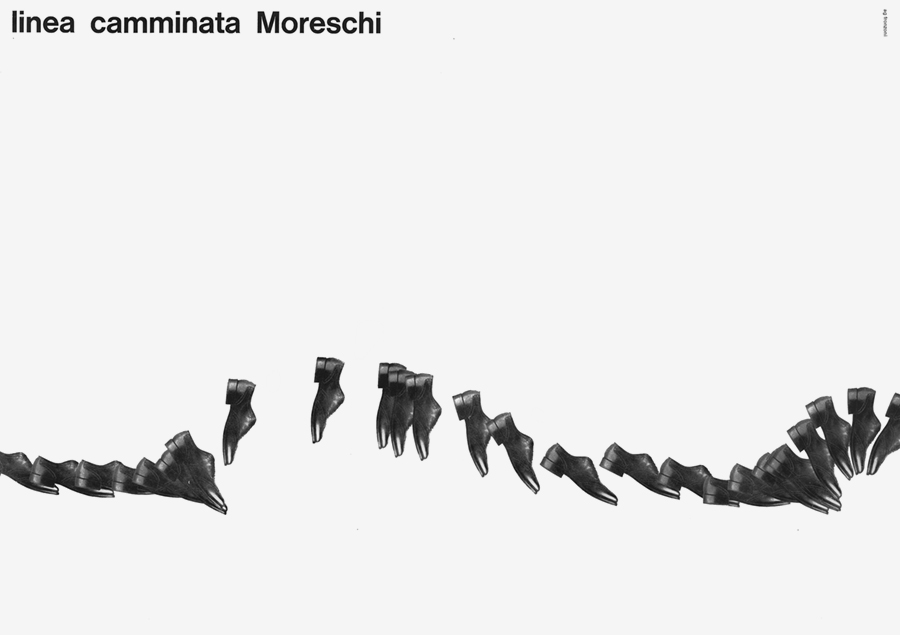

Bold typography

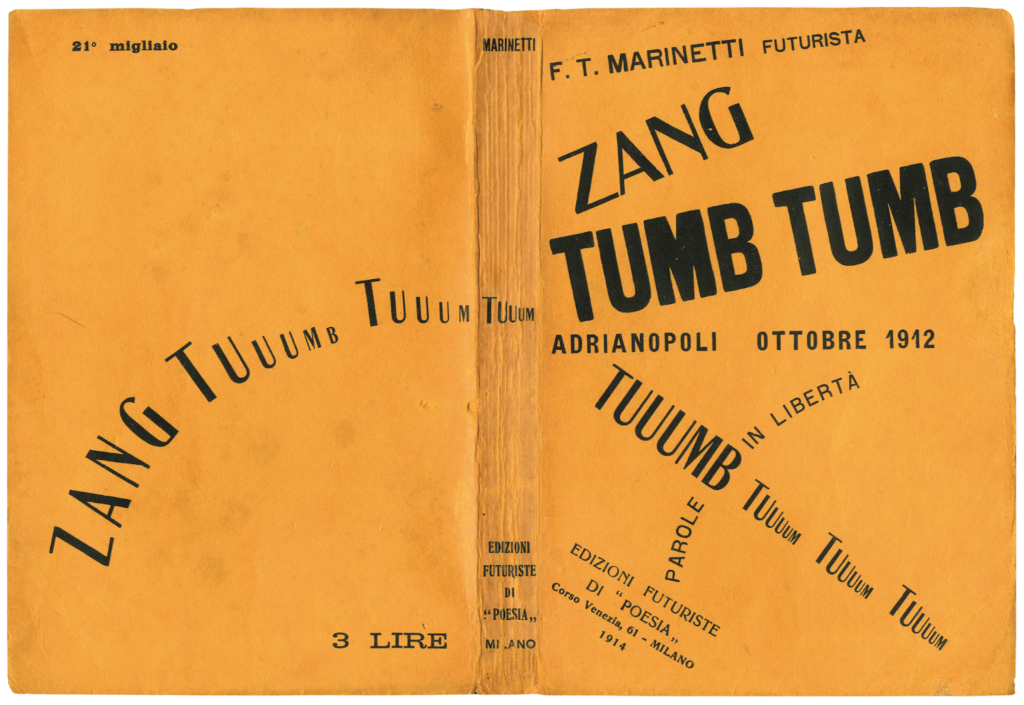

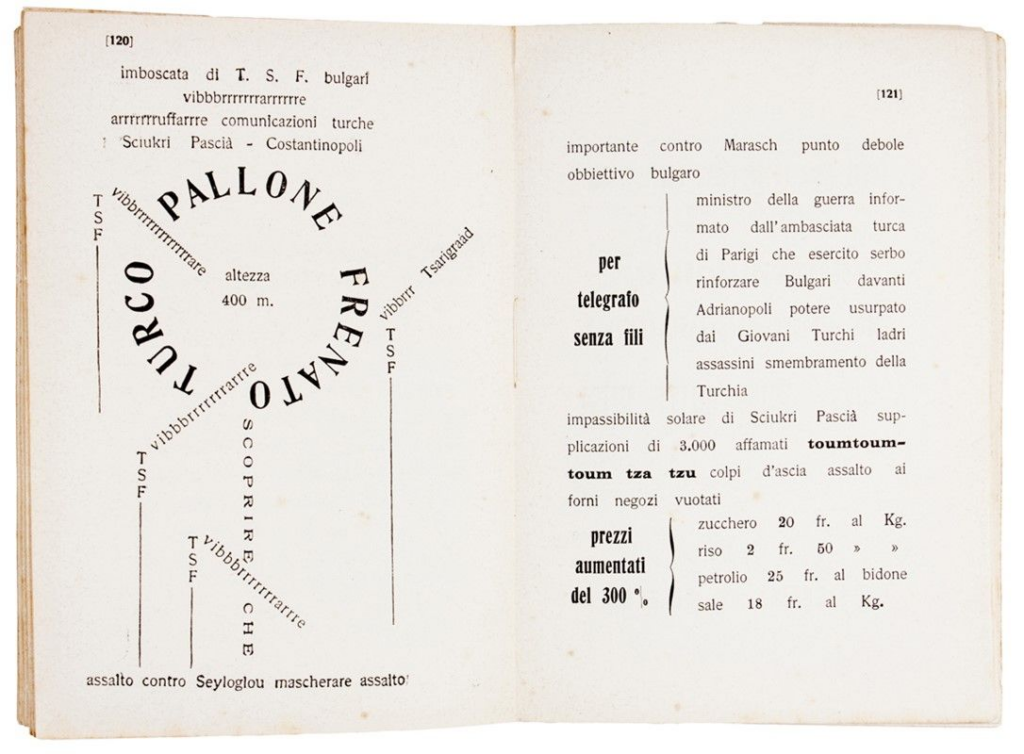

Italian graphic design is characterized by a playful use of typography. Filippo Marinetti’s 1914 book ‘Zang Tumb Tumb’ is famous for its provocative and disruptive type on its cover, derivative of traditional woodcut illustrations from the late 15th and 16th centuries. While Italian woodcut typography paved the way for italic typefaces, golden age designers favored sans-serif typefaces like Helvetica. Nowadays direction and visual weight remain distinctive of Italian typography.

The Futurism, Art Deco, and Rationalism effects

From signage and packaging to advertising, Italy’s graphic design heritage echoes influence from the Futurism, Art Deco, and Rationalism movements.

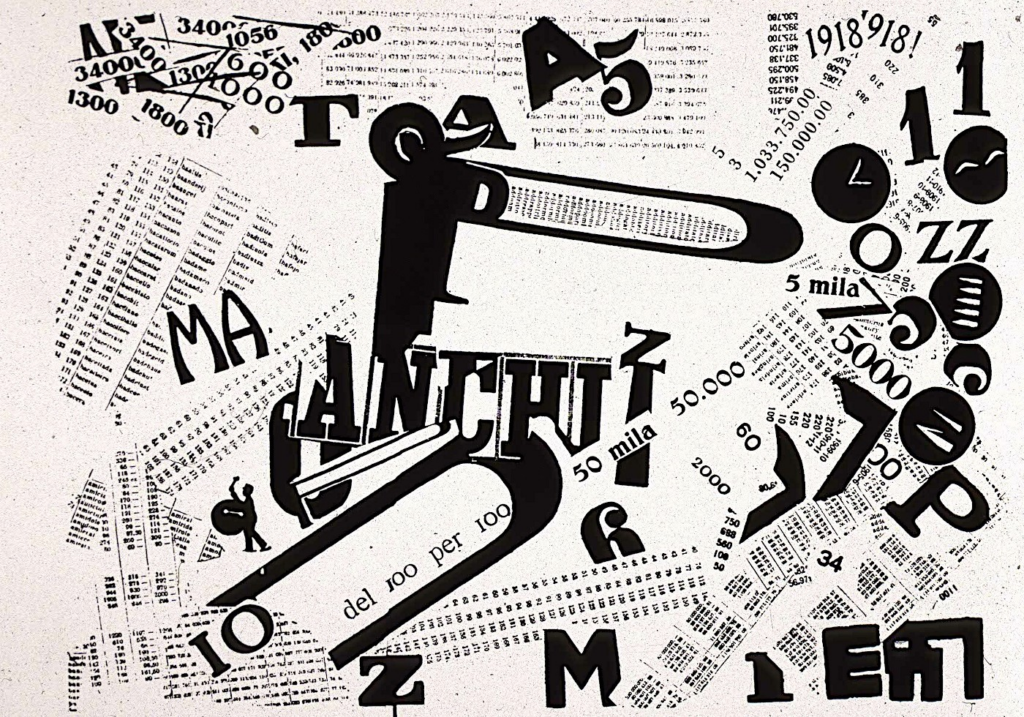

Early 20th-century Futurism put an emphasis on technology, violence, speed, and youth seen in unconventional typography, original hand-drawn rectilinear compositions, and bold colors to express the energy of the era.

Art Deco’s explosion between the 1920s and 30s came next, fusing natural and machine-based elements like geometric shapes, color combinations, and opulent elements that gave that quintessential luxurious feel.

As a response, Rationalism emphasized the rigor of functionality, minimalism, logic, and clarity reflecting the social and political values of the time.

These movements still hold effect in present-day visual communication, not just in Italy, but across the global contemporary design scene. The sum of these movements carry their impression in hallmark Italian design resulting in a distinct visual identity that honors its past, yet, speaks to forward-thinking minds of the 21st century.

A string of emotions

High sensory experiences are not only inherent to the country’s way of life, but it can also be identified in Italy’s graphic design’s golden era through daring colors, directional layouts, multi dynamic use of graphics, stylized elements, and an overall unruly attitude in experimentation. The golden age bolstered Italy’s design identity reaching as far as the Atlantic in a post-war creative exchange with American and German designers.

Who’s Who in Italian Graphic Design

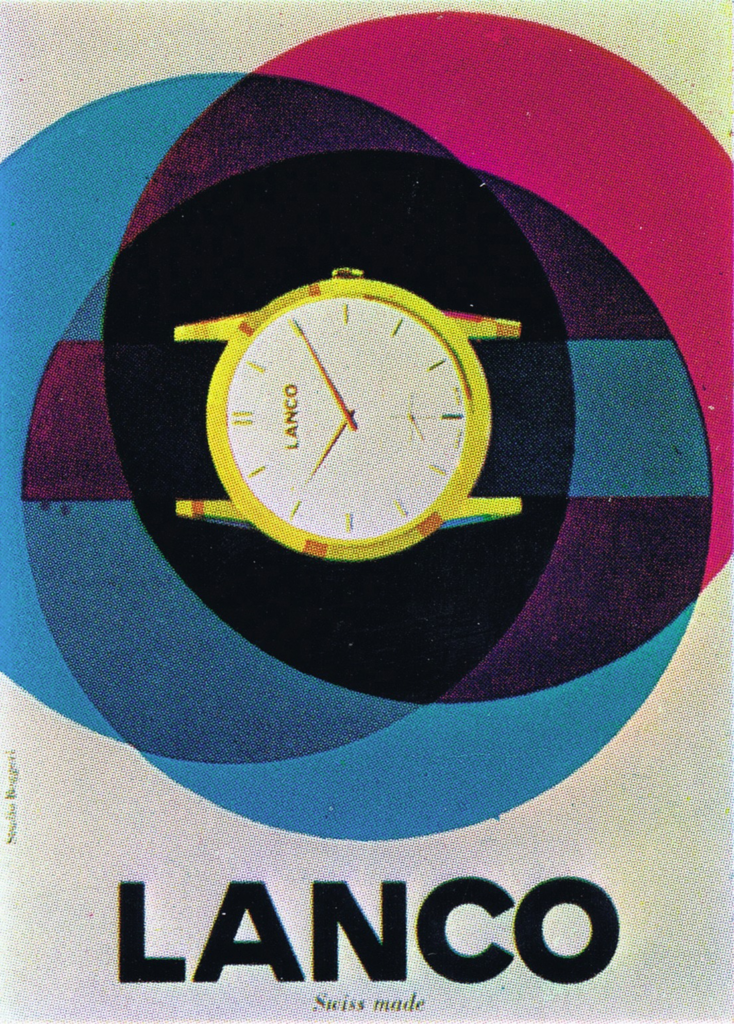

Founded in 1933 by Antonio Boggeri in Milan, Studio Boggeri promoted modernist aesthetics through simplicity, functionality, and a clear visual hierarchy. Its founding served as a pinnacle in the history of graphic design, connecting Italian, German and Swiss talent with American-inspired advertising practices into modern principles of visual communications.

Specializing in commercial graphics, from catalogs, posters, ads, and logos, the studio integrated innovative printing processes and practical, collaborative efforts in creative execution, streamlining their workflow from client concept to final completion.

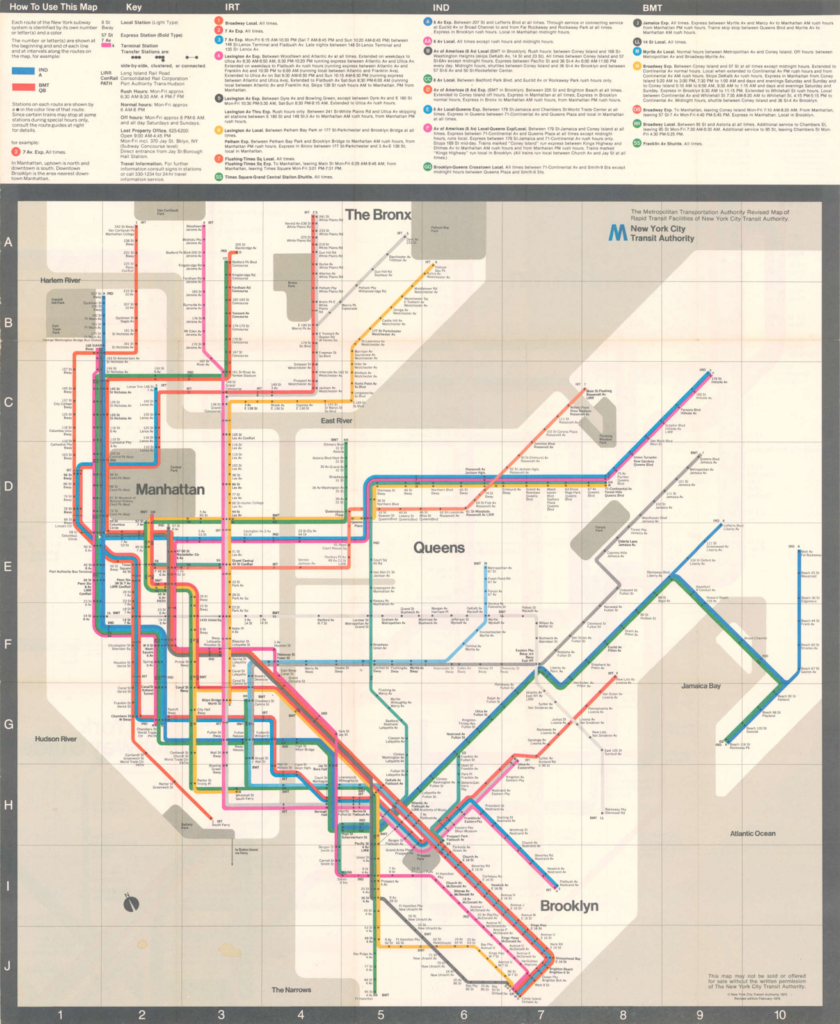

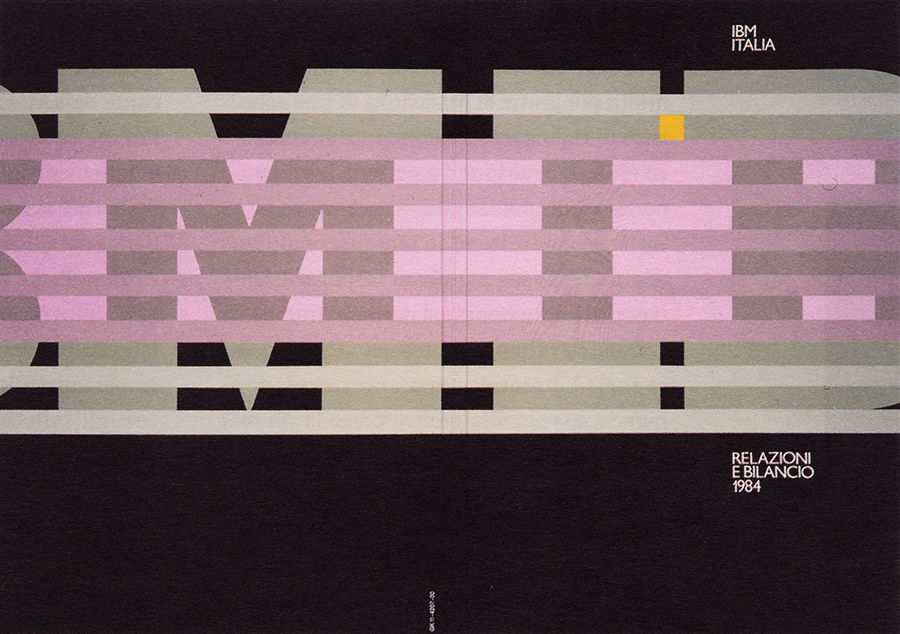

Massimo Vignelli worked within the modernist tradition that emphasized the elegance and simplicity of basic geometric shapes. His work featured the use of geometric abstraction often synthesized in a restrained color scheme of black, white, and red. Vignelli gained undisputed visibility upon his move to the United States with his controversial 1972 design of the New York Subway Map.

