Many countries have played a pivotal role in shaping global artistic expressions, but only one has left an indelible mark in the contemporary world of design thanks to its distinct contextual approach to the art of craftsmanship.

In Germany, design is closely tied to the history of industrialization and social reform. Benchmarked by principles of innovation, functionality, minimalism and cleanliness, German design is embedded with the values of efficiency, precise craftsmanship with a focused dedication to quality, sustainability and environmental protection.

Let’s explore!

1. Innovation: The catalyst of German design

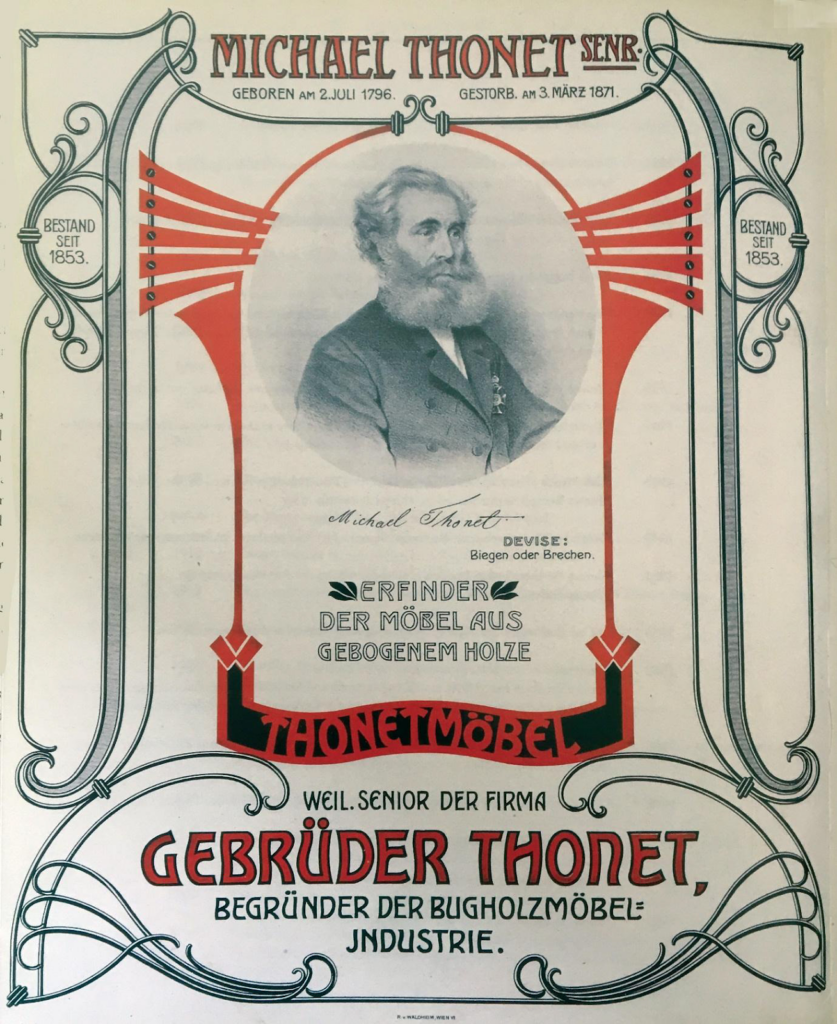

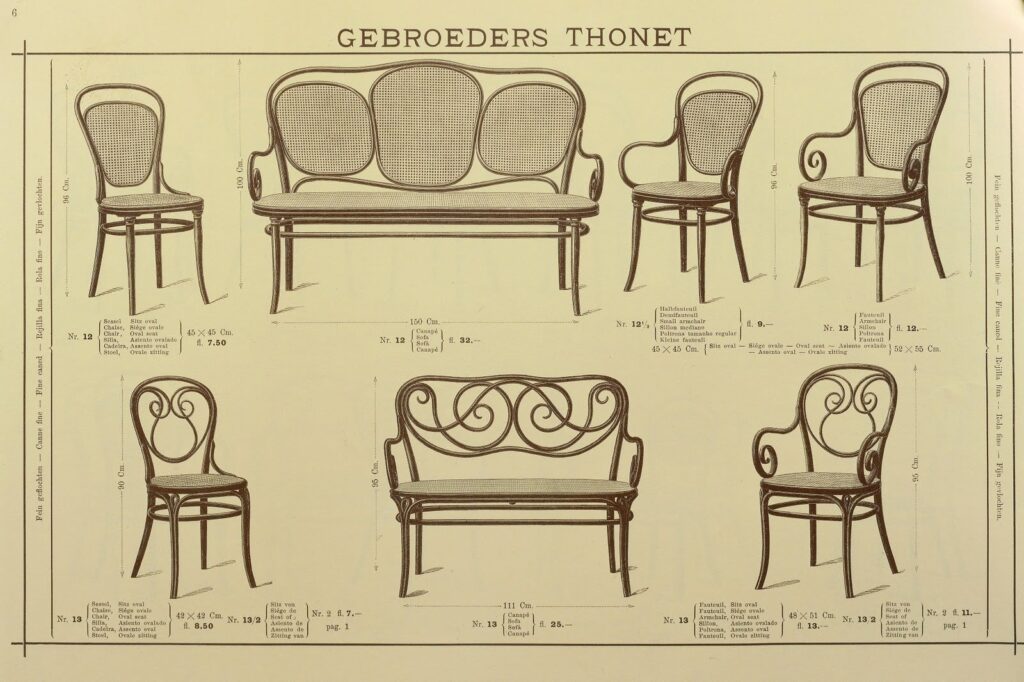

The story of German design begins with the Industrial Revolution of the 19th century. Its key starting point was Michael Thonet’s 1859 international breakthrough with Chair No.14—today 214—the most commercially successful chair ever produced in the history of furniture.

The German-Austrian cabinet maker wanted to create a chair that could be both good-looking and inexpensive—an idea that required over twenty years to perfect and made possible by the technological innovation of the steam engine.

As the driving force behind industrialization, steam found many uses in a variety of industries, particularly initiating technological advancements in manufacturing.