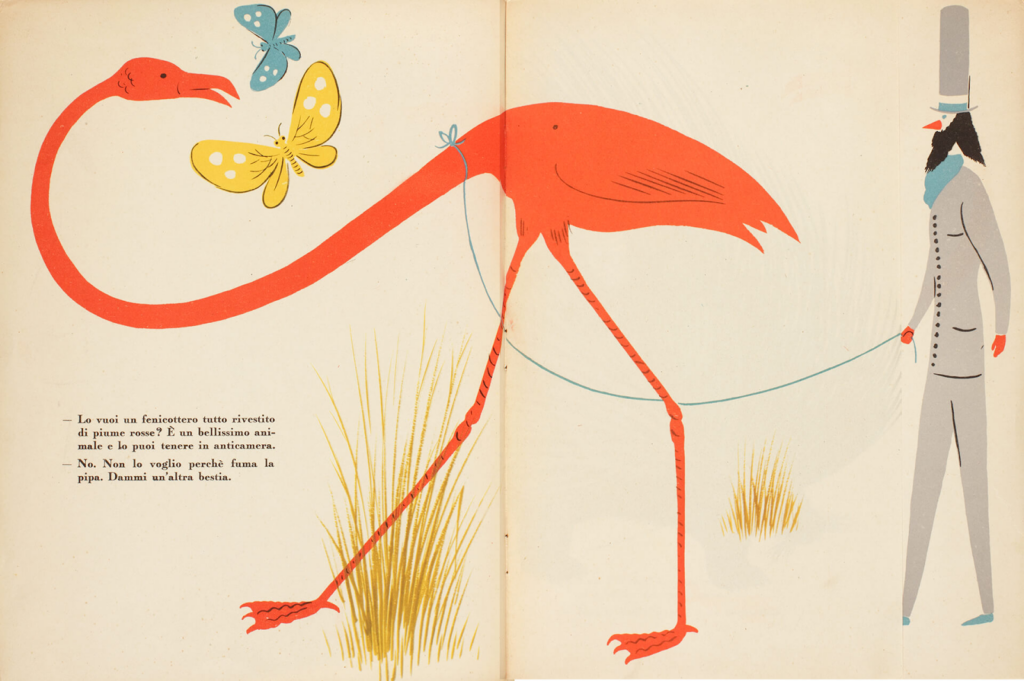

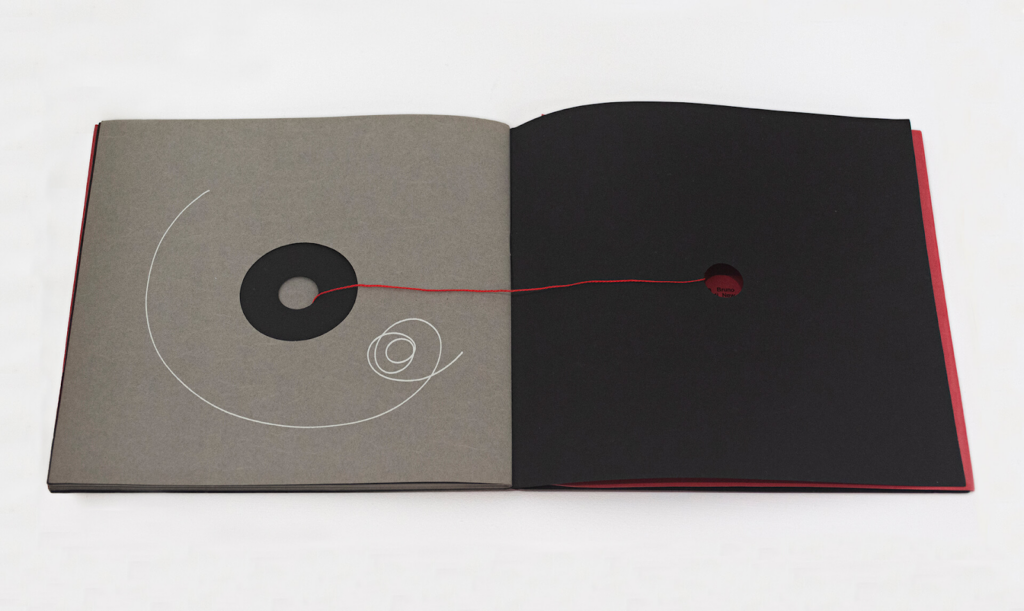

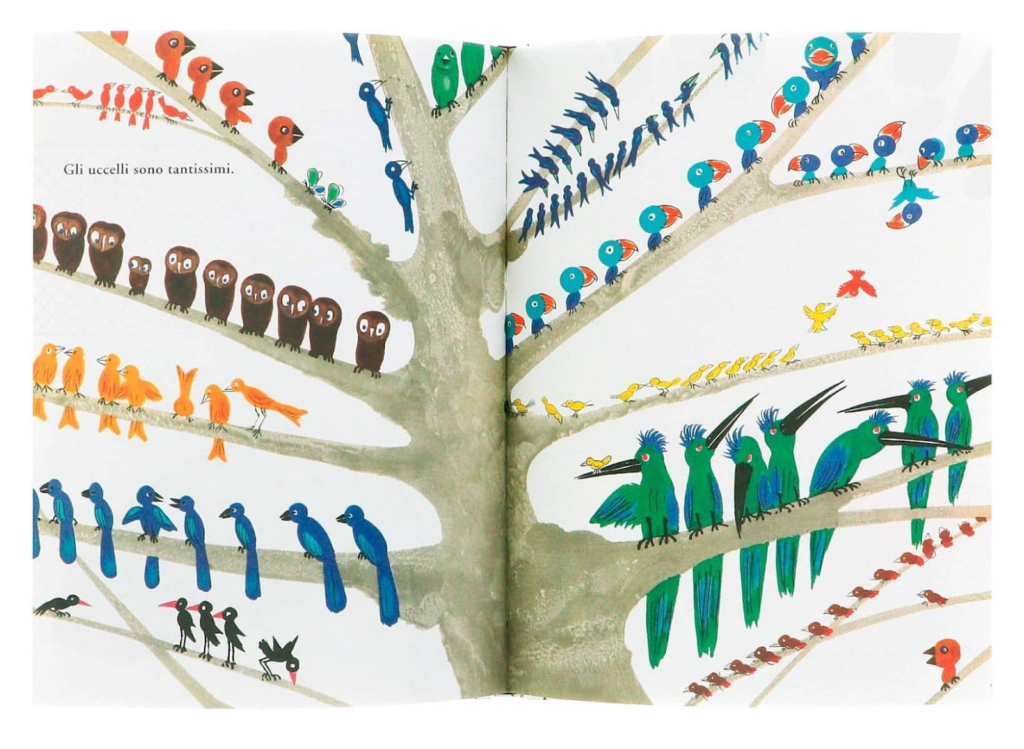

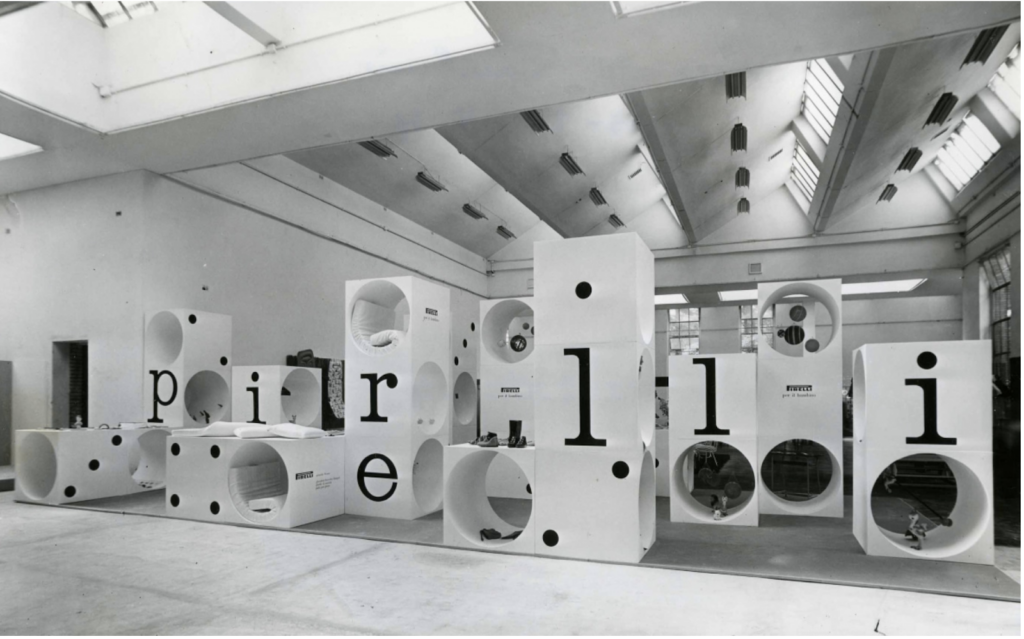

Bruno Munari is considered one of the greatest Italian visual artists of the 20th century. His work is best characterized by its rigorous user-centered approach, abstraction, narrative, modularity, and an omnipresent playful spirit. Often incorporating elements of futurism, surrealism, modernism, and Dadaism, Munari’s work emphasized the importance of the creative process itself, encouraging exploration, experimentation, and a hands-on approach to design. Among his most influential works are his vast contributions to children’s books with pop-ups, cut-outs, and textures that invited kids to play, discover, and see the world through a different lens.

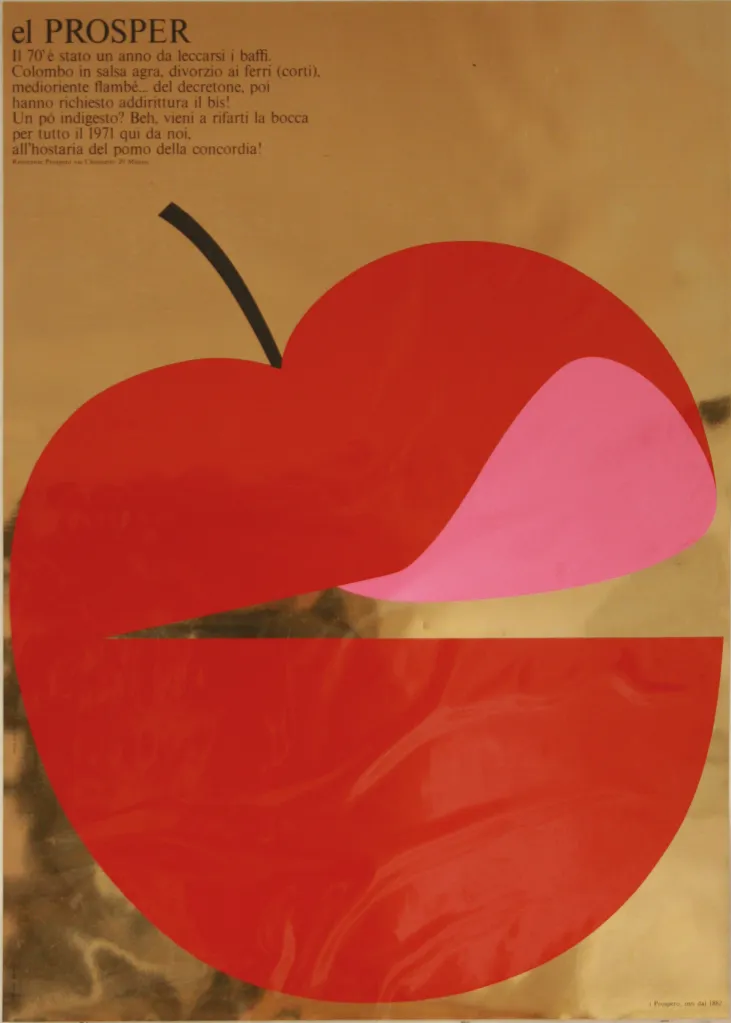

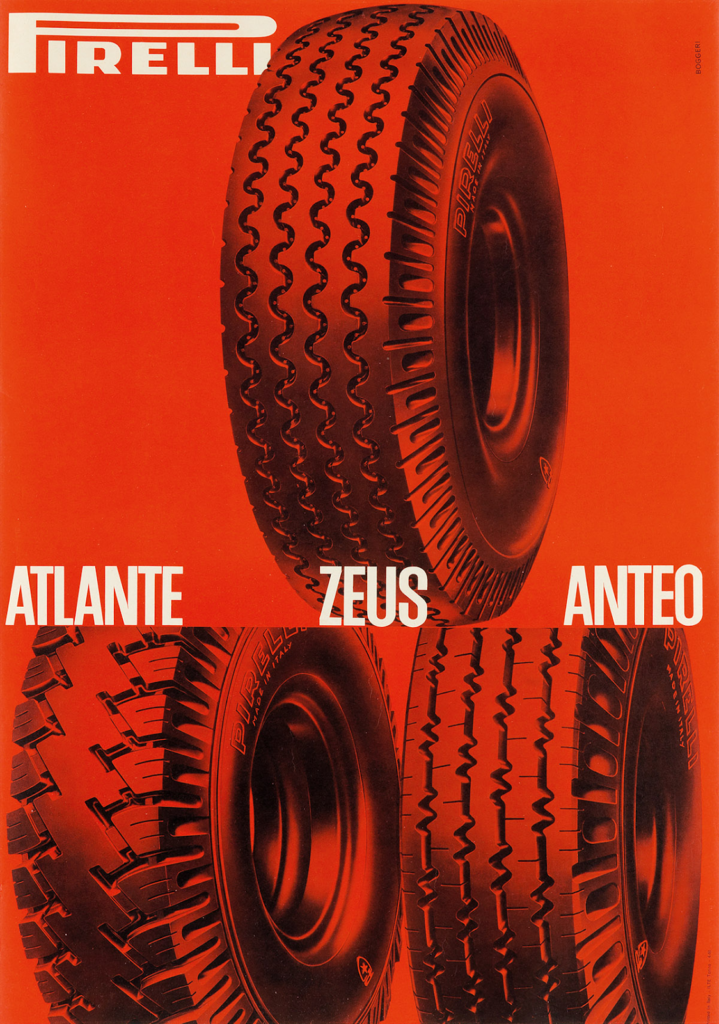

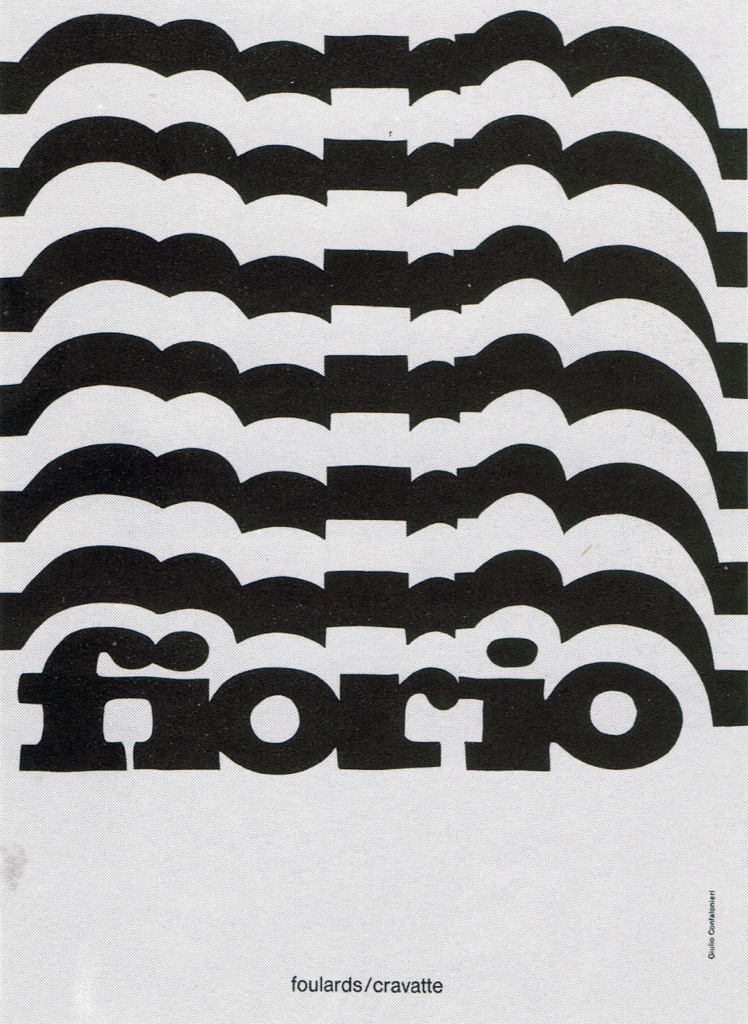

Milanese-born Giulio Confalonieri believed in high-impact graphic design. As one of the key representatives of the Swiss Style of Italy’s graphic design in the 1950s, Confalonieri worked in the fields of editorial, advertising and corporate graphics.