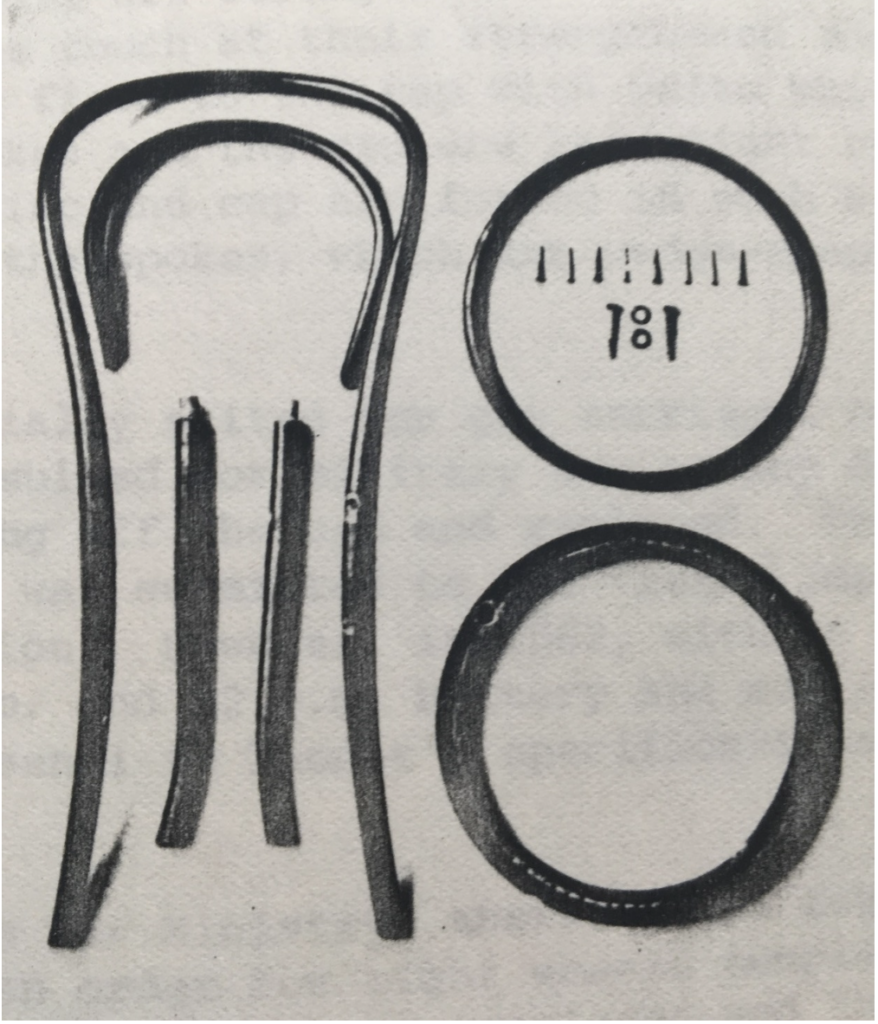

Composed of six hand-finished pieces of steam-bent beech wood, ten screws and two nuts, Thonet’s No.14 delivered the earliest example of mass production that forever changed the trajectory of craftsmanship by replacing workshops with machine-led factories.

No.14 denoted a premium feel in both design and materiality that referenced traditional German design vernacular: elegant utility, clean lines and geometric shapes. A curve-bent backrest, a round seat and subtly flared legs spoke of its technical innovation, sustainability, and aesthetic longevity.

Its genius distribution model also established the earliest beginnings of modern furniture: thirty-six disassembled No.14 chairs could be easily packed into a one-cubic-meter box and shipped to customers around the world along with instructions that facilitated on-site assembly.

Nurholz, Michael Mahle

Michael Mahle’s nurholz project is similar to Thonet’s modular principle. Mahle employs digital manufacturing techniques, such as CNC milling, in combination with traditional woodworking in his expandable and repairable furniture designs built on one another with adaptable individual elements.

At the core is a rotating element that allows for easy assembly and disassembly: Mahle’s patented glue- and metal-free wood connection. Creating consistently circular concepts, Nurholz facilitates mass customization marking an exemplary expression of eco-effectiveness and German precision.

Formstelle, Claudia Kleine & Jörg Kürschner

The Munich-based Formstelle was founded in 2001 by Claudia Kleine and Jörg Kürschner. Their award-winning work includes the 808 for Thonet, a re-contextualization of the classic wingback chair, and Morph for Zeitraum, a set of wooden chairs.

Kleine and Kurschner’s discipline involves wood in combination with contrasting materials such as metals and stone, developing concepts, spaces and products that are characterized by authenticity, innovation, and a strong enthusiasm for experimentation.

Poise Floor, Robert Dabi

Driven by the interplay of form and function, Robert Dabi has a special eye for detail and a knack for visual storytelling. The interdisciplinary and versatile multi-hyphenate based in Nuremberg is known for combining aesthetics with usability using additive and traditional manufacturing.

Poise Floor is a minimal and flexible floor lamp consisting of a bent frame that holds a big spotless LED ring allowing it to be moved to any position, each creating a unique light appearance. Dabi’s design was awarded the 2021 Golden A’Design Award.

2. Functionality: From Bauhaus to Bold

One of the most distinctive characteristics of German design culture is its emphasis on simple, problem-solving concepts. In the wake of World War I and the Industrial Revolution of the 19th century, a new radical school of art and design emerged.

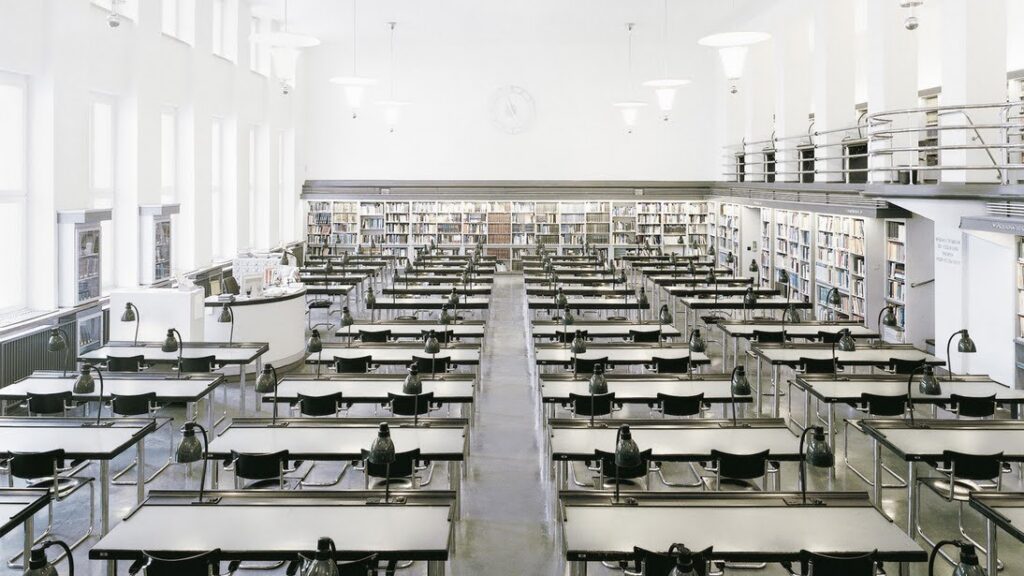

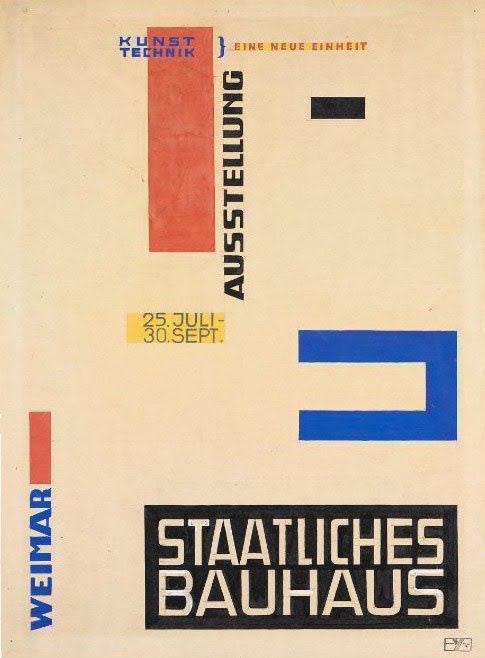

Bauhaus at its core was a holistic school of thought that broke the constraints of tradition and bridged the gap between art, design, and commerce. Color theory, geometry, simplicity, functionality, asymmetry, and modernity were at the forefront of its philosophy influenced by the avant-garde movements of the time: Futurism, Constructivism, Cubism, Expressionism, and Gestalt psychological theory.

The institution took advantage of machine production to resolve problems of functional design. Led by visionary architects, designers, and artists, Bauhaus students were encouraged to meet design requirements for factories’ mass production with a “form follows function” philosophy that marked a seismic shift from the ornate and often impractical designs of the past.