His work is characterized by grid systems and dynamic compositions of contrasting positive and negative tension as seen in typography and stylized elements.

His most notable contributions to the world of graphics include advertising posters for Pirelli and the Triennale.

Internationally acclaimed graphic designer and writer, Italo Lupi is best known for his corporate identity work, exhibition design, as well as posters for international exhibitions.

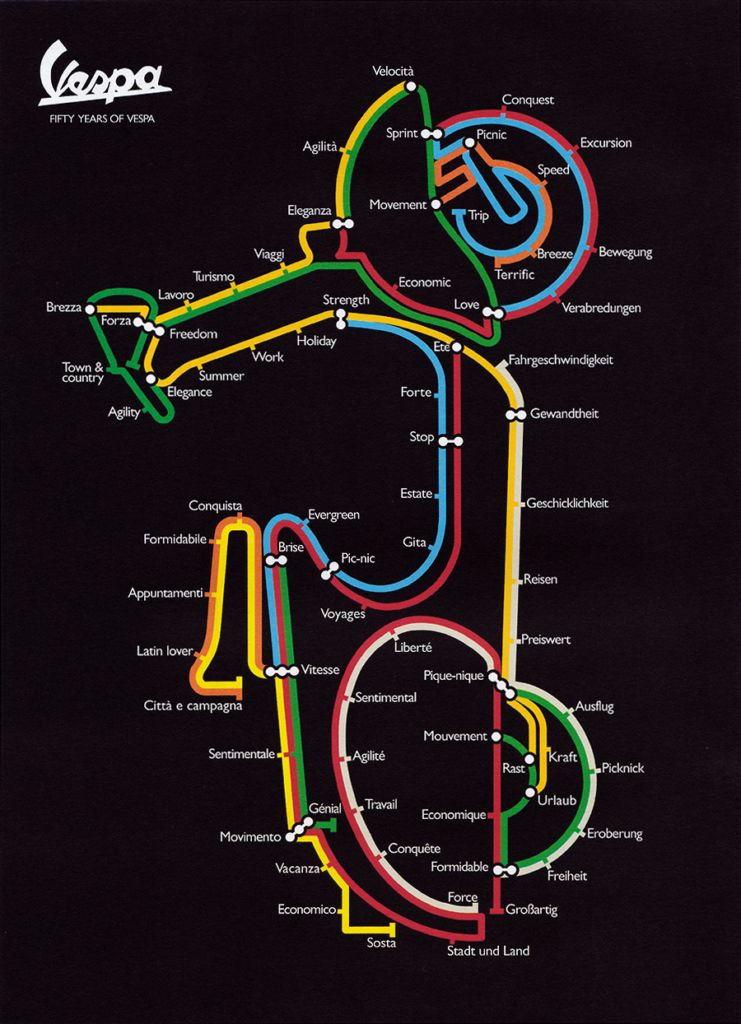

Among his most notable clients are Miu Miu, Fiorucci, Tokyo Design Centre, Cassina, Flos, Prada, and Vespa, as well as his creations for Turin’s 2006 Winter Olympics. Repetition, simplicity, intention, subtraction and flexibility are fundamentals in the distinctive style that made him stand out.

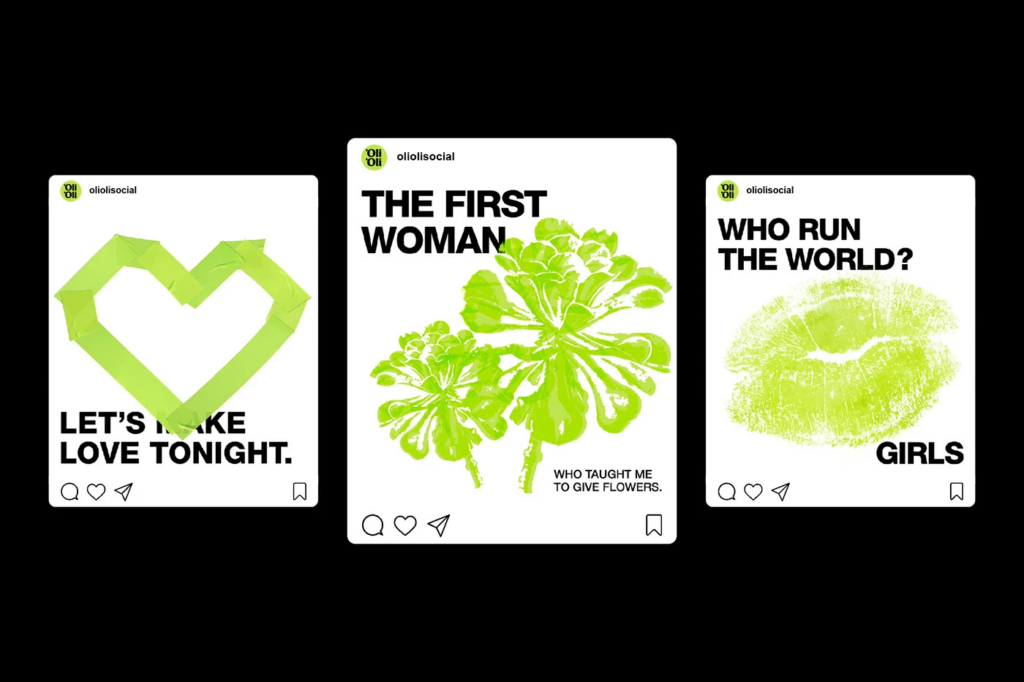

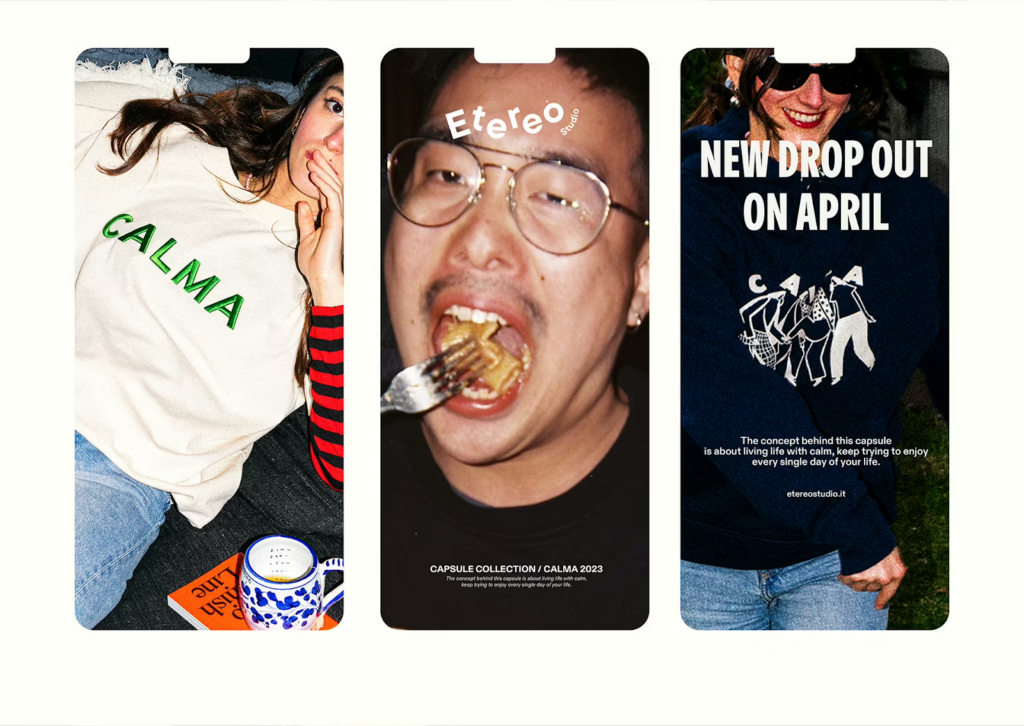

The Ones to Watch

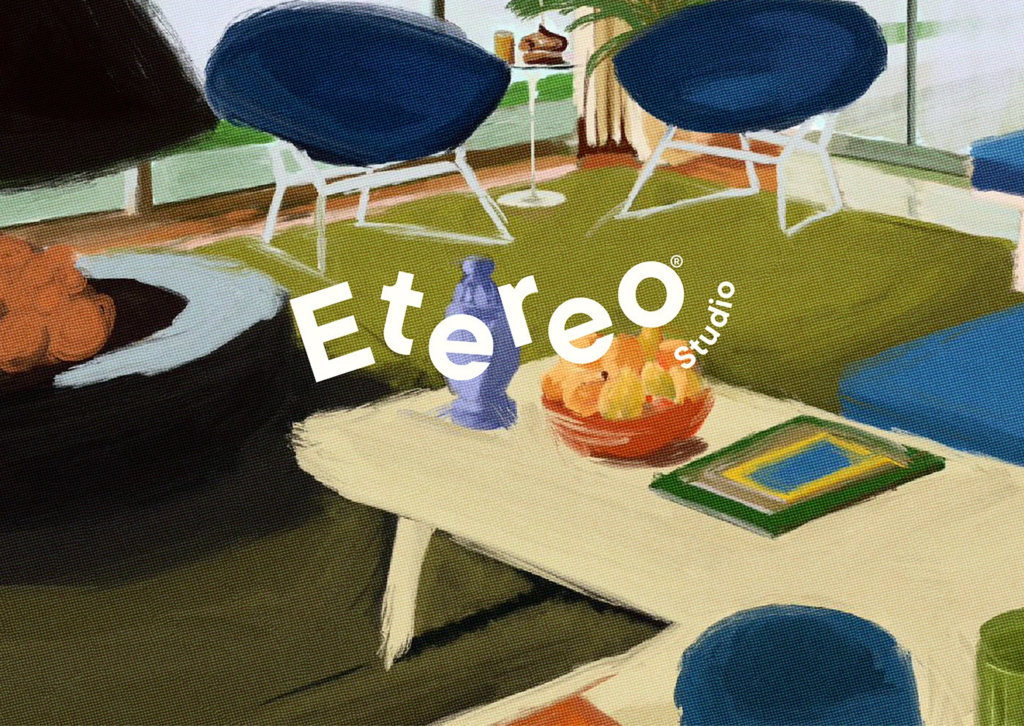

OSMO is a strategy and design studio based in Brescia, Italy. Their work explores the emotional weight of context, clarity, and good old-fashioned intuition in design.

Methodological and intentional, OSMO’s 360-approach recognizes the evolutive nature of our surroundings and thus emphasizes the need for modularity in strategy, branding, product, and experiential design.

Much like firms before them, simplicity meets flexibility through their use of geometrical forms, meticulous abstraction, and repetition.

Based in the heart of Milan, Velvele Studio blends smart design and modern digital solutions informed by the simplicity of Italian culture. The studio focuses on community-building projects, from restaurants to social clubs, aimed at connecting with audiences through co-creative DIY experiences and emotional world-building for maximum impact.

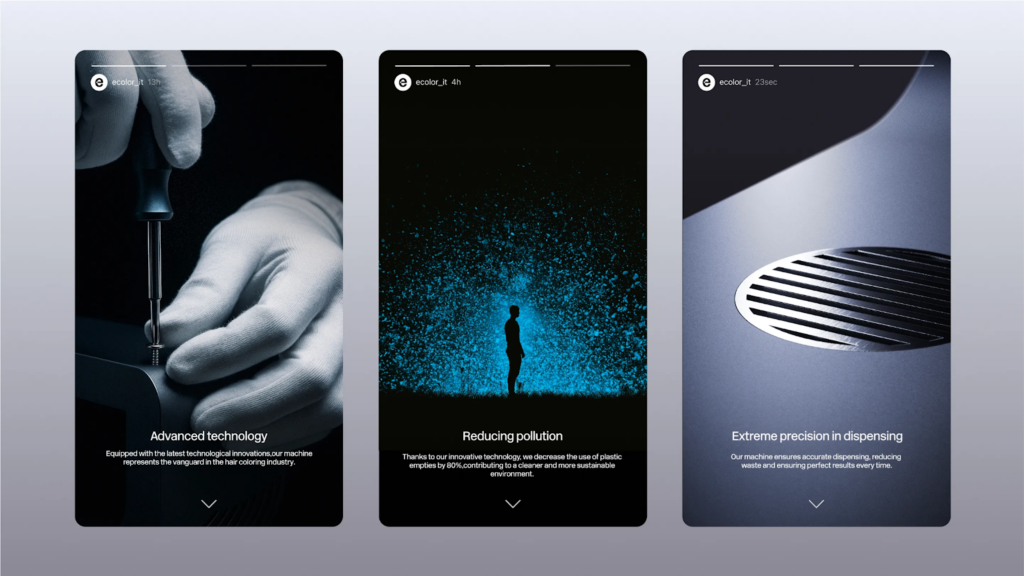

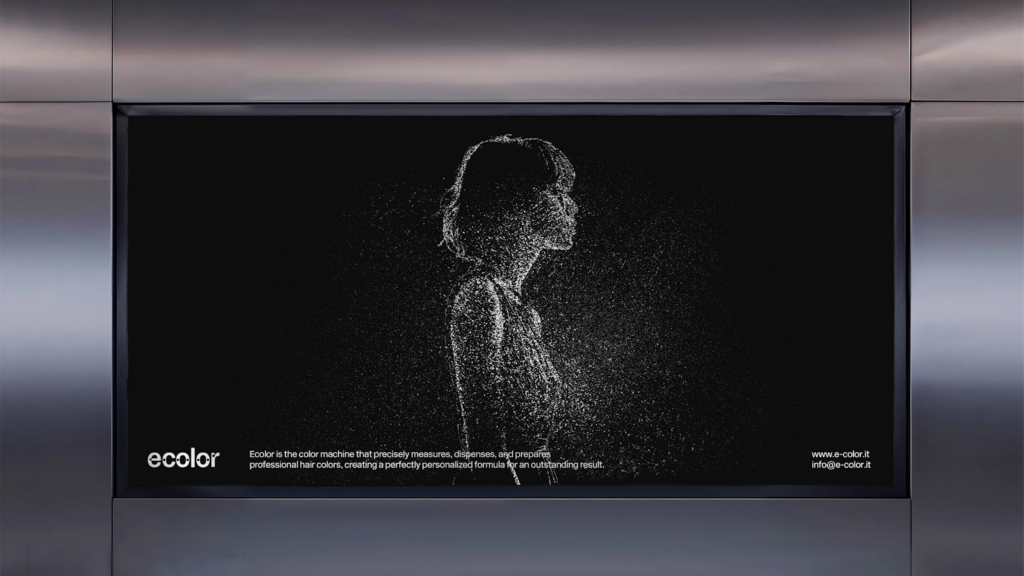

Unfollow advertising is a creative advertising and design agency with offices across Italy. Rooted in a unique blend of innovation and defiance, Unfollow hones in on impactful cultural currency, unconventional digital solutions, and a cool dose of underground flair to bring advertising, art direction, production, and graphic design visions to life.

Based in Reggio Emilia, Nitwix Studio is an Italian marketing agency that combines strategy, aesthetics, and a unique forward-looking view on empathy to bring brands closer to their audiences. Through digital marketing, web, and brand design, Nitwix Studio approaches projects with stylized elements, studied type harmony, and a smart use of color that echoes the simplicity and emotion-led energy of its predecessors. Their projects embrace an interesting synergy between the past, present, and future resulting in a dynamic interplay of timeless, real-life identities and online brand worlds.

Multiverse Studio is known for its experimental and multidisciplinary approach to design. The Salerno-based creative agency blends different fields and perspectives into brand identity, packaging, and digital design, as well as 3D design, art direction, and motion. Recognized for its innovative projects, Multiverse Studio won a Pentawards Platinum award for their project ‘Hera nei Campi’ in the food and beverage design category.

Everyday Objects As The Sum Of A Culture

Design is an ubiquitous element of Italian daily life—a visual language anchored in inescapable confidence, a long standing connection with tradition, and an enviable ease that continues to resonate in today’s modern landscape.

Thanks to an innate aesthetic sensibility and a greater production speed that developed during wartime, post-war Italian designers addressed a broader appreciation for beauty, craft, and engineering in the realms of furniture, lighting, textiles, decorative arts, and automotive design.

Italian Product Design

A fundamental chapter of a larger visual narrative, Italian product design traces the significance of serving both the practical and symbolic functions of everyday objects through form, detail, and color.

During the golden age, design became a means to rebuild and redefine Italy’s identity. Classic aesthetics, modernist principles, and post-war optimism brought together generations of local artisans, manufacturers, and designers in the latter half of the 20th century.

Italian designers honored their artistic heritage and, together with regional craftsmen, devised innovative applications of traditional, locally-sourced materials, like terracotta and marble.

Artisans experimented with newer materials, like fiberglass, plastics, and laminates, and manufacturers developed localized production processes that lead to more affordable, mass-produced objects.

Today, timeless elegance, cultural meaning, and artistic authorship keep contributing to the vibrant tapestry of Italian product design.

Characteristics of Italian Products

Made in Italy

Italy’s design identity is highly associated with quality, craftsmanship, durability, and innovation. Conceived during the rise of consumer culture of the late 20th century, the coveted Made in Italy mark certifies the origin and quality of Italian products—from design and manufacturing to packaging—allowing them to retain their power without overexposure.

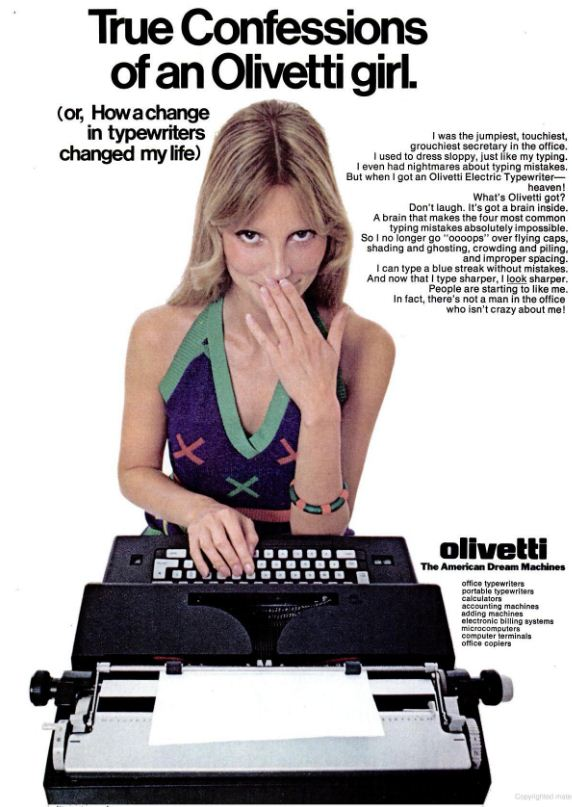

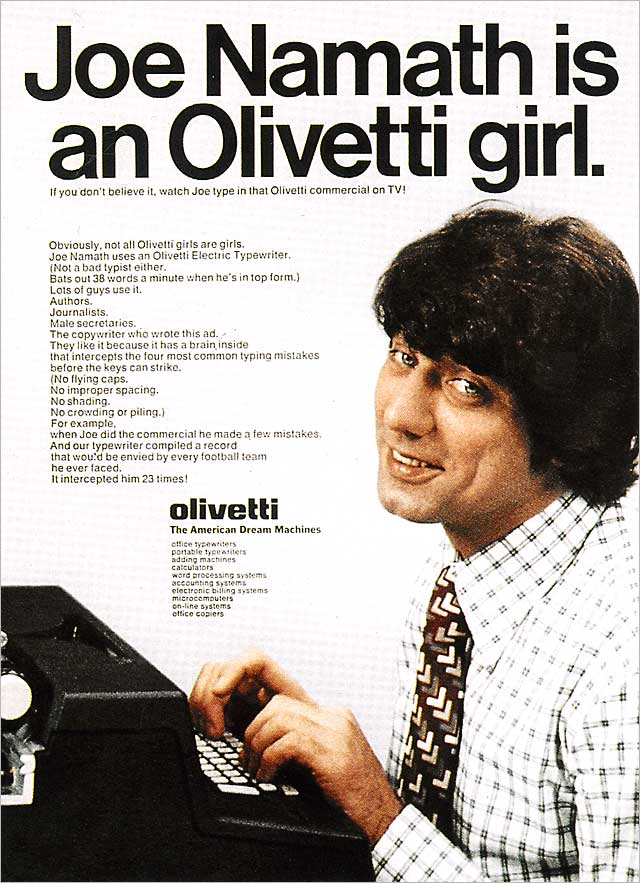

Widely used between the 1950s and 1960s across fashion, furniture, food, and mechanical engineering, the Made in Italy label reached its peak in the 1980s when brands like Gucci, Vespa, Ferrari, and Olivetti (among many others) cemented its prestigious cachet across the globe.

The user-centric principle

One of the key reasons why Italian designers stand out from the rest is because they understand that when it comes to designing products, beauty alone is not enough. Their goal is to create sleek products that are not only intuitive and easy to use, but that also enhance the user experience, add meaningful value to daily life, and serve its form and functional purposes within a lived-in space. Factors like ergonomics and accessibility combined with elegant forms and the use of high-quality materials, technology, and meticulous craftsmanship contribute to the longevity and user satisfaction of Italian products.

From Modernism to Anti-Design

Italy’s design practice is expansive. Italian Modernism embraced futurism’s minimalist ethos (clean lines, high-quality craftsmanship, elegant forms). Under the “return to order” ideal, modern design broke away from tradition and, instead, championed simplicity in a muted palette, geometric forms, and minimal ornamentation.

By mid-century, Italian Postmodernism embraced a more playful, eclectic, and fragmented approach to design, paving the way to colorful, curvilinear works. With the idea of multiplicity, the highly-expressive and often misunderstood postmodern era adopted elements from different time periods and cultures, integrating various artistic mediums and techniques that were rich in references and meanings.

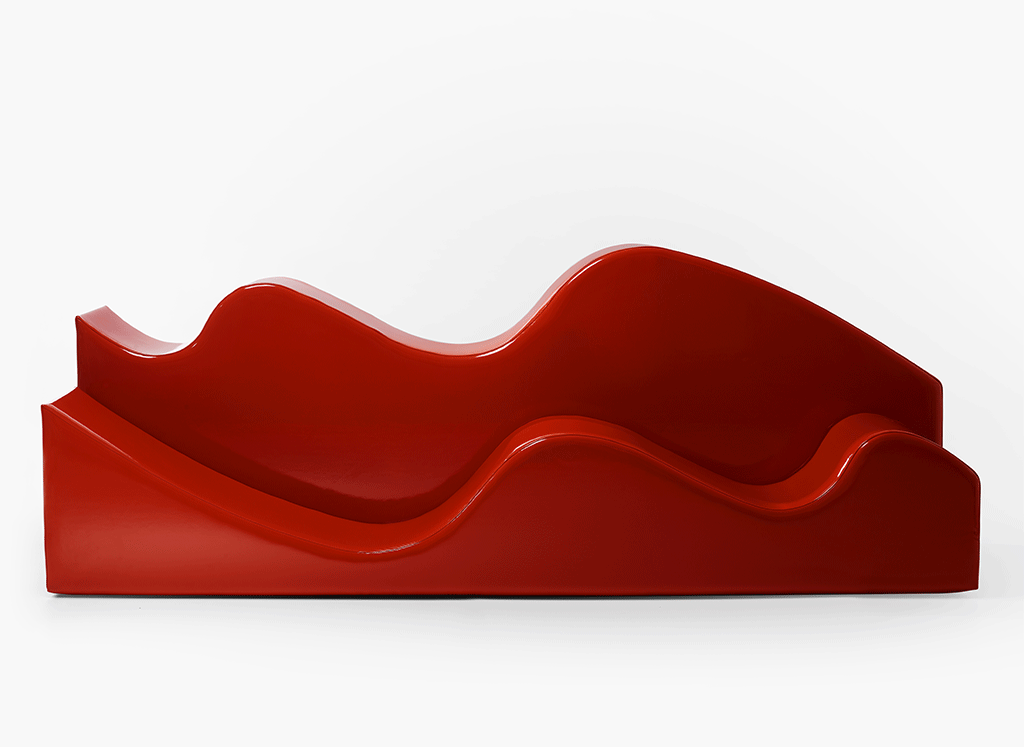

As a reaction against functionalism and the status quo, Italian Radical Design, or Anti-design, from the late 1960s promoted experimental, anti-establishment ideas using design as a tool for social critique.

Instead of preserving the integrity of the material’s properties, Anti-design argued that ‘the perfect form’ that follows a function in an object could never be truly reached. Anti-design is characterized by a playful, egalitarian, and often humorous aesthetic that embraces the exaggerated and expressive qualities that pushes the boundaries of form.

Its legacy shares connections with Italy’s Arte Povera movement, as well as contemporary design trends across fashion, furniture, and architecture as well as graphic design, advertising, and packaging.

The enduring appeal of Italian Mid Century Modern. Integral to developing a modern aesthetic in Europe, Italian mid-century modern designers valued the art of artisanal quality over industrialization.

Even when they worked with new materials or novel ways of engineering, they prized the traditional marriage of materials like ceramics, glass, wood, and marble with sleek organic and geometric lines in dynamic uses of color. Its distinct versatility and timeless appeal have garnered a renewed global appreciation for Italian mid-century modern aesthetics driven by a sense of nostalgia, a growing focus on premium materials and authored designs in favor of a more human-centric approach to living spaces.

Who’s Who in Italian Product Design

Italian architect and product designer, Ettore Sottsass, is best known for founding the Memphis Group, the influential postmodern design collective from the 1980s. Sottsass’s “out-of-the-box” design philosophy poked fun at everyday pieces and turned them into works of art.

Through his work, which included furniture, jewelry, glass, lighting, homeware and office supplies, he challenged the established norms of modernism beyond function, emphasizing emotional experience, accessibility, symbolism, aesthetic and cultural relevance in design.

He drew inspiration from literature, geography, anthropology, and travel, incorporating diverse cultural and historical references into his work.

From modernism to radical postmodernism, Sottsass made significant contributions to the world of design including the portable Valentine Typewriter (1969) for Italian manufacturer Olivetti, the totemic Carlton Room Divider (1981) in his Memphis years, and his beautiful glass and ceramic creations throughout 1947 and 2007.

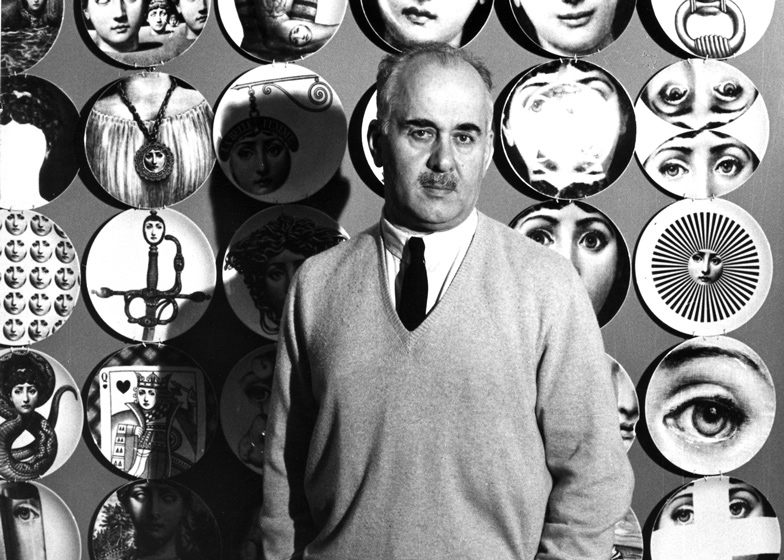

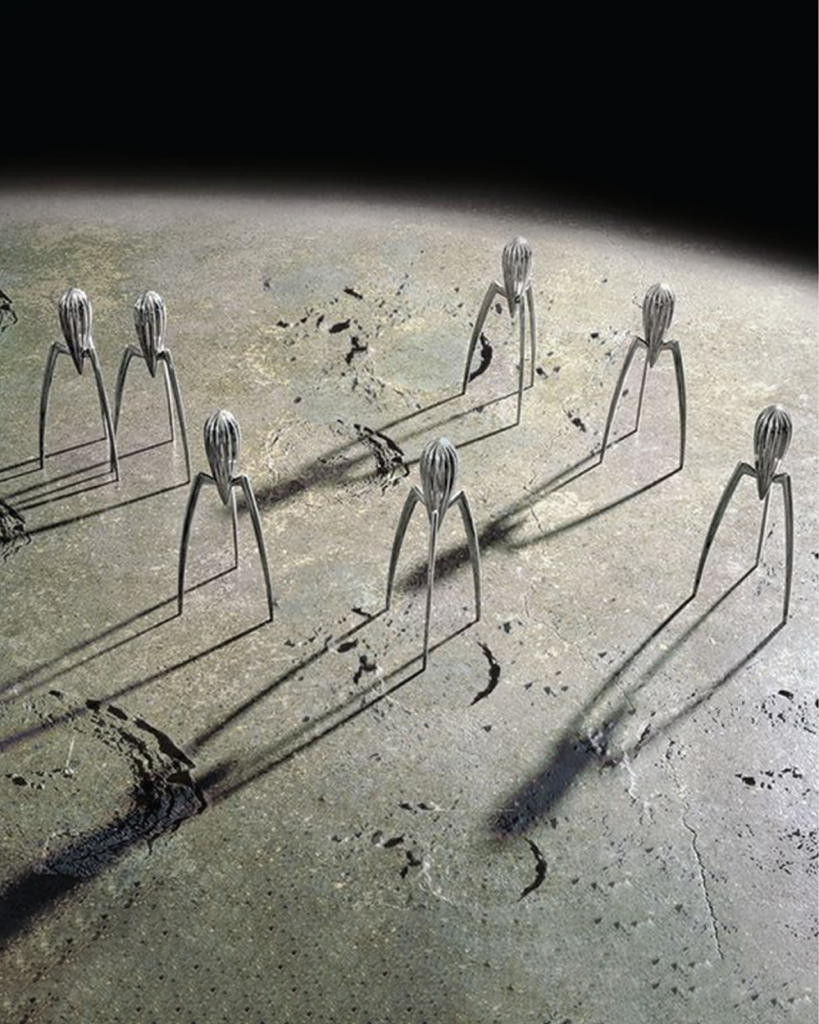

The 1921-founded Italian brand, Alessi, is famous for its diverse range of humorous designs that combine functionality, emotional appeal, and a playful, artistic approach to everyday objects.

From colourful resin details to high-quality stainless steel, Alessi products are not only aesthetically pleasing, but they also excel in purpose and intention. The band’s collaborations with renowned designers and architects have created eye-catching, conversation pieces often reimagining familiar everyday objects in unique and memorable ways.

From Philippe Starck’s squid-inspired Juicy Salif Citrus Juicer (1990) to Alessandro Mendini’s anthropomorphic Anna G. Corkscrew (1994) and Michael Graves’ Whistling Bird Teakettle (1985)—among many, many others—Alessi products blur the lines between functional objects and works of art.