Mart Stam’s S 33, the first ever cantilever chair, Mies van der Rohe’s S 533 and Marcel Breuer’s cantilever classics, the S 32 and the S 64.

Bauhaus produced a visual language that was accessible, purposeful and aesthetically pleasing with a deep understanding that greatness didn’t come from maximizing every detail, but from processing details into something consumable.

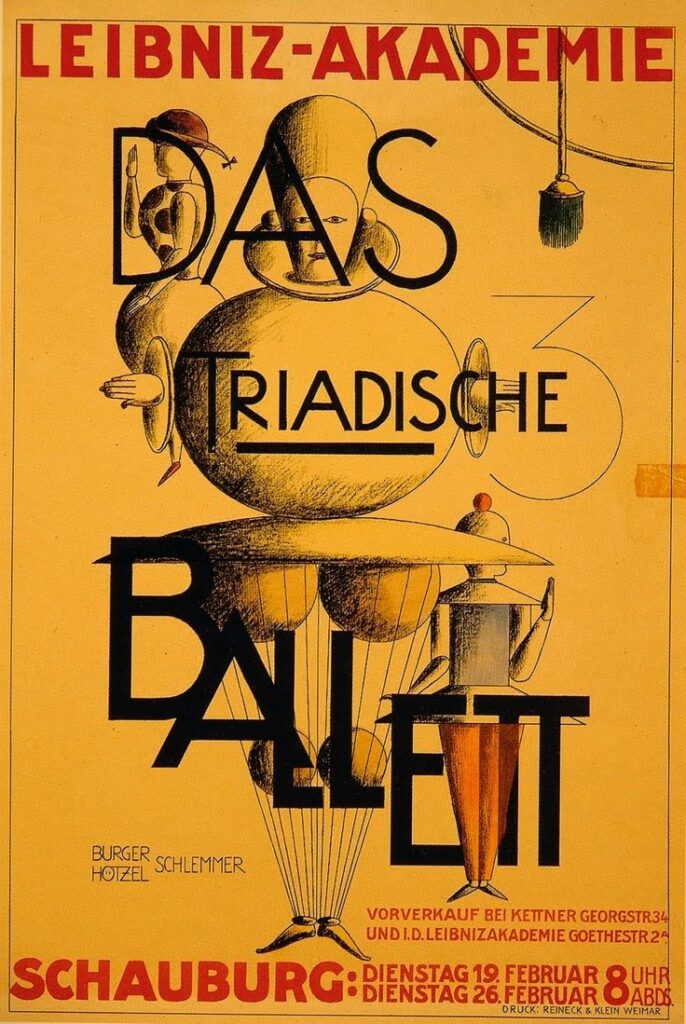

The ballet became the most widely performed avant-garde artistic dance and while Schlemmer was at the Bauhaus from 1921 to 1929,

the ballet toured, helping to spread the ethos of the Bauhaus.