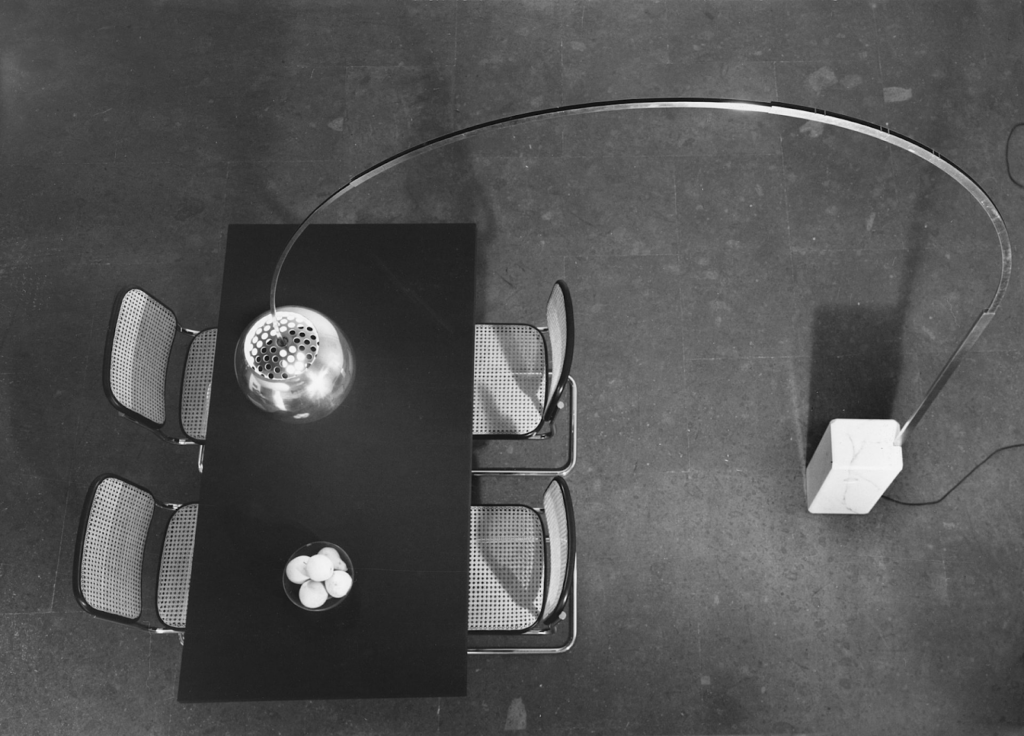

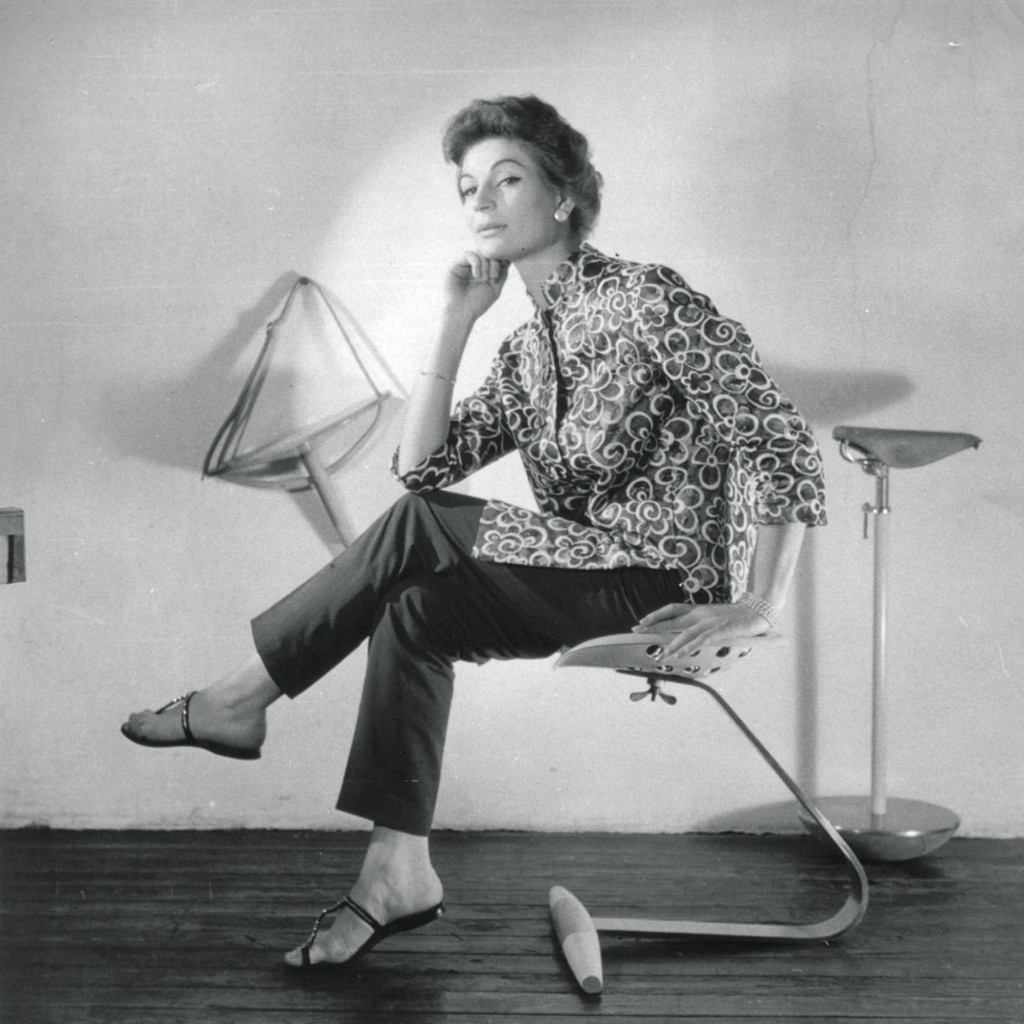

Architect brothers Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni prioritized the practical aspects of design in their practice. As pioneering contributors of Italian industrial design, particularly in lighting and furniture, they dedicated their career to researching new forms, techniques and materials that emphasized problem-solving and user needs. Among their most notable works are the Arco (1962), the Snoopy (1967) and the Taccia lamps (1962), the Spalter vacuum cleaner (1956), and the Mezzadro stool (1957).

Giovanni “Gio” Ponti’s prolific career spans across architecture, furniture, decorative art, and industrial design in a blend of neoclassical and modernist styles. His work emphasizes lightness, fluidity, and a playful use of geometric shapes and colors focusing on creating spaces and objects that enhance the human experience. For instance, his Superleggera chair (1957) for Cassina merits weightlessness, comfort and durability, while the 811 armchair (1957) laid the foundations for sophisticated industrial production with its aesthetic finishing and material efficiency. Ponti also co-founded Domus, the architecture and design magazine founded in 1928.

Afra and Tobia Scarpa are award winning postmodern Italian architecture and design duo who call Venice their home. Their work is informed by functionalism, clean lines, ergonomic organic forms, and the use of natural qualities of materials in innovative blends. Their most notable works include the award-winning Soriana sofa (1969), the Artona chair (1975), and their 30-year collaboration with Italian fashion brand, Benetton.

A symbol of freedom, fashion, and social mobility, the 1946 Vespa—or “wasp” in Italian—designed by Corradino D’Ascanio for Piaggio provided a popular mode of transportation for both men and women in postwar Italy and beyond.

Widely recognized as an icon of Italian design, culture, and ingenuity, the two-wheel motor bike became the perfect accessory among the youth. Its design is characterized by a streamlined, aerodynamic shape, compact bodywork, and engine efficiency making it a hallmark for modern scooters. The Vespa contributed to the rise and creation of consumer culture. Special partnerships and film features throughout the years combine its timeless elegance and carefree spirit to perfection.

The Ones to Watch

CC-Tapis is a contemporary rug company founded in 2011 and based in Milan. Their bespoke, hand-knotted creations combine an imaginative approach to fusing high-quality raw materials (like Himalayan wool, pure silk and linen), modern technology, and centuries-old craftsmanship traditions.

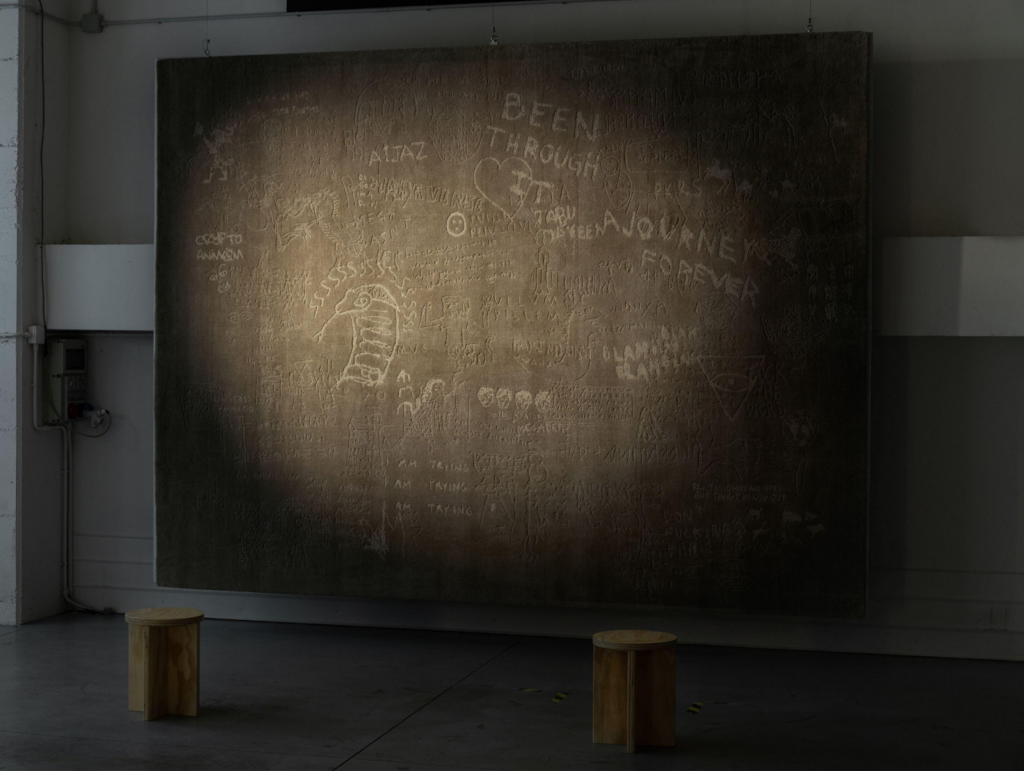

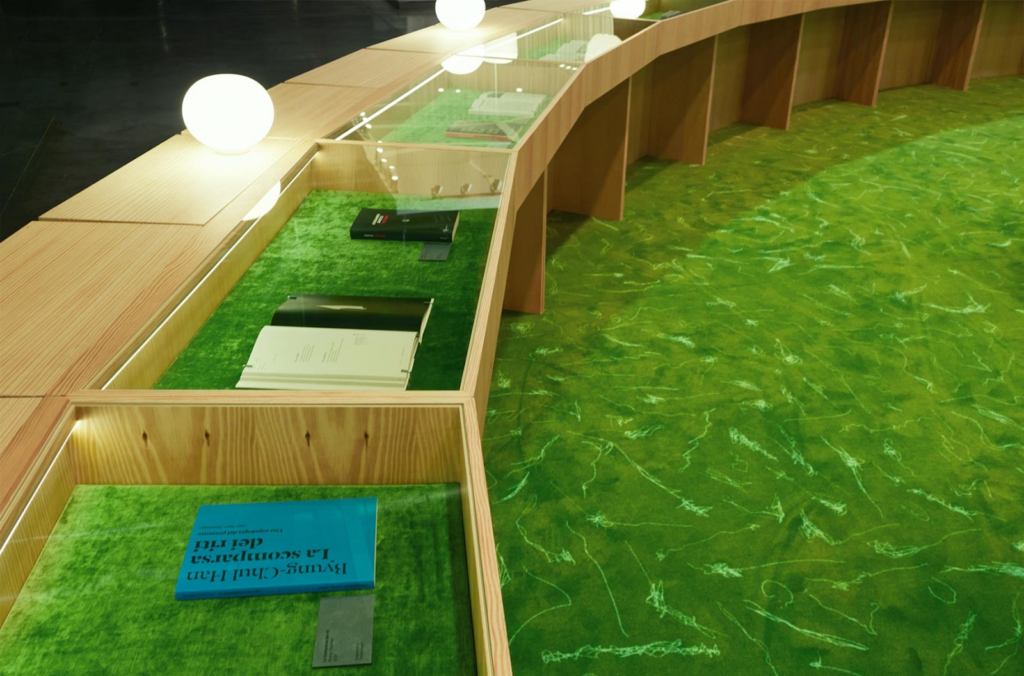

Their 2025 debut at Milan Design Week was highlighted by two main events: ‘Ways of Seeing’ an in-showroom 11-piece exhibition, curated by Giga Design Studio, that focused on the relationship between technology and craftsmanship, and ‘Hypercode’ a collaboration with Italian designer Roberto Sironi, showcasing a collection of handwoven rugs exploring the idea of signs—mythological symbols, ancient carvings, and urban graffiti—as a universal language.

Roman-born product and interior designer, Federica Elmo considers human-made creations as expressions of genius. Her work explores the relationship between contrast, weight, and of course, form and function.

Elmo’s use of chrome, marble, and other overlooked resources embody elevated wavy and conical silhouettes in expressive compositions of textures and color inspired by water and sea life.

Among her notable projects is ‘ONDAMARMO’, an award-winning 6-piece series where she developed a pioneering 3D inkjet printing technique with liquid paint that gave life to an XL-size dining table, two smaller tables, three shelves, and a tray, picking up where her ‘Onda’ metal tables from 2017 left off.

Located between Milan and Rotterdam, design studio FormaFantasma is driven by an in-depth research into the social, cultural, and environmental contexts of design, and its role in shaping personal identity and collective memory.

Founded in 2009 by Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin, FormaFantasma’s work strives for a balance between tradition and modernity, often incorporating elements of both industrial production and craftsmanship.

Projects like ‘Ore Streams’ (focusing on the recycling of electronic waste) and ‘ExCinere’ (using volcanic lava as a building material) demonstrate the studio’s environmental commitment in the legacy of industrial production.

In 2024, FormaFantasma played a significant role during the Salone del Mobile, transforming Euroluce—the biennial lighting trade fair—into Drafting Futures Conversations about Next Perspectives, a space and venue for talks and roundtables curated by Annalisa Rosso.

Valerio Sommella is an Industrial designer from Tuscany. His practice dives deep into the unique language of objects in an ongoing dialogue between form, context, material, and technology resulting in a recognizable aesthetic.

Versatile and nuanced, Somella’s work ranges from mass-produced items to smaller, more intimate series. His most regarded pieces include the twisted, chrome-finish stainless steel Sfrido peeler for Alessi, the aluminum Sorrento three-prong lamp for Nava, and the Eight Reserve Bottle for 818 Añejo Tequila. In 2025, Sommella presented the Portofino lamp during the 2025 edition of Milan Design Week—the annual global event that celebrates furniture, design, and innovation.

IAMMI is a Milan-based creative design studio founded by Nicolau dos Santos and Stephanie Blanchard. The duo prides itself for working directly with artisans, technicians, and suppliers developing pieces that resonate emotionally and inspire reflection.

Their “collectible designs” bridge the gap between traditional and modern aesthetics characterized by a playful use of irony and provocation. Most recently during Milan Design Week 2025 the studio presented SENSES a multisensory installation in partnership with interior design firm materia-studio at the MelzoDodici auditorium in Porta Venezia. Among their most recognizable work is Un Pesce Fuor d’Acqua pouf (2025), Brrrick (2025), and Clouds armchair (2025).

Design As A Public Tool

From Romanesque and Renaissance to Baroque and Modernism, Italy’s continuous transmission of exemplary architecture lives in an ongoing dialogue between patrimony and possibility. Time reveals itself in medieval ironmongery, elegant carvings, eye-catching stone surrounds and streamlined geometry absorbing the rhythm of its inhabitants with an energy that never fades.

Italian Modern & Contemporary Architecture

In architecture, place and perception set the tone for everything that follows. With a high degree of contextual references, Italian modern and contemporary architecture boasts some of the most admired structures in the world.

Spanning the 20th and 21st centuries, Italian modern and contemporary architects led the democratisation of design in Europe marking a radical departure from the ornate styles of the past. This sentiment laid the groundwork for designs that prioritized functionality and the rational use of materials.