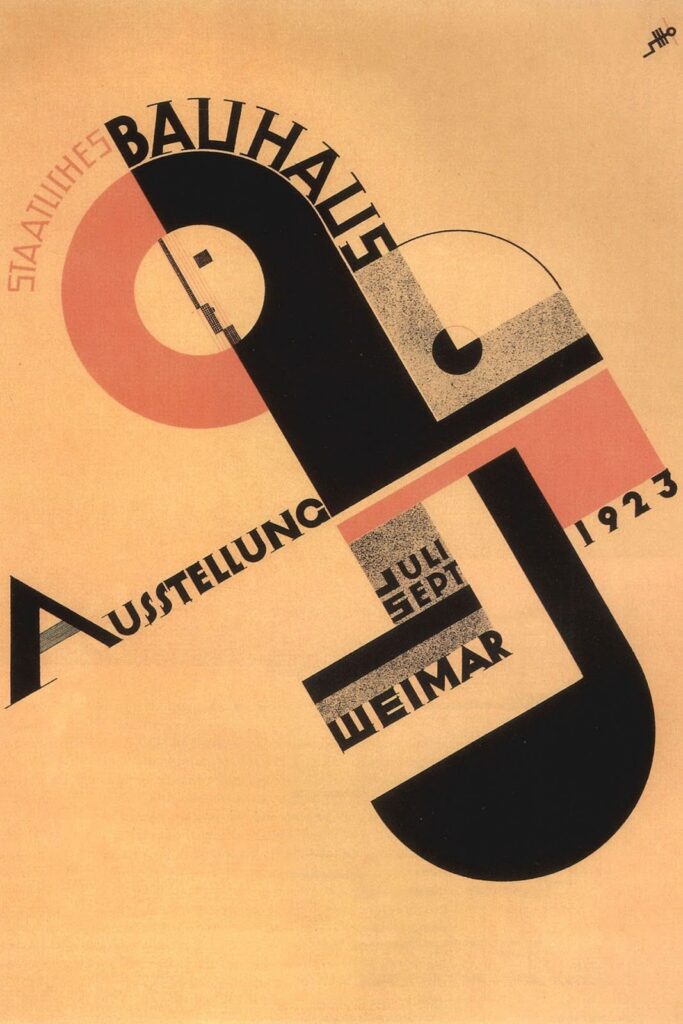

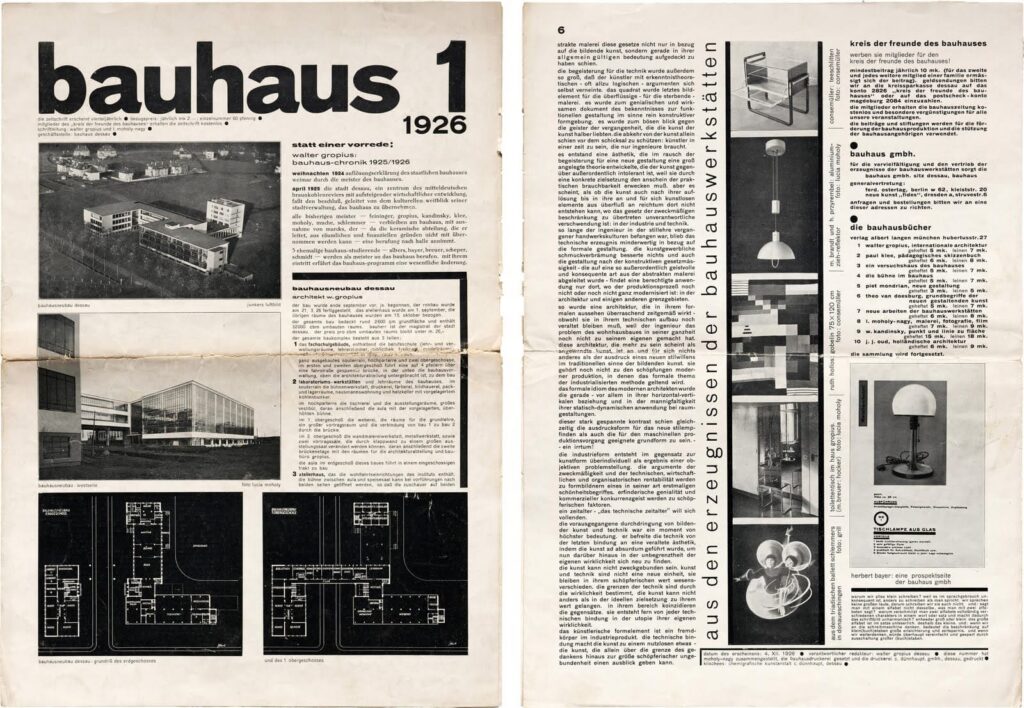

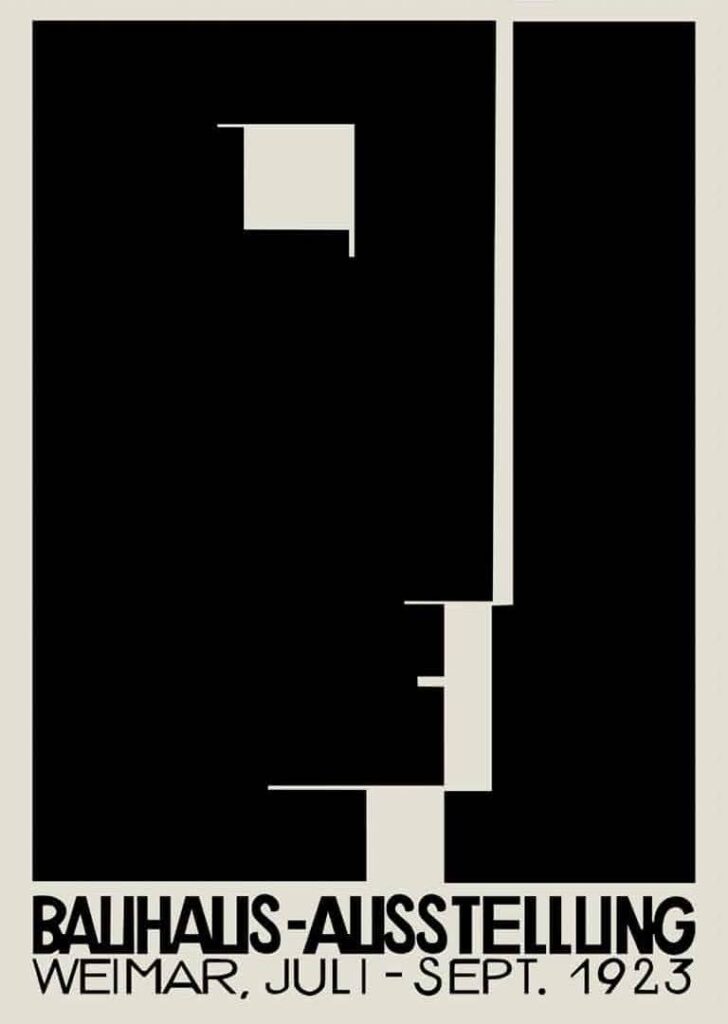

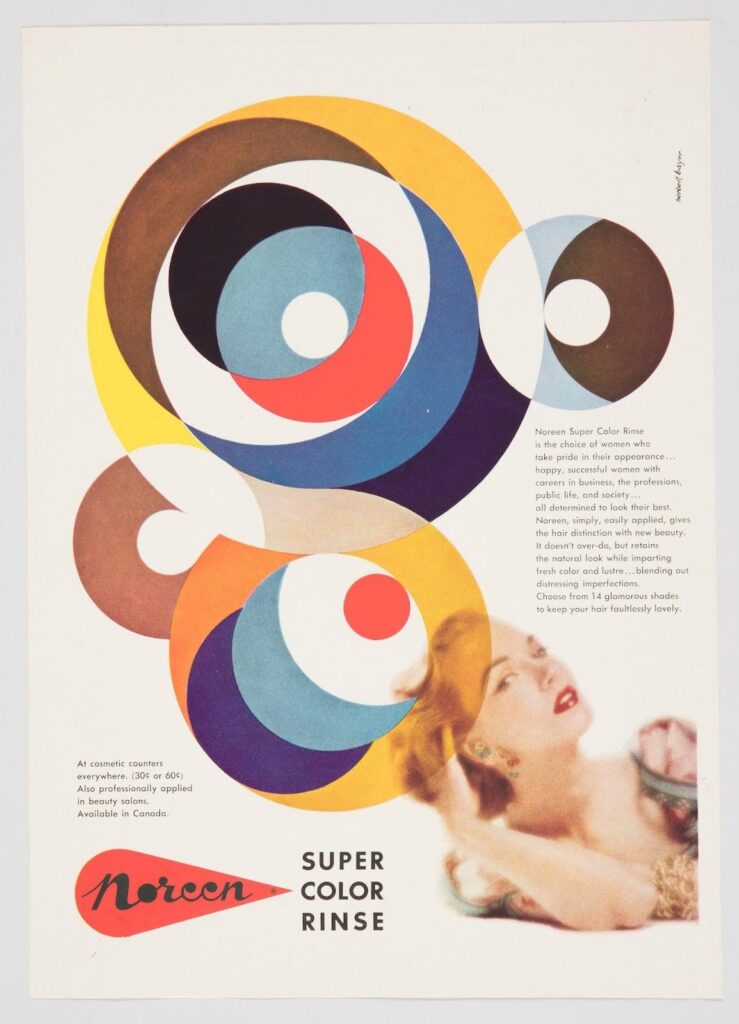

1923 Bauhaus Exhibition Poster, Herbert Bayer

Bauhaus’ design principles became a cornerstone of modern design. From the sleek lines of our Apple devices to the minimalist beauty of today’s graphic design are all remnants of its legacy.

Featuring the original Bauhaus logo designed by Oskar Schlemmer in 1922.