The birth of modern architecture in Italy was characterized by technological advancements and minimalist principles reinforced in concrete, cast iron, and plate glass. Such structural robustness of the era met the adaptability of sleek contours in a beautiful contrast against the country’s natural background.

Rationalism, Novecento, and Fascist-era architecture contributed unique elements to Italy’s modern landscape by weaving green spaces into the urban fabric. Asymmetrical designs and neutral color palettes created a sense of dynamism and sophistication.

The melting pot of Italian contemporary architecture combines elements of modernism with a focus on sustainability, innovation, and a more fluid approach to design. Elements from Renaissance, Art Nouveau, and Palladianism co-live in historical elegance with current trends, brought to life by organic elements, such as the use of natural light and handpicked materials like stone, wood, and textured plaster.

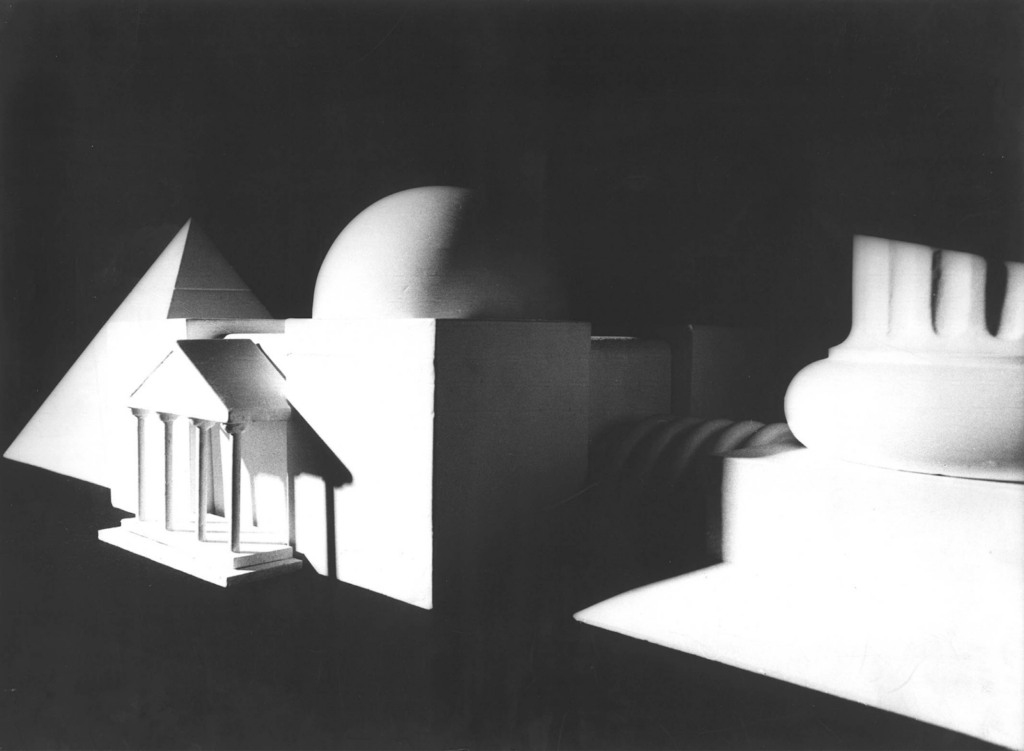

Characteristics of Italian Architecture

Classical influences

With a strong connection to ancient Roman and Greek architecture, Italy’s architecture draws upon classical elements of Renaissance symmetry, proportion, and harmony alongside elaborate Baroque ornamentation, and curvatures. Columns (Doric, Ionic, Corinthian), arches, and domes daringly merge with the grandeur of ornate frescoes, marble sculptures, and gilded facades.

Rococo’s fluidity and grace evolved into a Neoclassical aesthetic which, in turn, moved towards Art Nouveau before Fascism’s heyday, exemplifying the cyclical nature of the country’s storied landscape. Italian architecture also referenced outsider movements such as French Gothic, Byzantine, and Rococo.

Light and space

One of the fundamental principles of Italian architecture is connection. Open floor plans foster a sense of connectivity reflecting Italians’ preference for interaction.

Interconnected living areas embrace a strong link with natural beauty in a seamless indoor-outdoor flow that maximizes both natural light and living space. The result is a warm, inviting atmosphere that exemplifies the lure of traditional Italian hospitality.

Local context

Italian architecture commonly reflects its surrounding environment, climate, and culture in properties built with locally-available natural resources in harmonious color palettes. For instance, in mild and balmy regions such as Tuscany and Umbria, traditional architecture uses terracotta roofs, stone facades, and open courtyards to maximize natural ventilation and light.

In mountainous regions like the Dolomites, architects prioritize sturdy, stone-built structures with sloped roofs that withstand heavy snowfall. This move does not only create a sense of unity and belonging, but also speaks of a seamless integration with the landscape.

Italian villa tradition

In Mediterranean vernacular, Italian villas offer a retreat from the city life and provide an idyllic setting for leisure and relaxation. In Ancient Rome, villas were commissioned by wealthy families as sophisticated status symbols featuring elaborate gardens, terraces, and architectural styles inspired by classical Roman and Greek designs.

Today, villas serve as windows into Italy’s cultural legacy reimagined throughout western European country estates and other parts of the world influenced by European culture.

While varied, Italian villas are characterized by picturesque and asymmetrical designs often featuring a prominent tower, low-pitched roofs, exposed beams, decorative brackets, narrow windows with arched or pedimented tops, elaborate window crowns, and single-story porches or entry porticos.

Who’s Who in Italian Architecture

As key players in the Italian Radical Design movement of the late 1960s and 1970s Archizoom, Superstudio & Studio 65 (Studiosessanta5) questioned the role of design, each exploring utopian visions and experimenting with new forms and materials in their creations.

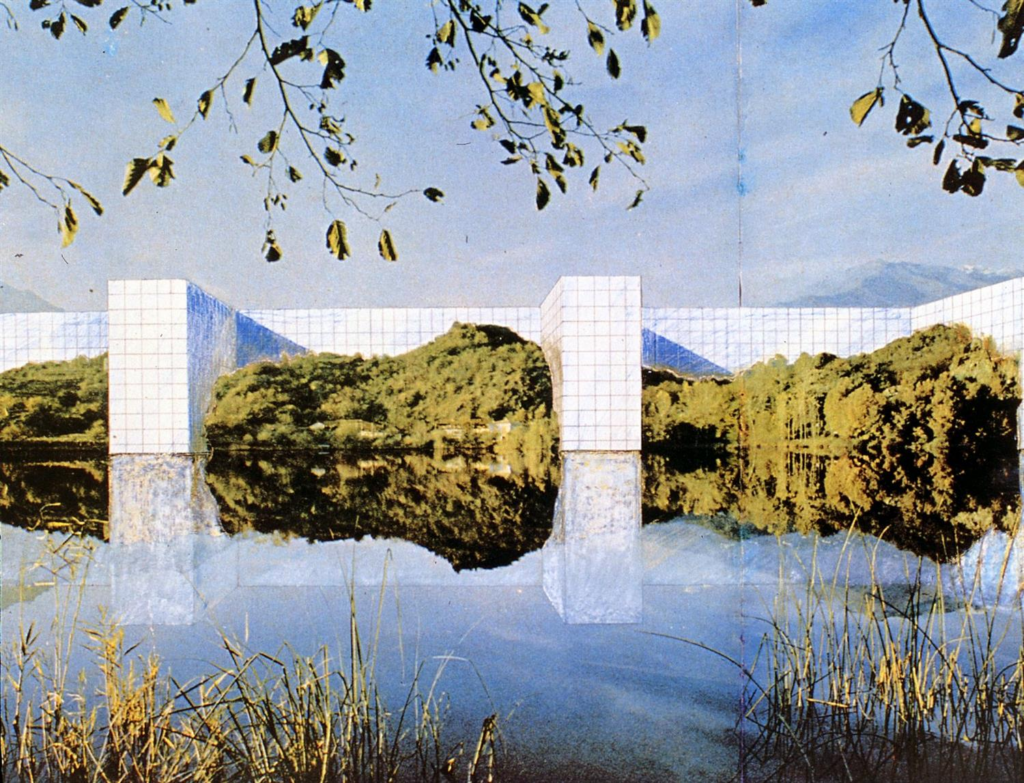

Archizoom Associati was a prominent Florentine architectural and design group known for their radical anti-design approach seamlessly merging architecture and landscape. Their pop-inspired, ironic, and provocative works subverted the principles of functionalism in urban planning with unconventional materials, kitsch elements, and vibrant color choices.

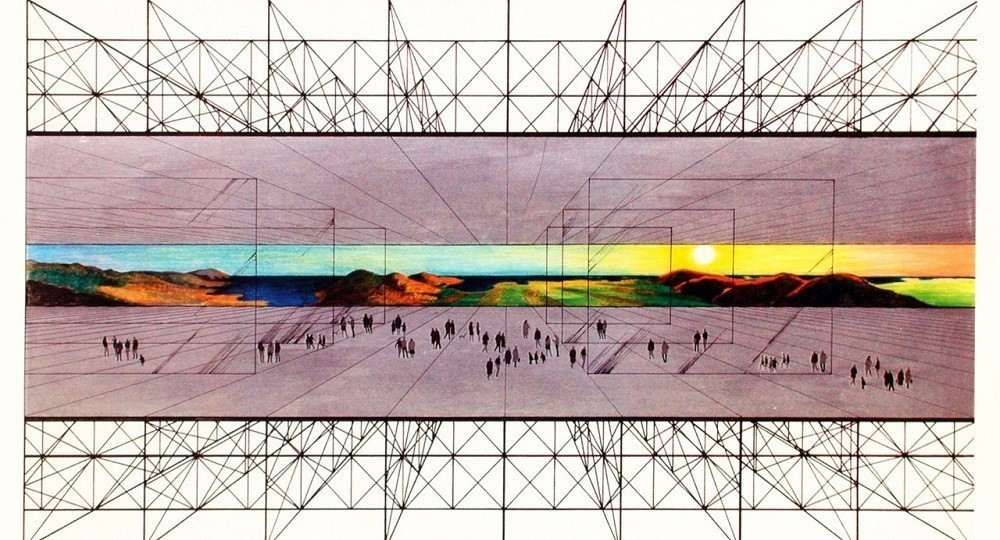

Archizoom often collaborated with Superstudio, the architectural collective whose designs employed photo-collages, films, and exhibitions to critique modernism, consumerism, and the status quo of design and urban planning.

Finally, the avant-garde architectural and design collective, Studio 65, contributed to the radical design movement with works that fostered provocative discussions about the role of design, combining a fun use of form and color with a critical discourse about everyday life.

Milan-born Mario Bellini is an internationally renowned designer, architect, and eight-times winner of the prestigious Compasso d’Oro—the most prestigious Italian design award. His practice explores how people move through space and interact with objects, combining functionality with a sense of visual delight and sophistication.

Bellini’s buildings are designed to be integral parts of their environment, from nature to its surrounding urban context, creating a sense of place and belonging. Among his best architectural creations are the Tokyo Design Center (1991), the 2012 restoration of Palazzo Pepoli in collaboration with graphic designer Italo Lupi, and the Bambole sofa for B&B Italia.

Gaetana “Gae” Emilia Aulenti was an Italian architect and designer known for her innovative and eclecticism in blending functionality with artistic expression. Her practice is characterized by a respect for historical context, a fluid use of materials, and a focus on the relationship between space, object, and user.

Aulenti is renowned for her “adaptive reuse” work in furniture design, museum interiors, and public spaces, such as pieces like the Pipistrello lamp (1965), the interior renovation of the Musée d’Orsay (1980 to 1986), and the prominent multi-sport and landmark exhibition venue, Torino Palavela (2006).

Italian architect and urban planner, Stefano Boeri, is known for integrating greenery into urban environments, particularly through the concept of the Vertical Forest—visions of cities as ecosystems where buildings and green spaces coexist—exemplified by the Bosco Verticale (2014) in Milan.

His multidisciplinary work encompasses architectural design, urban planning, research, and theoretical studies at a global scale.

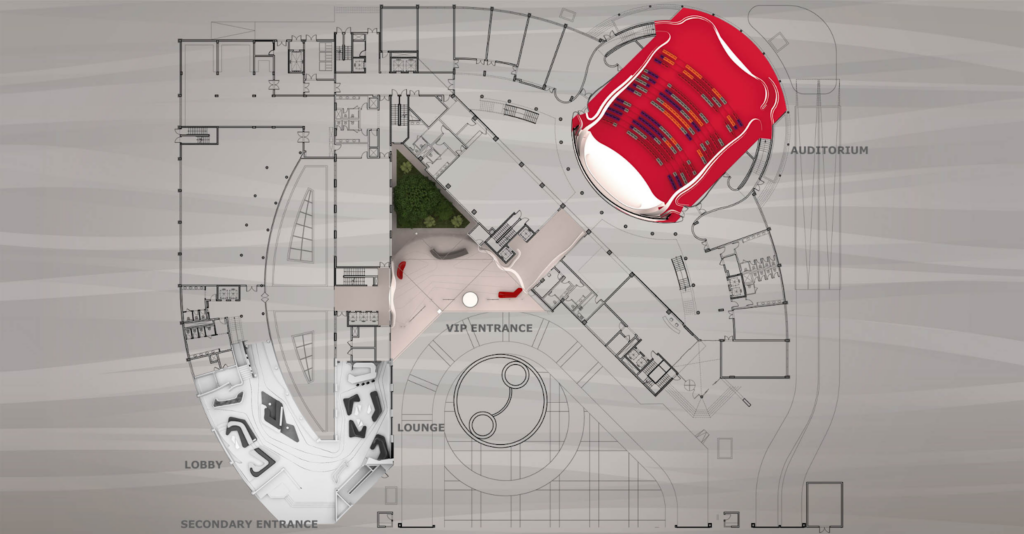

For the Milan-based architect Cino Zucchi, mindful social integration and a strong connection to the urban fabric are integral in his architectural practice. Zucchi is deeply engaged in designing sustainable, fluid, and adaptive spaces, drawing inspiration from historical contexts while creating contemporary solutions for the modern user.

The new headquarters of the Lavazza Group in Turin, was designed by Zucchi based upon the concept of a cloud as a symbol of enlightened thinking. Inaugurated in 2018, the large-scale complex includes spaces dedicated to culture, education and leisure with features like the Lavazza Museum, a restaurant, an event space, and an archaeological area.

The Ones to Watch

Dimorestudio is an Italian architectural and design firm renowned for its distinctive blend of historical and contemporary styles. Their signature approach blends a meticulous selection of materials, contrasting color palettes, and artisanal techniques resulting in dramatic yet inviting spaces. The firm also creates bespoke furniture, lighting, and textiles under Dimoremilano.

From residential spaces to retail boutiques and hotels, Dimorestudio has partnered with fashion houses like Hermès, Bottega Veneta, and Fendi, as well as with hospitality clients like Ian Schrager and Thierry Costes, and immersive exhibitions in collaboration with Loro Piana, Hosoo, and Yves Salomon.

Piuarch is a Milan-based architecture firm founded in 1996 by Francesco Fresa, Germán Fuenmayor, Gino Garbellini, and Monica Tricario, known for their contextual sensibility and human-centered designs.

Their goal is to create spaces that enhance the lives of the people who inhabit them. Committed to sustainable design principles and responsible use of resources, Piuarch brings together diverse backgrounds and perspectives to ensure innovative and dynamic spaces under their authorship.

From corporate offices and retail buildings to residential complexes and urban renewal works, their projects include the award-winning Porta Nuova building (2013), the Gucci Hub headquarters (2016), and Quattro Corti business centre (2010) in St. Petersburg. Piuarch is a regular fixture of the Venice Biennale of Architecture.

Florence-born Giulio Margheri works across architecture, scenography, curation, research and product design whose specialty revolves around the impact of ephemeral spaces on human life and interaction, from temporary installations to interior design and small-scale architecture projects.

Margheri’s practice includes the restoration of the historic building Fondaco dei Tedeschi in Venice, retail and scenography projects for Jacquemus, Prada, and Miu Miu, as well as curation of institutional exhibitions including Recycling Beauty at Fondazione Prada in Milan (2022).

In 2015 he joined the renowned international practice OMA as senior architect, and its research and design studio, AMO, founded by Rem Koolhaas, known for its innovative and often unconventional designs.

The firm Mario Cucinella Architects (MCA) prioritizes the cultural context and the holistic approach to the broader environmental and social impact of each project they’re involved in.