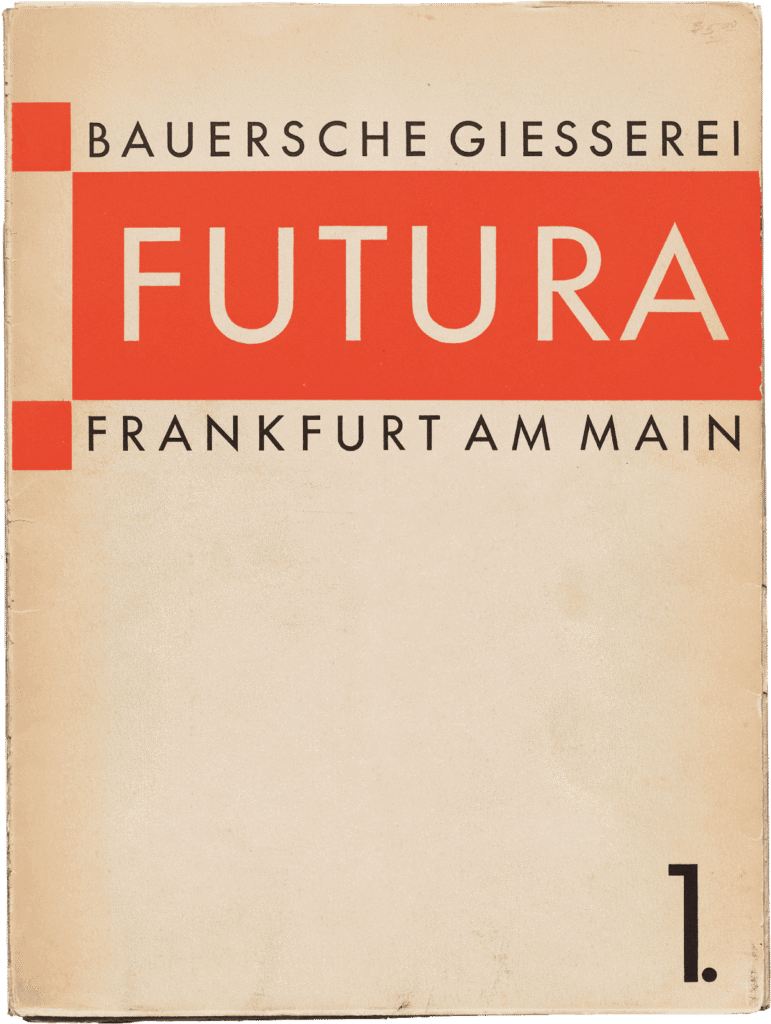

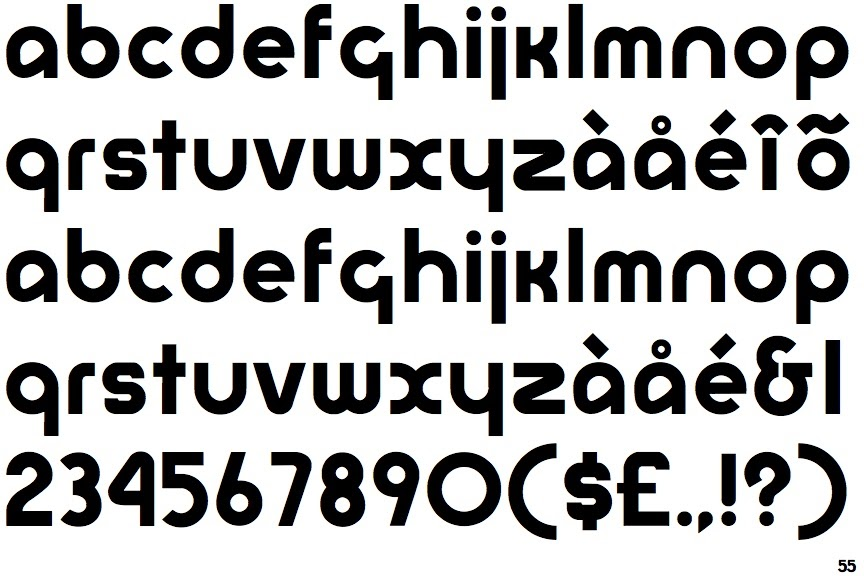

Bauhaus polymath Herbert Bayer championed the use of sans-serif typefaces and asymmetrical layouts in his work, finding success in graphic design and advertising for fashion and textiles, as well as posters, brochures and official commissions for the government.

Known for its bold type and geometric shapes, Bayer’s Bauhaus exhibition poster of 1923 remains an iconic symbol of the movement.

in an effort to create a minimalist aesthetic that is vibrant and colorful.

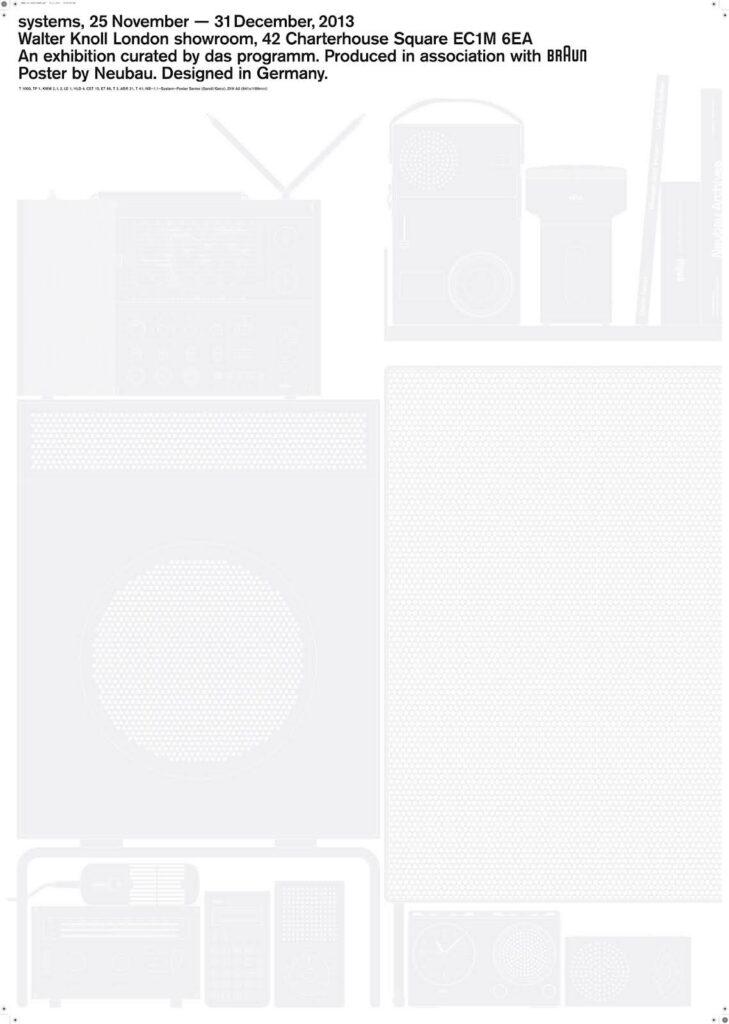

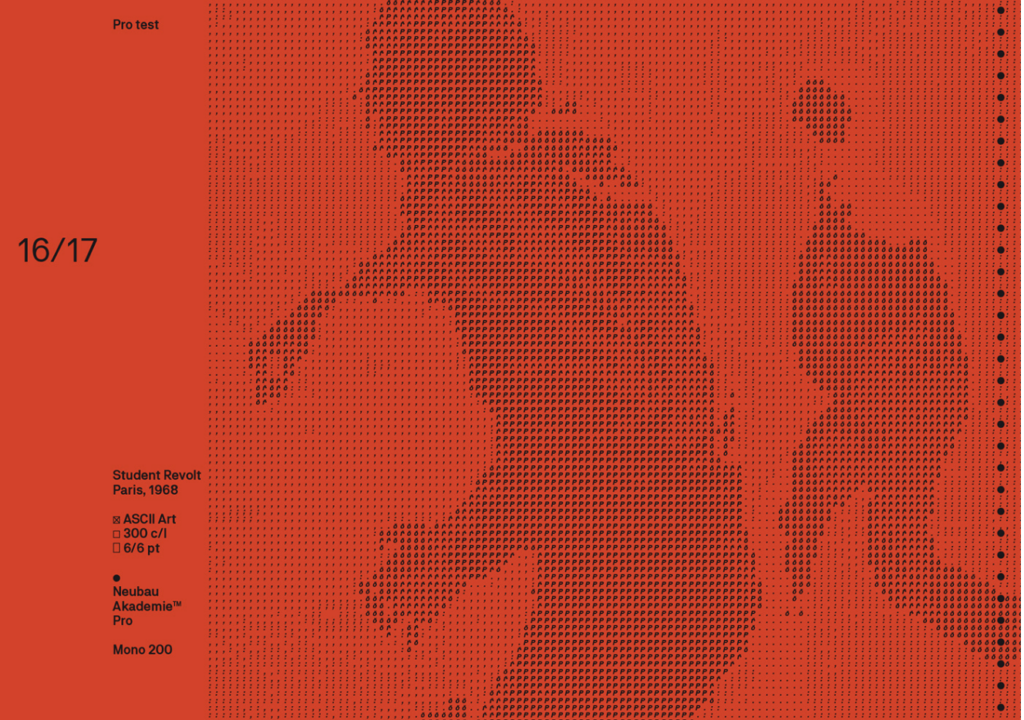

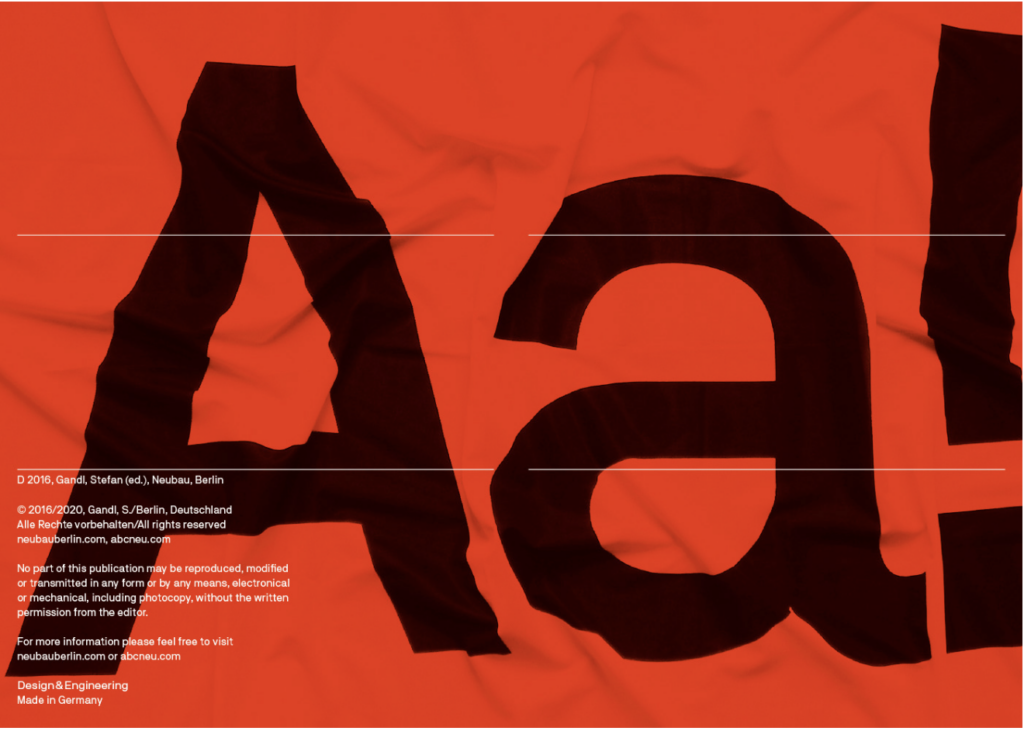

NB ASR B, Neubau

Founded in Berlin in 2001 by Stefan Gandl, Neubau is an independent design studio that develops print, screen and space design and typography.

The studio’s permanent showroom and archive space, NB ASR B (Neubau Archive Showroom Berlin), guides visitors through a kinetic journey of installations, from modular projections to prints and previously unseen projects by the acclaimed collective.

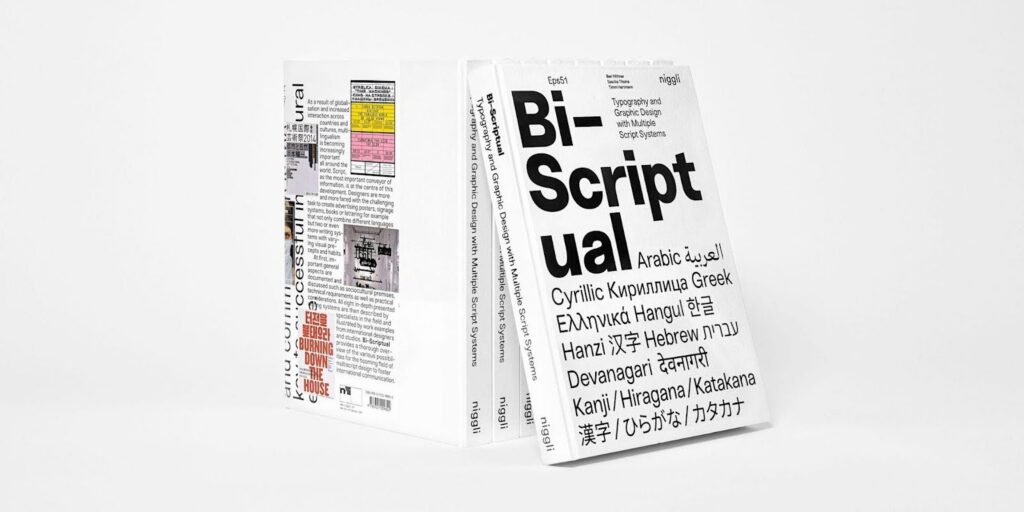

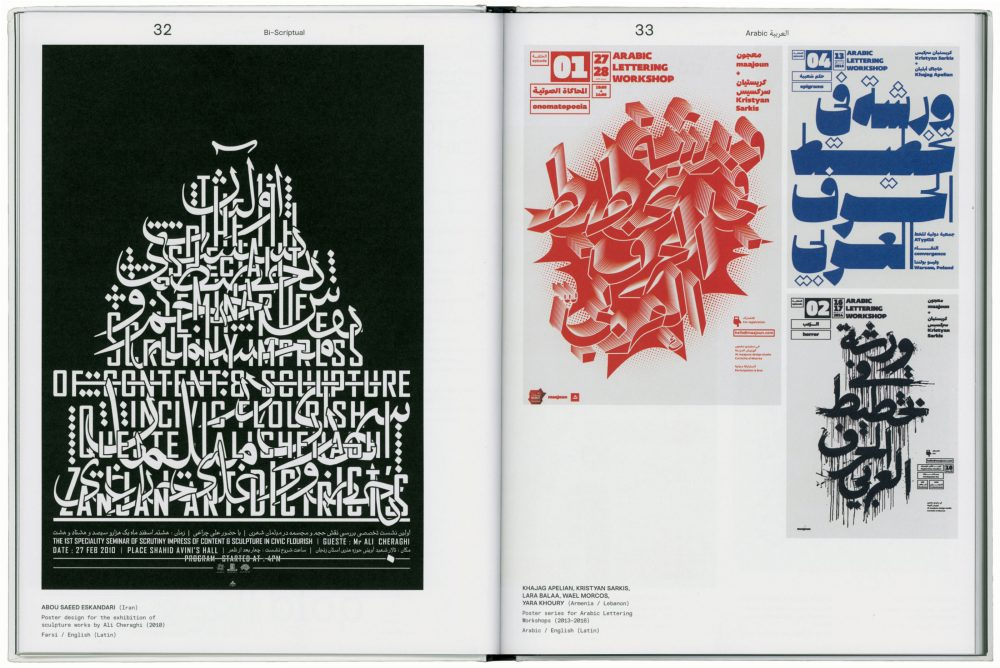

Bi-Scriptual, Eps51

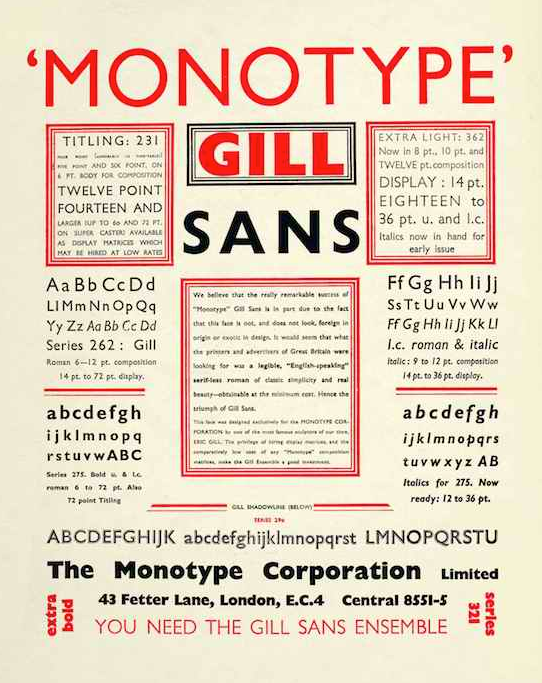

Germany’s harmonious fusion of artistic sensibility and industrial precision of the 20th century paved the way for a graphic design style that was not only visually striking but also highly functional.