Thanks to a dedicated internal sustainability R&D department, MCA’s practice incorporates “solar carving,” a distinctive principle where building shapes are sculpted based on the sun’s movement, maximizing daylight use and minimizing the need for mechanical cooling.

Some of the firm’s innovative projects include TECLA (2021), the first eco-sustainable house model 3D printed in local raw earth, and MyCityBari (In Progress), a sustainable living complex sculpted to optimize sunlight penetration.

Based in Torino, Italy, Carlo Ratti Associati (CRA) is an international design and innovation office recognized for blending natural and artificial elements through digital technologies and sustainable architecture.

CRA’s work spans from furniture to building design and urban planning, with a strong emphasis on sustainability and circular economy principles looking to fully immerse those who come in contact with their work.

Notable projects include the interactive, digitally controlled water curtains of the Digital Water Pavilion (2008) for the Zaragoza Expo, the Future Food District (2015) designed for the Milan Expo, a reimagined supermarket experience connecting consumers with food production and distribution using digital technologies, and Essential, the official torches for the Milano Cortina 2026: Winter Olympics and Paralympics.

The Importance of Taste

Far from algorithm-approved aesthetics, Italian design offers something that has become increasingly rare to come by these days: taste. In the world of fashion, Italy’s sartorial artistry lies in the intricate balance between architecture and ornament—a distinctive point of view shaped by cultural context, an unrestrained pursuit of beauty, and time-honored artistry—proving that the true measure of luxury is never about novelty, but about how it makes us feel.

Italian Fashion Design

Fashion is the jewel of Italy’s design crown. Rooted in medieval workshops and golden-age Renaissance courts, the fabric of Italian fashion unfolds a distinguishable identity synonymous with quality, craftsmanship, and manufacturing since its Florentine origins. While Italian fashion lost some of its luster to Louis XIV’s France, its revival in subsequent eras links its rise to global power with the mid-century ready-to-wear revolution.

Much like the rest of its modern practices, Italy’s ready-to-wear industry developed from a postwar need for high-end mass marketing. As consumers shifted between the exclusive and structured elegance of French haute-couture and the casual essence of American sportswear, Italian designers focused on producing clothing that incorporated the most appealing aspects of both: equally accessible and comfortable, as they were refined and tailored.

Italy has also been a huge exporter of fashion accessories and small leather goods since the early 20th century. Luxury textiles, shoes, and jewelry thrived prominently as fashion continued to evolve towards the signature boldness of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. Styled alongside radical bright colors, bold patterns, and unconventional materials, Italian accessories became symbols of excess and glamour that epitomized the look of the era.

By the turn of the 21st century, Italian style conquered the world in high-end sportswear collections, pioneering trends toward technology-inspired minimalism, detailed practicality, and sleek modernity. From tradition to innovation, “Made in Italy” excellence embodies a fusion of classic and contemporary elements pulling our enlightened attention back to lived-in, present tense.

Characteristics of Italian Fashion

Artisanal craftsmanship in contemporary design

In Italy, craft informs a practice that respects its story as much as its form. Besides its economic value as the third biggest industry in the nation, Italian fashion is designed to be worn.

The importance of knowledge and expertise turns out to be the country’s main market differentiator poisoning itself as a strategic hotbed for talent development, regional manufacturing, and distribution.

Istituto Marangoni, Polimoda, Istituto Europeo di Design (IED), Accademia Costume & Moda, Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti (NABA), and Politecnico di Milano are highly regarded institutions with a strong art, fashion, business, and design programs.

Regional manufacturing recognizes Tuscany for its textile industry, wool production, and traditional vegetable tanning techniques, Emilia-Romagna for knitwear and womenswear, Lombardy for its silk and luxury products, and Naples for menswear excellence, among many others.

Alongside hosting its bi-annual fashion week, Milan’s Quadrilatero della Moda is a renowned global epicenter for luxury fashion and design, while Florence boasts Via de’ Tornabuoni, a street blending high fashion with artisanal craftsmanship in a vibrant atmosphere, and Pitti Uomo, a collection of fashion industry events for men’s clothing and accessory collections.

Sprezzatura, or the art of doing less but better. Characterized by high-quality materials (like silk, cashmere, and fine leather) and impeccable tailoring, Italian style is widely anchored in the concept of ‘sprezzatura,’ or the art of making something difficult appear effortless.

This idea of nonchalant confidence strikes the perfect balance of considered attention to detail and effortless, casual grace. As such, Italian sprezzatura prioritizes well-made, durable pieces over fast fashion, impeccable tailoring over fleeting trends, and emphasizes the importance of well-chosen accessories to elevate an outfit.

Timeless elegance takes hold

The term may sound like taken out of any fashion brand’s playbook, but the idea of timeless elegance in which the past, present, and future can naturally co-exist, situates Italian design as highly aspirational.

Even with the resurgence of the vibrant Italian Maximalist movement with its abundance of color, patterns, and textures, the region’s focus on beautiful functionality preserves its relevance in the global fashion landscape.

Who’s Who in Italian Fashion

For many, Giovanni Battista Giorgini is considered the father of Italian fashion. In 1952 Giorgini organized the ‘First Italian High Fashion Show’ at Villa Torrigiani, his private residence in Florence. The show attracted prominent American buyers and journalists, and marked the nation’s catwalk debut to international acclaim—a pivotal moment in the history of the ‘Made in Italy’ brand.

Highly influential and innovative, Elsa Schiaparelli is known for her surrealist-inspired creations that blend French and Italian aesthetics. The Italian-born, Paris-based fashion designer was a revolutionary figure in 20th-century fashion.

Through bold use of color and unconventional designs, Schiaparelli challenged traditional notions of beauty and elegance, often collaborating with prominent surrealist artists, like Salvador Dalí and Jean Cocteau, and incorporating their ideas into her work. American designer Daniel Roseberry, has served as artistic director of Maison Schiaparelli since 2019.

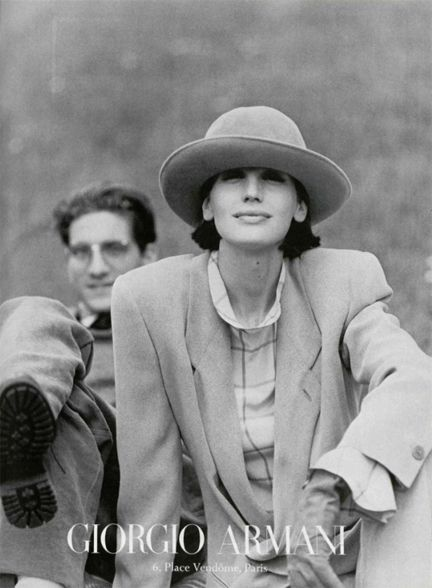

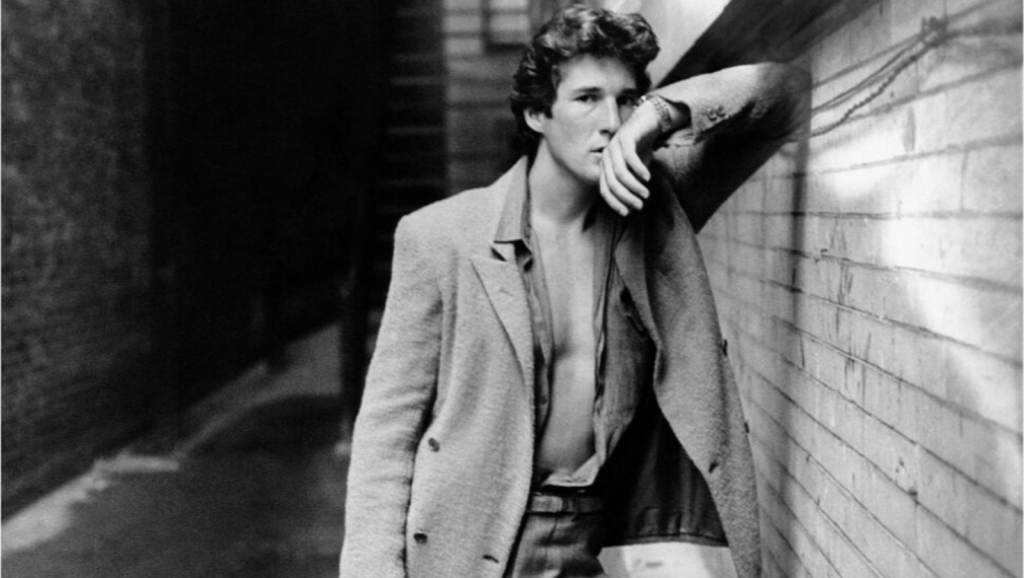

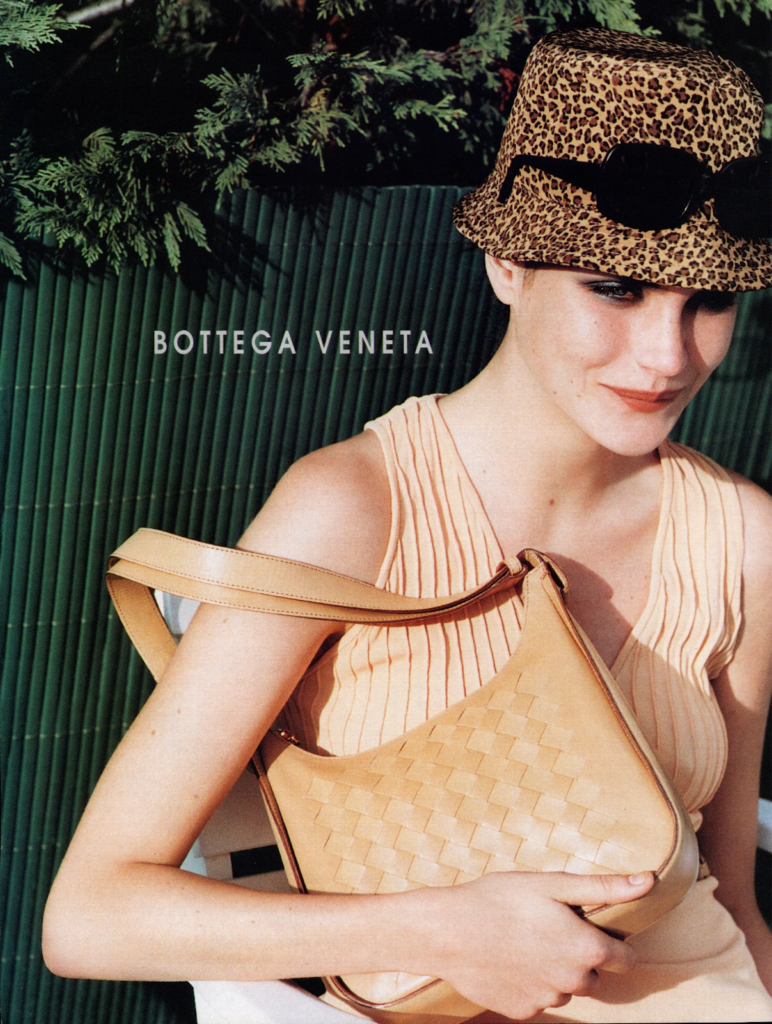

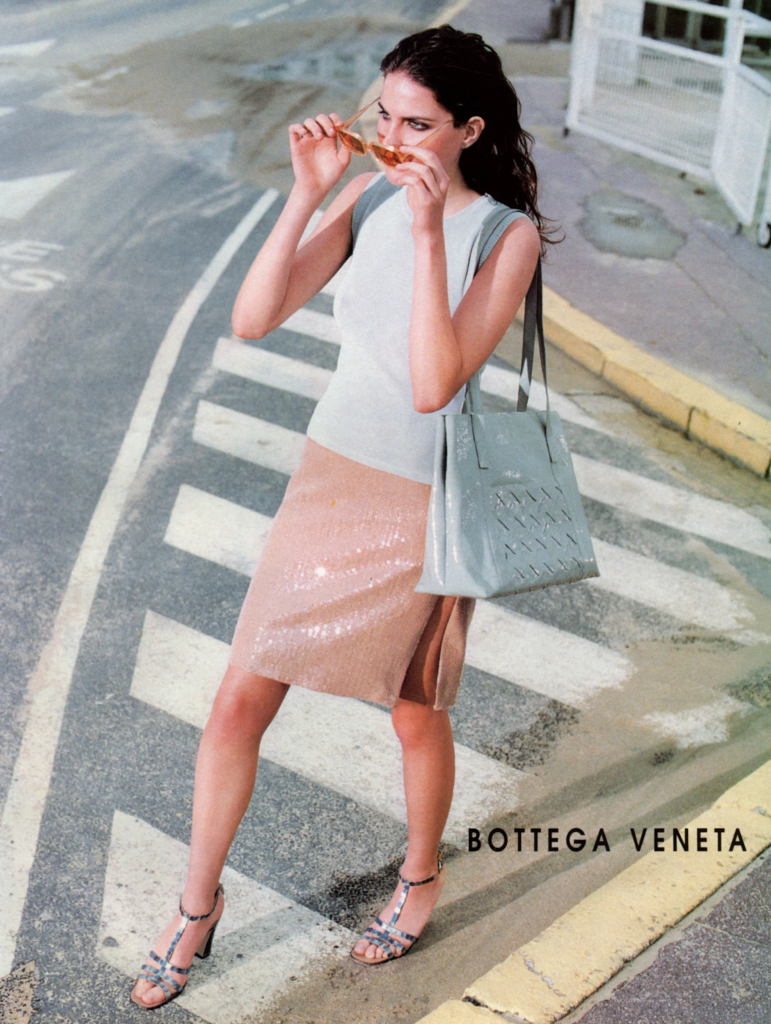

Keeping up with the semplicità ed eleganza of the Giants of Italian Fashion, let’s look at the traits that turned them into contemporary global powerhouses. For understated elegance, look no further than Giorgio Armani’s sophisticated power dressing, Loro Piana’s understated luxury, Max Mara’s wardrobe mainstays, Salvatore Ferragamo’s sharp tailoring, and Bottega Veneta’s signature intrecciato leathercraft.

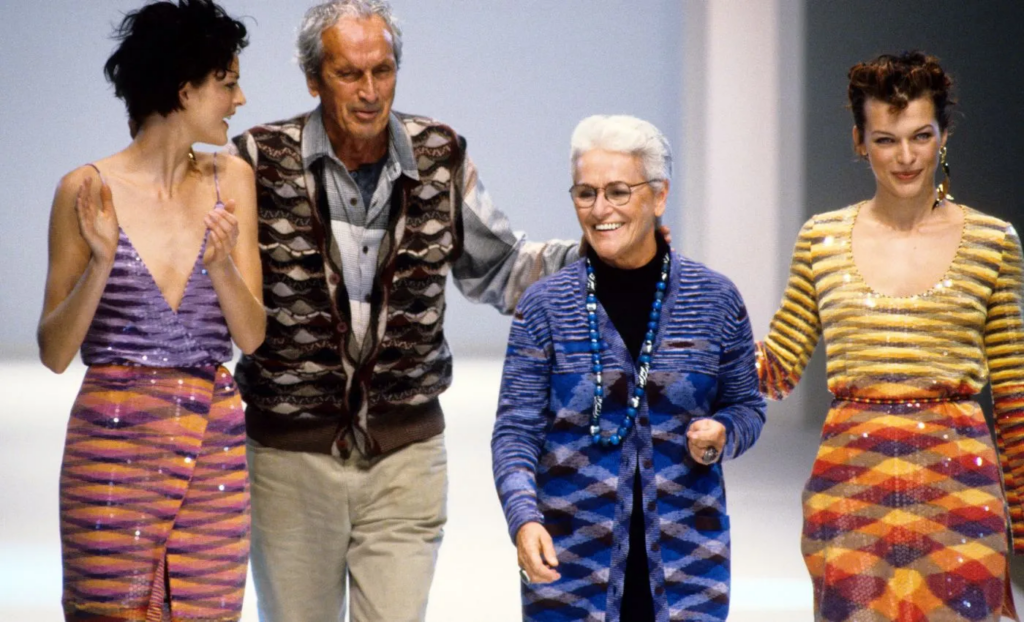

If romance moves you, turn to Valentino’s timeless ready-to-wear and alta-moda collections, or run to Versace for boldness and baroque prints. Heritage calls on Gucci’s equestrian origins, Fendi’s fur workshops, Brunello Cucinelli’s knitwear and Dolce & Gabbana’s Sicilian roots, while Missoni’s colored lamé yarns tie artisanal Italian excellence and a unique style together.

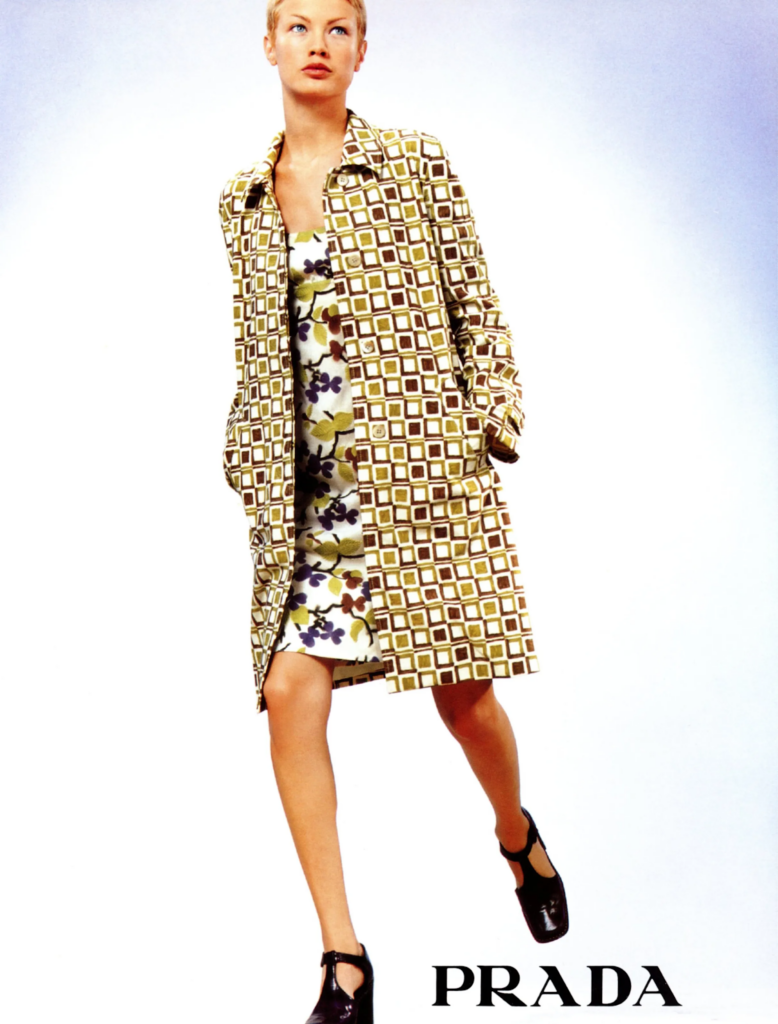

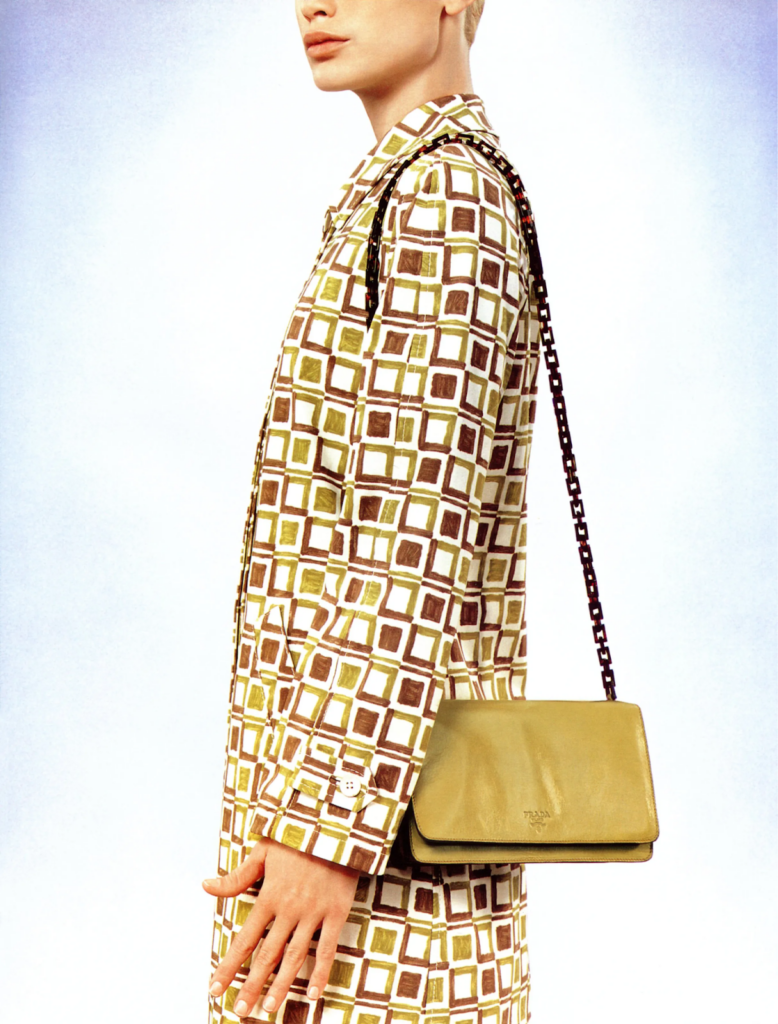

Retro jet-set glamour makes up the DNA of Etro’s high-end bohemian spirit and Roberto Cavalli exotic flair. Or, switch between Prada’s “ugly-chic,” intellectual (and subtly avant-garde) minimalism, Marni’s colorful eclecticism, and Moschino’s playful, irreverent creations for a mid-week pick-me-up.

Franca Sozzani, the late editor-in-chief of Vogue Italia, was known for her sharp intellect, keen eye, and innovative approach to fashion journalism, transforming the magazine into a platform for social commentary.

Her sister, Carla Sozzani, founded Milan-based 10 Corso Como in 1990, starting as an art gallery and bookshop, with its retail space opening a year later. 10 Corso Como is widely recognized as the world’s first modern concept store, followed by Excelsior Milano (2011) and Casa t r i p l e f (2020), influencing global retail trends and continuing the legacy of pioneering LUISAVIAROMA (1929).

In 2016, Carla Sozzani, Kris Ruhs, and Sara Sozzani Maino founded Fondazione Sozzani, dedicated to promoting contemporary cultural and artistic activity through various programs and events, just as its predecessor Galleria Carla Sozzani.

The Ones to Watch

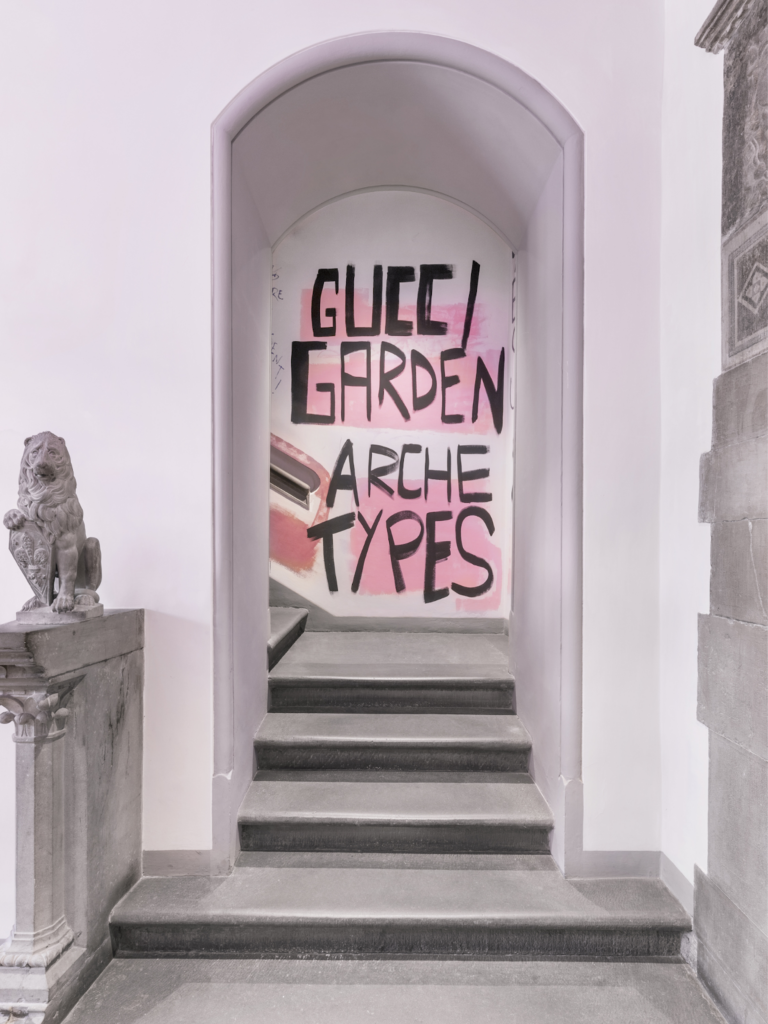

Never one to follow trends, Alessandro Michele imposes his unique blend of the ugly and the beautiful into his ornate creations, from fashion and high jewelry to retail interiors and exhibitions.

Known for his recognizable geek-chic style, maximalist tendencies, nostalgic vintage inspirations, and gender fluidity, Michele combines pattern, texture, and color in his more is more approach to classic Italian tailoring.

The former Gucci creative director, Michele succeeded Valentino’s longtime creative director, Pierpaolo Piccioli, in 2024. Among his extensive range of projects, Michele debuted industry-defining collaborations in the luxury space, such as Gucci x The North Face (2021), focusing on eco-friendly practices, and the Hacker Project with Balenciaga (2021), a co-branded collection of apparel, accessories, and footwear.

Highlighting his curatorial vision is the multifaceted space Gucci Garden in Florence, conceived by Michele, reimagines the brand’s history and creative vision through dynamic and immersive experiences.

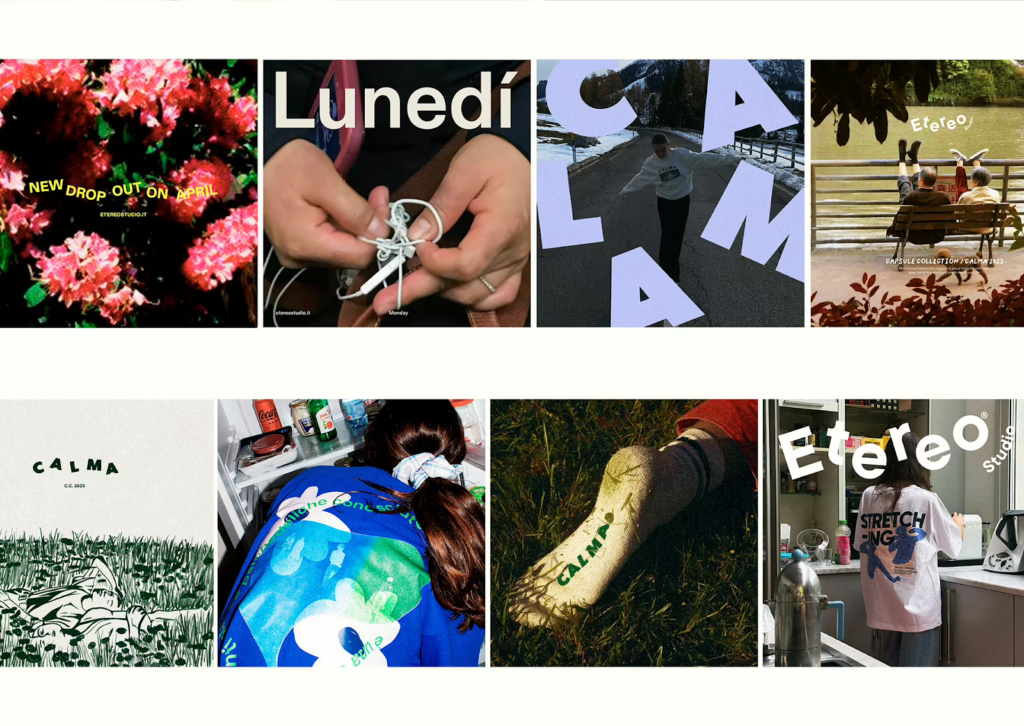

Sunnei is a contemporary Italian fashion brand founded in 2014 by Loris Messina and Simone Rizzo. The duo’s menswear, womenswear and accessories collections are characterized by playful, oversized silhouettes, and unexpected fabric combinations that emphasize the versatility and practicality in their designs.

Sunnei is known for its inventive and playful show formats, from crowd-surfing to real-time collection ratings. Their FW24 show exposed the adaptability of their garments and patterned scenography by CC-Tapis at the studio’s Milan headquarters. Most recently, at their SS25 show, the brand commemorated their 10th year anniversary in an exploration of time and the idea of “10 feels like 100” embodied by older models.

Veronica Leoni is an Italian fashion designer who has previously worked at Jil Sander, Céline (during Phoebe Philo’s tenure), Moncler, and The Row. Her solo project, Quira, earned her a finalist spot in the 2023 edition of the coveted LVMH Prize for Young Designers.

Anchored in streamlined minimalism, bold style, and playful elegance, Leoni’s Quira brings sentimental value to clothing in meticulous detail and intricate motifs that reflect the kind of fashion that contemporary women want to wear.

Her philosophy is sophisticated with a tinge of sensuality and an impeccable taste for tailoring. Her most recent appointment as Calvin Klein Collection’s creative director brought back the stripped-back minimalism of the label’s 1990s glory.

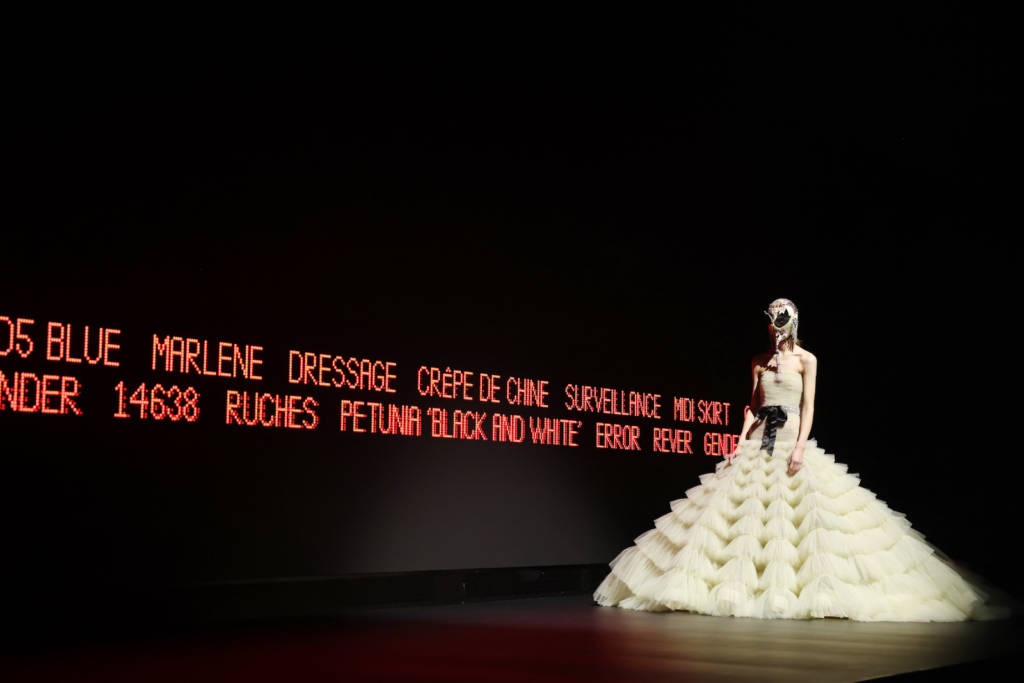

Italian fashion designer, Pierpaolo Piccioli, is known for his masterful draping, voluminous silhouettes, and use of fabrics to create striking shapes and movement. Serving as creative director of Valentino between 2008 and 2024, Piccioli expanded the house’s color palette with his Fall Winter 2022 collection debuting “Pink PP,” his bespoke bright color mix of fuschia and deep purple, adding a contemporary hue to the brand’s signature red.

In 2025, he was appointed Balenciaga’s new creative director, expected to debut the house’s Spring Summer 2026 collection.

Moncler is a luxury fashion brand known for its high-quality down jackets and outerwear. Initially from a small mountain village near Grenoble, France, the brand was acquired by Italian businessman, Remo Ruffini, in 2003.

Rufini is credited with transforming the label by strategically introducing new lines, like Moncler Gamme Rouge and Gamme Bleu, led by renowned fashion designers shifting Moncler from purely functional outerwear to high-end fashion.

The project Moncler Genius was introduced in 2018 which each year invites a selection of designers, such as Pierpaolo Piccioli, Hiroshi Fujiwara, Rick Owens, JW Anderson, and Simone Rocha (among others) to create their own interpretations of the down jacket. The project has expanded beyond fashion to include partnerships with artists, musicians, and other talent in different creative fields.