Today, Berlin-based graphic studio, Eps51, focuses its identity, print, motion, and web design practice around multiscript design and typography. The studio’s Bi-Scriptual book combines different languages, two or more writing systems with varying visual systems, providing a thorough overview of intercultural exchange as a result of globalization and multilingualism.

Bi-Scriptual presents eight writing systems described by specialists in the field and illustrated in typographical works from over 120 international designers and studios, visually communicating socio-cultural contexts and political cues.

3. Minimalism & Cleanliness: What makes design good?

After the division of Germany in 1949, design and everyday culture went their separate ways. On each side of the border post-war design presented a panoramic view of ideological and aesthetic differences: plastic and loud colors in a socialist East was pitted against cool functionalism of the West.

But before the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, an independent strand of design emerged in the country.

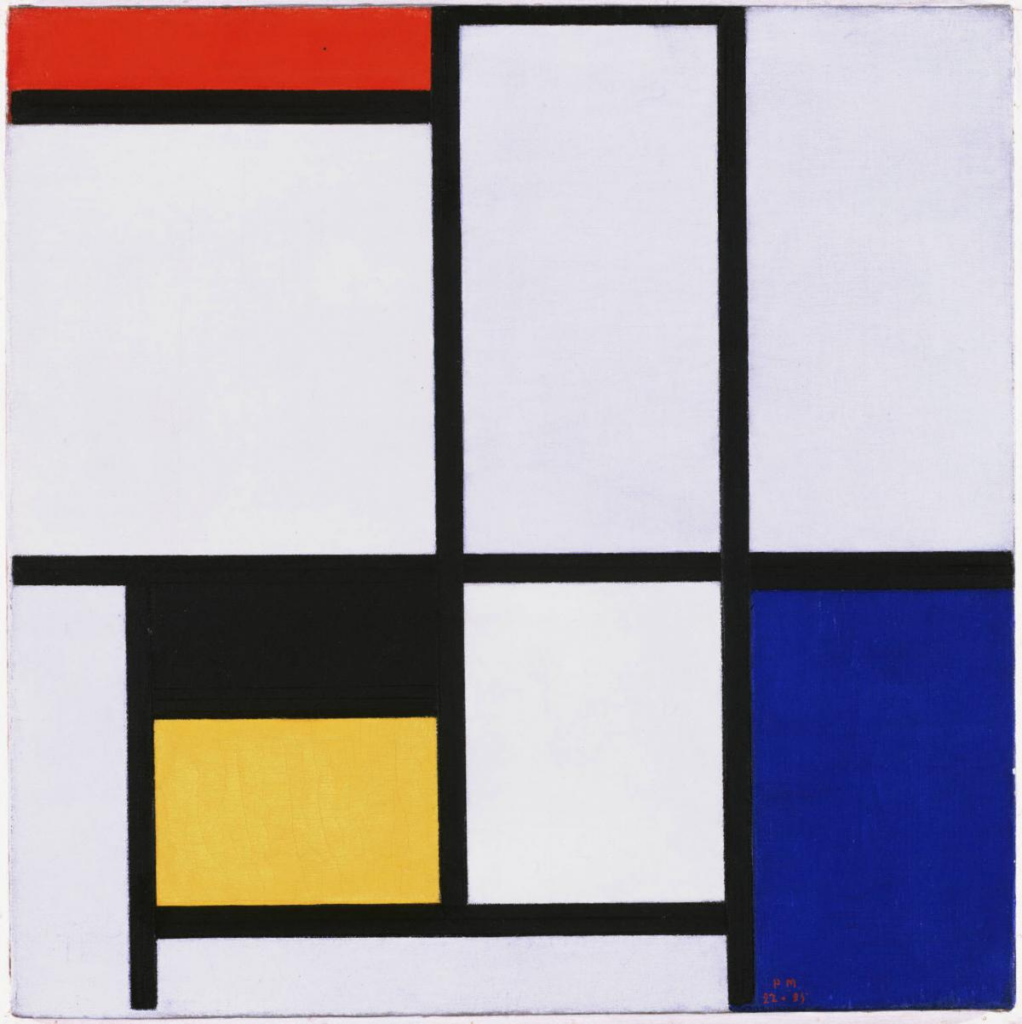

Minimalism developed in 1960s Germany in response to Concrete Art’s exploration of abstraction and Zero avant-garde’s focus on materiality, light and space. As the name suggests, minimalism kept form and content to only the necessary essentials to convey a message.

German minimalism favored the use of radically clean gestures of subjectivity and rationality to reflect the intended purpose and essential functions of an object. Simplicity led to efficiency employing clean lines, geometric shapes, and uncluttered compositions that underscored a sense of modernity and advancement.

As the cornerstones of German contemporary design, minimalism and cleanliness resonated in the realms of art, product, architecture, fashion, and beyond.

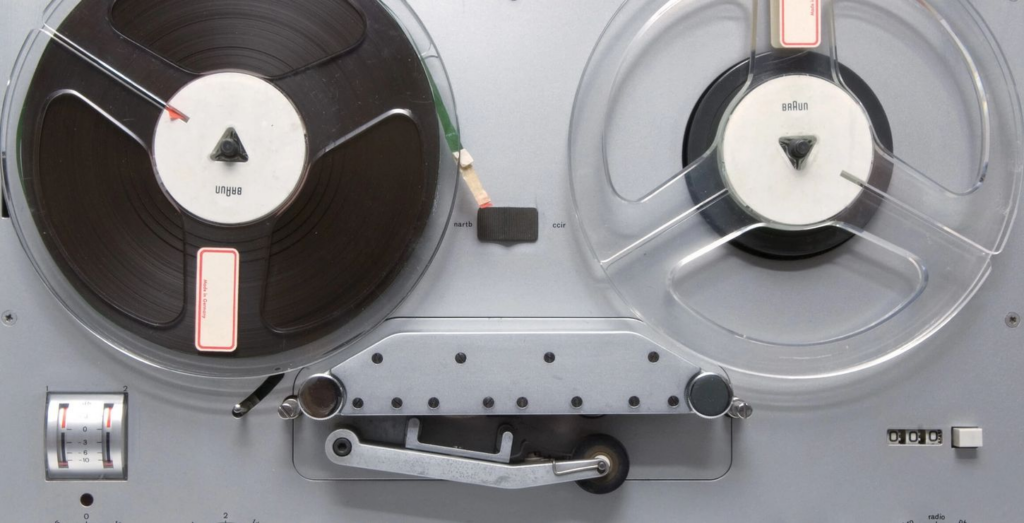

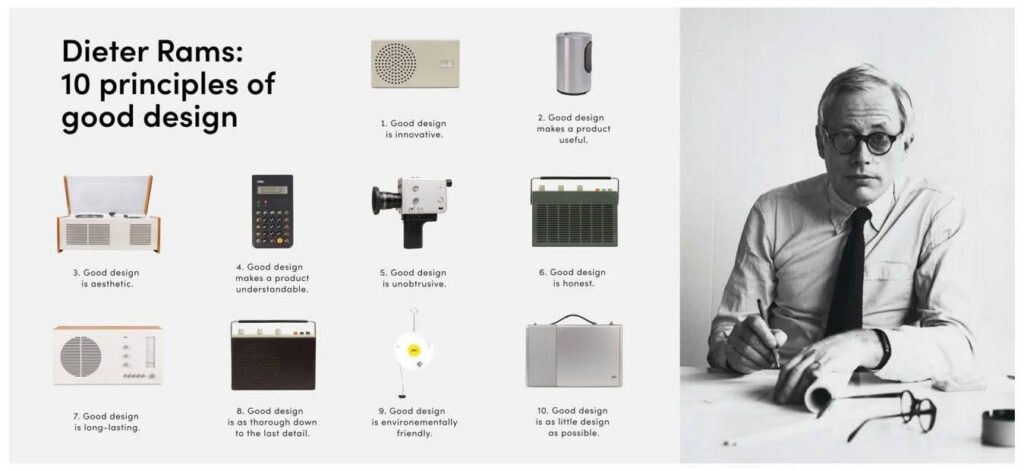

Between 1961 and 1995, industrial designer Dieter Rams developed a longstanding partnership with Braun, the German consumer goods manufacturer as its head of design. Rams created some of the most prominent and enduring product designs in the latter half of the 20th century taking inspiration from the world around him.

His work championed clean lines, timeless sleek profiles, functional layouts, user-friendly simplicity, and accessible, cutting-edge technology.

For Rams German design standards are set by “the reduction to essentials without eliminating the poetry.” Recognizing the importance of actual quality over perceived quality he engineered the now-iconic set of doctrines for his “less but better” design philosophy better known as ‘Dieter Rams’ 10 principles of good design’ which keep inspiring designers across the world today.

Maria, Königin des Friedens, Gottfried Böhm

The work of architect Gottfried Böhm led by the conscious interaction of architecture and urban environments. His structures, mostly in molded concrete and later steel and glass, blend the old with the new emphasized by connections of form, material, and color.

Böhm’s most influential and recognized building is the monumental Maria, Königin des Friedens in Neviges.

Standing like a jagged concrete mountain and punctuated with windows of brilliantly colored stained glass, the pilgrimage church towers against its great medieval and Baroque predecessors reflecting both post-war austerity and mysterious visual suspense.

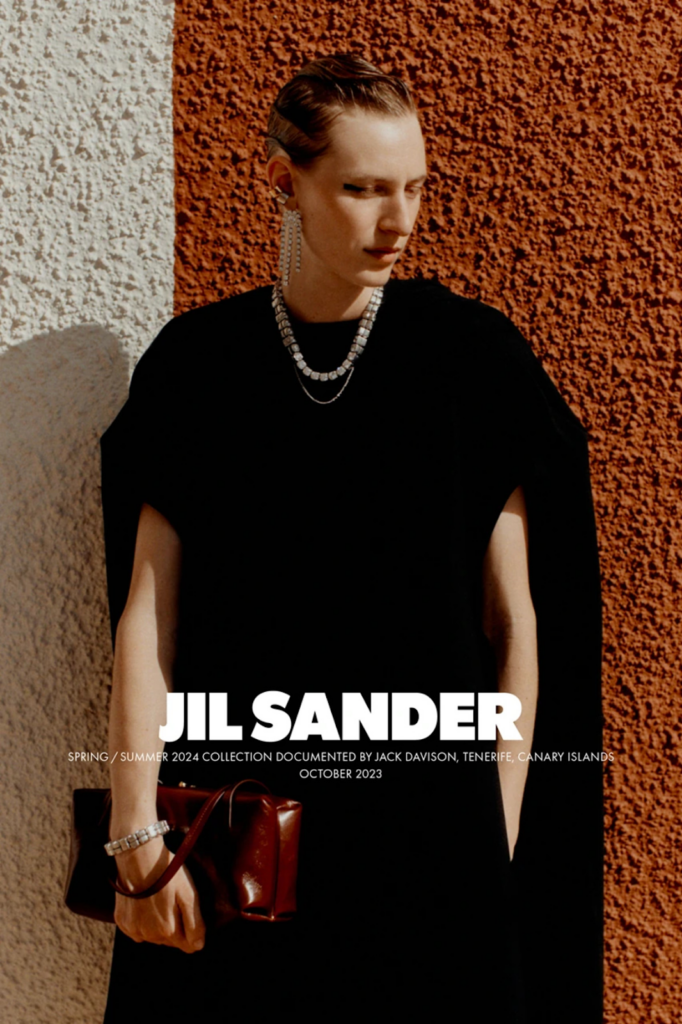

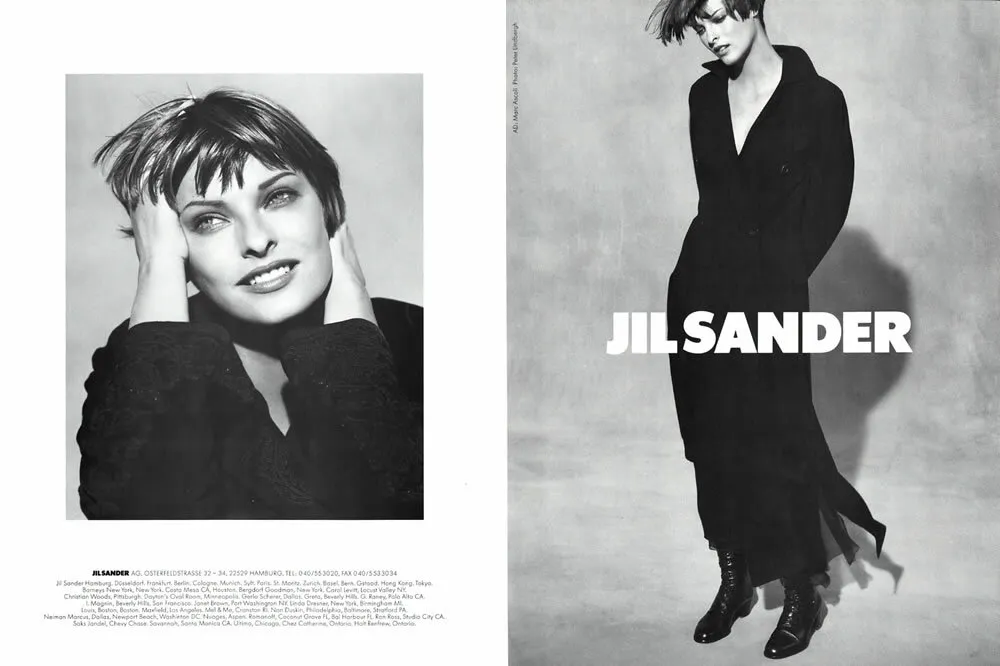

Jil Sander, Lucie and Luke Meier

German fashion designer Jil Sander established her eponymous house in 1968 in Hamburg. Known as the Queen of Less, Sander’s uncompromisingly clean-cut take on wardrobe staples put intent into action which assured the house’s reputation as a standard bearer for modern design. Her approach ushered a new take on femininity based on the enduring vision of quality and clean lines in the making of luxurious understated clothing and accessories.

Innovative materials and exceptional craftsmanship earned Sander international fame and expansion between the 1970s and 1990s due to her brand’s characteristic excellence and attention to detail.

Sander’s influence on minimalist fashion continues with co-creative directors Lucie and Luke Meier’s commitment to simplicity and functionality in fashion design.